I – II – III – IV – V – VI – VII – VIII – IX – X – XI – XII – XIII – XIV – XV – XVI – XVII – XVIII – XIX – XX – XXI – XXII – XXIII – XXIV – XXV – XXVI – XXVII – XXVIII – XXIX – XXX – XXXI – XXXII – XXXIII – XXXIV – XXXV – XXXVI – XXXVII – XXXVIII – XXXIX – XL – XLI – XLII – XLIII – XLIV – XLV – XLVI

[Separate-page view]

It never made sense to me how people could go through their whole lives without ever giving much thought to religious questions. For instance, this quotation from Steven Levitt (whose work I’m generally a fan of) seems to represent a pretty common attitude toward the subject:

I’m not religious. I don’t think much about God, except when I am in a pinch and need some special favors. I have no particular reason to think he’ll deliver, but I sometimes take a shot anyway. Other than that, I’m just not that interested in God.

Even among people who are religious, this relative lack of concern seems pretty normal; sure, they’ll say that they believe there’s “someone up there” if you ask them – but in truth, it’ll usually just be a casual kind of belief that they don’t really think about that much. Their attention will tend to be more focused on worldly concerns like their careers and hobbies and so on.

Like I said though, this mentality just never made any sense to me. In one sense, of course, I do understand where it’s coming from. There’s no way we can know for sure whether some higher power definitely exists or not, so what’s the point in spending too much time speculating? But just because we can’t know something for sure doesn’t mean that it’s a waste of time to even try to figure out anything about it. After all, a military commander might not know for sure whether an enemy force is planning to drop nuclear bombs on his country, but that doesn’t mean it’s not incumbent upon him to do absolutely everything he can to determine the likelihood of that outcome as best he can and respond accordingly. He may not be able to achieve absolute certainty, but the stakes are so high that the question demands his attention regardless. And the same is true of religious questions. If you think that there’s even a moderate level of uncertainty about whether a God exists or not, the stakes are just so astronomically high (even higher than the commander contemplating a nuclear attack) that the question demands your attention. You may not be able to know for sure whether a God really exists or not; but ultimately, that question is one with a definite yes or no answer. And regardless of what the answer is – whether there’s really a God or not – the implications of that answer are maximally consequential, perhaps more so than any other question.

I mean, imagine if there really were such a thing as God. Imagine if there really were such a thing as an eternal afterlife. If these things were actually real, then the significance of that fact would utterly dwarf everything in this world, everything we puny humans are currently doing with our lives, in the most profound way possible. Someone has just invented a new kind of phone? The stock market has just crashed? Okay, sure, those things are important – but meanwhile, looming over our planet is an all-powerful cosmic being capable of creating and destroying galaxies at whim, who may or may not intend to keep every living soul alive for the rest of eternity, and who may or may not have certain conditions that humans must follow within this arrangement in order to ensure that they spend this eternity in a state of infinite bliss rather than infinite torment. Doesn’t it seem like this might be a bit more important than the other stuff?

Similarly, let’s imagine the opposite scenario – if it turned out that there was actually no such thing as a God or an afterlife after all. For most people, this revelation would be equally earth-shattering. If, let’s say, you were a believer who fully expected to live forever in Heaven, only to find out that your belief was completely false, then wouldn’t that fact be just as much of a game-changer as learning that it was true? I mean, imagine what it would mean to realize for the first time that you weren’t going to live forever. Imagine some hypothetical character (like a wizard or a vampire or something) who was immortal, and who lived their life based on the belief that they were going to live forever – but then one day found out that no, in fact they only had about 30-50 more years before they utterly ceased to exist. That realization would surely feel like an absolute bombshell. It would be like one of us mere mortals thinking that we were going to live for another 30-50 years, but then finding out instead that in fact we were actually going to die within the next two hours. It would be a life-transforming, perspective-redefining shift. It would change everything.

So while it’s true that none of us can know for sure whether there really is some kind of higher power (at least not currently), the point here is just that the question of religion is an unbelievably important one – and the fact that billions of people hold such differing beliefs on the subject means that, no matter how you slice it, billions of people are wrong in some major way. This is a very big deal. After all, if religion were false, it would mean that the vast majority of humankind was living a massive lie – one that affected everything from their views on morality, to their stances on socio-political issues, to their attitudes toward death – and one that has led to countless fatalities over the centuries and could lead to countless more. If religion were false, it would be a bigger scandal than Watergate; it would be bigger than finding out that there were no WMDs in Iraq and that the entire war was based on false intelligence; hell, it would be bigger than finding out that the Holocaust and the Pearl Harbor attack had never happened and that the Axis Powers were the good guys acting in pure self-defense all along. If religion were false, then the sheer weight of that fact would dwarf every other fraud, scandal, conspiracy, and cover-up (real or imaginary) that has ever existed. And conversely, if religion were true – specifically, if a religion like Christianity were confirmed true – then it would be an even bigger deal, because it would mean that billions of our loved ones whom we had thought were dead were actually alive and worshiping joyously in Heaven – or agonizing in Hell – and that every single one of us would ultimately meet one of those two fates ourselves when we died, depending on certain very specific choices that we made (or didn’t make) during our short time on Earth. Not only that, it would mean that our entire earthly way of life would need to be massively overhauled. For instance, if Christianity were confirmed true, then the ideal system of government would certainly not be our current form of democracy; it would be a Christian theocracy that followed the teachings of the biblical law as closely as possible and existed for the sole purpose of serving Yahweh’s will. If Christianity were true, then the only rational use of your time would be to spend every waking moment learning as much about biblical teachings as you possibly could, following them as closely as possible, and trying to convince others to do the same. If Christianity were true, then the only thing that you would ever want occupying your thoughts would be God and his will; the only songs you would ever want to sing would be songs of worship; the only book you would ever want to read would be the Bible; and your most urgent moral obligation would be trying to rescue as many people as possible from the eternal torment that awaited them if you didn’t convert them. No other way of life would make sense.

To say that it matters whether such a religion actually is true, then, is a massive understatement. In fact, even if we ignored all the supernatural implications and were only concerned with how to make the best day-to-day moral decisions (both as individuals and as a society), the religious question would still be an absolutely fundamental one. As Mark Linsenmayer points out in a podcast conversation:

You can’t do the right thing unless you know what the right thing is, and you can’t know what the right this is until you have a conception of what “the right thing” means. You have to do metaethics before you can do ethics; and before you do that you have to know metaphysics […] so you have to know whether there’s a God or not who’s going to be telling you to do stuff – or if there is no God who’s not telling you to do stuff, then is there any sense in which you should do anything or not.

In this light, there’s a good case to be made that the truth of these metaphysical matters and their implications might in fact be the single most important issue in the world – because it’s from the answers to these questions that the answers to practically every other question we care about must emerge. Our ethics, our politics, our social structures – all of these things are downstream of whether we believe in God or not; and if our religious beliefs ever changed, then our attitudes toward all these things would significantly change as well. (I suspect, for instance, that a huge percentage – maybe even a majority – of current Republican voters originally joined the party not because of its economic policies or whatever, but because it better reflected their religious values on issues like abortion, popular culture, etc.; annd if Americans’ levels of religiosity suddenly became more like those of Europe, its political alignments – and therefore its economic and social policies – would start looking a lot more European as well in short order.) Religion is upstream of practically everything.

Having said all this, of course, I can’t help but come back to the conspicuous fact that most people – including even devout religious believers – don’t seem to take these matters nearly as seriously as all this. Aside from a small sliver of the population – the most obsessively fundamentalist monks, nuns, missionaries, and self-proclaimed holy warriors – most people still have lives of their own, outside of their religion, which occupy most of their time and energy. There are plenty of people who claim, for instance, that the Bible is the perfect and literal word of God; yet many of these same people have never actually read the book in its entirety (and likely never will), because they’re busy with other things.

How does that happen? Well, to me it would seem to suggest either that these people don’t actually believe in their religion as completely as they profess to, or that they haven’t fully internalized and thought through the implications of that belief (or both). After all, if you really believed that there was a book on your bookshelf right now that had literally been authored by the most intelligent being that had ever existed – the all-powerful creator and ruler of everything in existence – is there anything in the world that could possibly take priority over rushing to your bookshelf, seizing that book, and staying up all night and day reading it, poring over it, obsessing over it, and parsing every single miniscule detail to try and get as much from it as conceivably possible, then applying that to your life and executing its instructions as thoroughly as possible? I don’t think there could be – not if you really believed it.

At the risk of belaboring the point here, let me give one more analogy. Imagine this scenario: One day, you’re sitting in your living room idly watching reruns, when all of a sudden time freezes – your clocks stop, birds flying past your window are suspended in mid-flight – and a glowing portal opens up in front of you. Through it, you can see a group of alien beings watching everything that’s happening in the world on a giant computer screen – everything from your great-aunt brushing her teeth at home, to world leaders conducting top-secret meetings in undisclosed locations, to your own self staring dumbfounded at the portal – and from what you’re seeing, it’s clear that these alien beings are somehow monitoring and perhaps even controlling all the major events in the world. One of these beings turns toward you, says something in a strange language, and then hands you a thick sheaf of papers, before closing the portal and leaving you alone again in your living room. After a moment of shocked silence, you look down at the sheaf of papers and see some writing on them indicating that their contents explain not only who these alien beings are, but where they come from, what they are doing, what they want, and even the secrets of how they are able to see everything at will. How do you respond to this situation? Do you [A] realize that the significance of what you’ve just seen dwarfs everything you thought you knew about the world, and start obsessively reading through the alien papers and spending the next several hours (or days, or weeks, or months, or years) desperately trying to glean everything you possibly can from them? Or [B] stick the papers on a shelf somewhere and tell yourself you’ll maybe take a look inside them someday, before promptly forgetting about them and going back to your reruns?

I suspect any sane person would pick the former. And yet, the situation with the Bible is claimed by many to be much the same – so we have to ask, then, why aren’t they treating it with the kind of urgency it would seem to deserve? After all, if God actually came down from the sky right now and handed you a sheaf of papers that he had personally hand-written himself, and told you that it contained all the universe’s most important truths and all the instructions that humans needed to follow in order to live forever, would you really just stuff it on your shelf somewhere and forget to ever read it because you needed to mow the lawn or whatever? In other words, would you treat this hypothetical Word of God the same way you treat the actual non-hypothetical Bible in the real world? And if not, what does that say about what you truly believe? It seems like there could be a very serious disconnect there.

I’m not religious nowadays, but I used to be; and I took my faith very seriously – much more seriously than most of my fellow Christians did. I hadn’t quite internalized all of the above reasoning just yet, of course, so I never went so far as to join a religious order and devote every single waking second of my existence to religious pursuits, but at some level I did realize that if this stuff really was true – and I believed it was – then it was a big enough deal that it should be nothing less than the central focus of my life. Accordingly, I was one of those people whose entire identity was defined by their faith – the kind of person who, as Dan Barker puts it, “you would not want to sit next to on a bus.” I practically spent more time at the church than at home; I listened to Christian music almost exclusively; I performed in the church band every week; I daydreamed about going into the ministry constantly; I even wrote a short book of mini-sermons and went around sharing them with whoever would listen. And I wasn’t just doing these things out of some dry sense of duty or obligation, either – I felt the power and beauty of God’s grace in every fiber of my being; it was the force that gave me life and animated my every action. When I prayed, it was just as Evid3nc3 describes in his own testimony:

I [had] a relationship with Jesus, and I spoke to him in my mind; I would pray, and I would feel like I would hear answers from him. And sometimes it felt like it was a voice, sometimes it felt like Jesus was speaking to me through my relationships with other people, or through circumstances, like maybe something happened a certain way in my life and I felt like this was a message from God, from Jesus, speaking back to me, maybe answering my prayers.

Likewise, when I worshiped, it was just the kind of rapturous experience Barker recounts having experienced as a former Christian himself (I didn’t attend a church that did faith healings, but the overall emotional experience was largely the same):

When Kathryn Kuhlman started coming to Los Angeles for her regular faith-healing services at the Shrine Auditorium, our choir formed the initial nucleus of her stage choir. I was there for her first regular visit in the mid ’60s and for two years I hardly missed a meeting, remaining choir librarian as the group grew in size, eventually incorporating singers from dozens of charismatic churches in Southern California.

It was the sound of the organ, more than anything else, that established the mood of the place. With its dramatic sweeps and heady crescendos flooding the huge vaulted building, we felt engulfed by the presence of God’s Holy Spirit, breathing in, breathing out, laughing and crying for joy and worship. Here and there a woman was standing, arms reaching upward, eyes closed, praying in an unknown tongue. Wheelchairs and crutches littered the aisles. Hopeful candidates pressed to find a seat as close to the front as possible; the balconies were standing-room-only.

My responsibilities as librarian did not inhibit me from sensing the intense hopefulness of the occasion. Before Kathryn walked out on stage the building radiated that strange, eager beauty of an orchestra tuning up before a symphony. I would often watch her as she stood backstage, nervous yet determined, possessing a holy mixture of humility and pride, like a Roman or Greek goddess in her flowing gown. The audience was anxious. The Spirit was restless.

The organ crescendo reached a glorious peak as Kathryn regally walked out on stage. Those who could rose to their feet, praising God, weeping, praying. It was electrifying and intensely euphoric. I felt proud to be a witness to such a heavenly visitation.

Kathryn would often deny that she was conducting “healing meetings.” She stated that her only responsibility was obedience to God’s moving; it was His business to heal people, and it didn’t need to happen in every meeting. Of course, the people had come for miracles, and would not be disappointed. She often seemed uncertain how to start. She would pray, talk a little, preach somewhat freely, or just stand silently crying, waiting for God to move. He always moved, of course – but the audience couldn’t stand it, this delay of climax. (It was like the anticipation on Christmas mornings, waiting for Dad to finish reading the biblical nativity story before we could open the presents.)

In those early months, before local ministers began sitting on the stage in front of the choir, we singers were placed directly behind Kathryn in folding chairs. I always sat in the front row, right behind her, about six or eight feet from her center microphone, peering past her down into the sea of eager faces in the audience – the faces of people who had come to be blessed. The choir would often sing quietly behind the healings, “He touched me, yes, he touched me! And, oh, the joy that floods my soul! Something happened and now I know; he touched me and made me whole!” It was rapturous. Ecstatic.

After 20 or 30 preliminary minutes, which included a few choir numbers, the healings would begin. People would be ushered up to Kathryn, one at a time, some sitting in wheelchairs, to receive a “touch from God.” She would face the candidate, touching the forehead, and would either ask the problem or directly discern the need. Often the supplicants were “slain in the spirit,” meaning they fell backwards to the floor under God’s presence, often with arms raised in surrender. I sometimes had to pick up my feet when they fell in my direction. Kathryn had a “catcher,” a short, stocky, redheaded former police officer who would move behind the people and soften the fall. He was often quite busy. People would be dropping all over the stage, even choir members and ushers. He rushed back and forth like a character in a video game, never missing, though it was sometimes quite close.

It didn’t matter that the healings were visually unimpressive. We were in God’s presence and a miracle is a miracle. Sometimes an individual would discard crutches or push Kathryn around the stage in the unneeded wheelchair, things like that. But the healings were usually internal things: “Praise God! The cancer is completely gone!”

One very common cure was deafness. Kathryn would tell the person to cover the good ear (!) and ask if she could be heard. “Can you hear me now? Can you hear me now?” she would ask, speaking louder and louder until the person nodded. Then she would dramatically move away and speak softly to the person, who would jump and say, “I can hear you! I can hear you! Praise God!” The place would fall apart, people screaming and hopping. Miracles do that to people. It was an incredible feeling, an ecstasy beyond description. We felt embraced by the presence of a higher strength, participating in a group worship (hysteria), floating on the omnipresent surges of the organ music, joining in song with heavenly voices.

In one service Kathryn replied to the criticism that some of her healings were purely psychosomatic by saying, “But what if they are merely psychosomatic? Is that not also a miracle? Doctors will tell you that the hardest illnesses to cure are the psychosomatic ones.” God works in mysterious ways.

As I look back on it now, I can see that most of the “miracles” were pretty boring. The excitement was in our minds. I saw people walk up to the side of the stage in search of a healing, before being told by an usher to sit in a wheelchair to be rolled up to Kathryn. When Kathryn quietly told the person to “stand up and walk the rest of the way,” the crowd went wild, assuming that the person couldn’t walk in the first place. I never witnessed any organic healings, restored body parts or levitations. A few crutches and medicine bottles littered the aisles, but no prosthetic devices or glass eyes. The bulk of the “cures” were older women with cancer, arthritis, heart problems, diabetes, “unspoken problems,” etc. There was an occasional exorcism (mental illness?), too. We had come to be blessed and we were not to be cheated, taking the slightest cue to yell, sing and praise God. I think, in retrospect, the organist was the real star of the show, working with Kathryn to manipulate the moods. We were so malleable.

Experiences like that were tremendously affirming. When I was “seeing miracles,” it seemed so real, so powerful, that I wondered who in the world could be so blind to deny the reality of the presence of God. Nonbelievers must be stupid or crazy! Anyone who deliberately doubted such proof certainly deserved hell.

I used to pray and “sing in the spirit” all the time. Riding my bike around Anaheim, I would quietly speak in tongues, exulting in the emotions of talking with Christ and communing with the Holy Spirit. If you have never done it, it is hard to understand what is happening when people speak in tongues. I actually got goose bumps from the joy, my heart and mind transported to another realm. It’s a kind of natural high that I interpreted as a supernatural encounter. I’m certain there are chemicals released to the brain during the experience. (I know this is true of music and the cerebellum, but has anyone studied the brain during glossolalia?) While some of my friends may have been sneaking out behind the proverbial barn to experiment with this or that, I was having a love affair with Jesus. I didn’t think I was “crazy” – I was quite functional and could snap out of it at any moment, like taking off headphones – but I did feel that what I had was special, above the world.

Jesus said that “My kingdom is not of this world,” and I felt like my physical body was just a visitor to planet earth while my soul was getting messages “from home.” It gave me a sense of overwhelming peace and joy, of integration with God and the universe, of being wrapped in the loving arms of my creator. It caused everything to “make sense.” I’m not sure why, but it did. I simply knew from direct personal experience that God was real, and no one at the time would have been able to convince me that I was delusional. I would simply say, “You don’t know.” I had seen miracles. I had talked with God. I knew the truth and the world did not.

It was the same for me. When I was a Christian, the idea that my faith might somehow be false, or that there might be no such thing as God, seemed as absurd as the idea that, I don’t know, there was no such thing as the President of the United States or something (and that all the records and video footage of him had been faked somehow). It simply seemed ridiculous – so much so that it had never even occurred to me to seriously consider it as a possibility. That isn’t to say that my faith was “perfect,” of course – no one’s is. Obviously, if my faith had been completely impenetrable, then I wouldn’t have ultimately stopped believing. But as far as my core beliefs went, my belief in the existence of God was as rock-solid as any belief I’d ever held in my life.

When the first cracks in the armor finally did start to appear, then, they didn’t come in the form of big existential doubts. I knew my beliefs were right, so it wasn’t a matter of not believing strongly enough. Rather, they were more like what I guess you might call implementation issues. I sometimes felt like something wasn’t quite right with the way I was practicing my faith. Like for instance, whenever I was worshiping in a public setting (like at church), I couldn’t help but notice how I would sometimes catch myself making slightly more visible displays of emotion, or exaggerating my body language, when I knew other people were watching – as if I subconsciously imagined that if my fellow worshipers noticed me raising my arms and closing my eyes and singing even more passionately than normal, they’d be that much more impressed with how spiritual I was. Once I realized I was doing this, of course, it really bothered me; I didn’t want to feel like I was worshiping for an audience, but for God alone. But once I became conscious of it, it was hard for me to worship publicly without feeling self-conscious about how much of it was really authentic versus how much of it was “just for show.” Whenever I worshiped, it always felt like something I was having to do consciously. Try as I might to get completely swept away by the Holy Spirit, there was always some small part of my awareness, in the back of my mind, that felt like it was dispassionately monitoring the whole experience from afar and making conscious decisions about performance and execution, like a movie director directing a scene or something. To be sure, worship still felt like the most powerful and beautiful and real thing I had ever experienced – but at some level, it could also feel almost rehearsed at times. Even on those occasions when I did feel myself being swept up in the Spirit, there was always a small nagging sense in the back of my mind that maybe I was subconsciously “playing up” the experience so it would feel more dramatic, as if I were an actor trying to portray a more emotional experience than I was actually having.

This self-consciousness extended into other parts of my religious life too. For example, there were a few times when I attempted to read the Bible cover to cover – but I never managed to get very far; and the reason was because once again, I wasn’t entirely able to disentangle the way I knew I was supposed to feel from the way I actually felt. Deep down, the truth was I wasn’t actually that motivated to read the Bible for its own sake; I didn’t feel compelled to voraciously devour as much of it as possible due to a genuine desire to know what was written there, or an overwhelming conviction that this was the perfect word of God himself. Rather, I was more motivated to read it simply for the “street cred” that I would have gotten from doing so – i.e. for the moral status and the philosophical cachet of being someone who had really done their homework and knew their stuff. What I wanted wasn’t actually to read the Bible; what I wanted was to be a person who had read the Bible – and that was an important difference, even if it was one that was too subtle for me to even be explicitly aware of at the time.

But why was there this difficulty at all? Didn’t I believe that the Bible was, in fact, the perfect and literal word of God? Well, it wasn’t quite so simple. Certainly, I’d taken the Bible literally when I was younger; having grown up on Bible stories, I had always taken it for granted that Adam and Eve were real people, that Noah’s flood had really happened exactly as described, and so forth. But as I aged and became more aware of all the relevant scientific and historical facts that diverged from these stories, I came to recognize that a literal interpretation of the Bible simply wouldn’t be able to accommodate all the facts; so my way of thinking about these issues subtly shifted from an absolute hard-literalist line to a more abstract one. The more I grew and learned, the more I started to realize that, in fact, maybe what I really believed was not that these Old Testament stories were all literally true – maybe that was too simplistic an explanation for such a richly complex God anyway – but that they were metaphorically true, and that what really mattered was not the exact text itself, but the broader underlying message that permeated it. Sure, the universe may have actually been billions of years old and not the 6,000 years old that the Bible suggests – and sure, the creation of life may not have happened exactly as the Book of Genesis describes – but to take these stories literally was to miss the point; a more sophisticated interpretation would recognize that the six biblical “days” of creation were actually metaphors for eons, that Adam and Eve were actually metaphors for humanity in general, etc. At any rate, I still believed that the Bible was divinely inspired, and I still revered it as a holy source of wisdom. But in truth, I think I regarded it as sort of secondary, in a sense. The real focus of my faith was God himself, not the words written about him. My faith wasn’t so much built around the Bible, but around my own personal experiences of God’s love and majesty, and the impact he had on my own life.

Of course, maybe you are one of those believers who takes the Bible literally and considers it to be 100% inerrant. In that case, let me just take a few sections here to explain why I could never quite fully commit to that interpretation myself. A lot of the reasons I’ll be giving here, of course, are things that I wasn’t actually cognizant of while I was still religious, except in a sort of distant, peripheral way; for instance, I didn’t know all the different ways that the Bible contradicted science until after I’d already been a nonbeliever for a while. When I was a Christian, I just had a kind of vague, low-level awareness that there were in fact some discrepancies there (though they didn’t feel important enough to detract from Christianity’s core message). I simply didn’t think enough of them at the time to pay them much mind. But needless to say, those seemingly small details had a way of adding up and, in the end, making a big difference – so hopefully, by detailing some of these issues explicitly here, I’ll be able to give some insight into where the seeds of my eventual deconversion ultimately came from.

I should probably give a disclaimer right up front – if you’re religious, a lot of the things I’m going to be saying here will strongly conflict with some of your most cherished beliefs. I’m going to try not to be needlessly inflammatory, but in some cases it’ll probably just be unavoidable that some of the things I say will really rub you the wrong way. In particular, some of the quotations and video clips I’ll be referencing – and there are a lot of them – go pretty heavy on the anti-religious snark. But for better or worse, the points they make are part of what convinced me to change my beliefs, so I feel like it would be an incomplete account if I didn’t include them. Just know that my goal here isn’t to upset or offend; in fact, I’m not even necessarily trying to deconvert you (at least, that’s not the main purpose of this post). My main goal here is just to explain where I’m coming from – what I believe now, and how I got there – in as clear a manner as I can; and hopefully, that might prove useful to any believer who struggles to understand how anyone in their right mind could lack a belief in God, and who genuinely wants to understand what possible reasoning there even could be for such a stance. I talked in my last post about how I think discussions like this are better served by trying to build bridges of understanding than by trying to score debate points and beat the other side – and in the case of religion specifically, I feel like both sides tend to get a lot more out of trying to understand where their views differ (and why) than they get out of straw-manning each other’s positions and trying to destroy each other (e.g. nonbelievers accusing believers of being empty-headed sheep who believe whatever they’re told, believers accusing nonbelievers of knowing deep down that God is actually real but choosing to reject him anyway out of a selfish desire to live sinfully, etc.). Still though, even if you disagree with me on this approach and are a true diehard – even if your only goal in life is to convert every nonbeliever to Christianity – I daresay you can’t expect to have a solid enough theoretical footing to successfully dissect and refute opposing arguments unless you actually understand those arguments on their own terms – so if nothing else, hopefully this post will at least be able to serve as a partial collection of what the arguments actually are, and what the reasoning behind them is, that you can use as a handy reference.

So all right then – with all the disclaimers out of the way, let’s get down to it.

The first reason why I don’t think the Bible can be considered infallible is because, to put it bluntly, it’s hard to see how such a thing even could be possible, just in basic functional terms. The Bible contains so many contradictions that to say that all of its assertions must be true just seems logically incoherent, like saying that a triangle can have four corners or something. I mean, if you were to read a biography of George Washington that claimed in the first chapter that he was born in in 1732 to parents named Mary and Augustine, but then said in the second chapter that he was born in 1736 to parents named Abigail and William, you might not necessarily know which of these accounts (if either) was the correct one – but what you would know is that the biography itself must be flawed, because it wouldn’t be possible for both accounts to be true at once. And the biography’s imperfection would become even more glaring if it kept making hundreds more such contradictory statements throughout its pages.

Unfortunately for biblical literalists, though, this is exactly what you see with the Bible. It’s chock-full of these kinds of contradictions – and although it’s possible in some cases to squint your eyes and stretch the limits of your credulity to imagine ways that these contradictions might be resolved, in many cases they’re just irreconcilable.

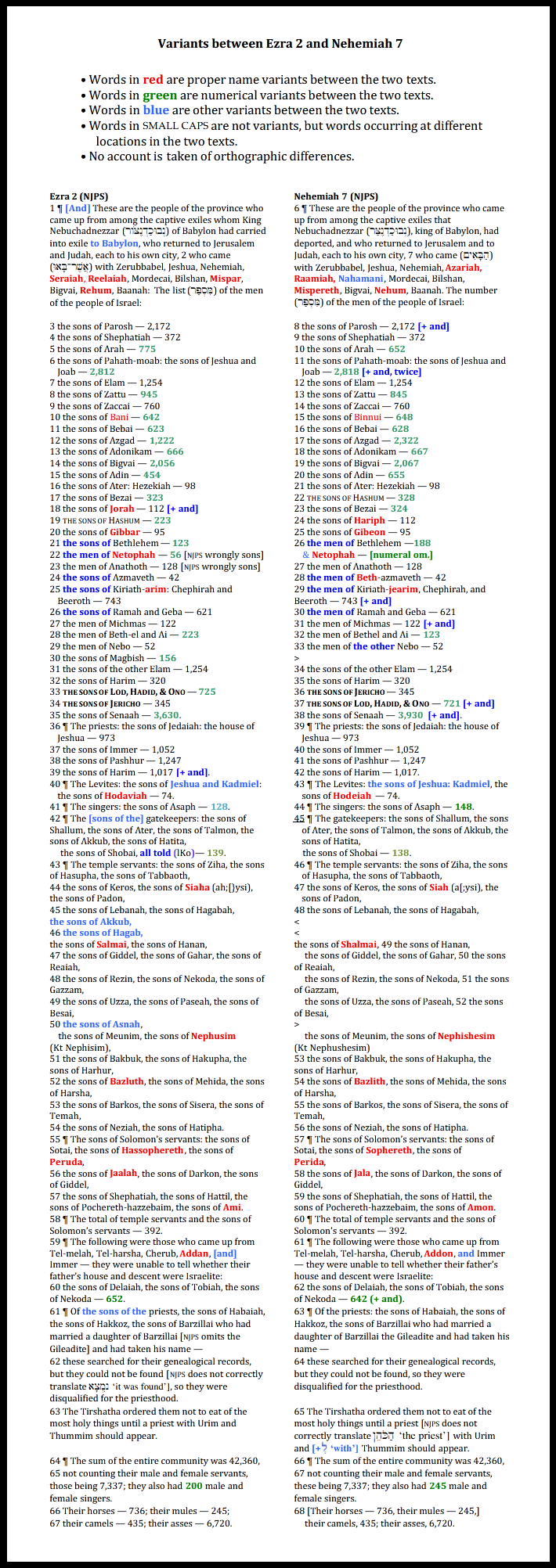

Some of the contradictions, of course, are fairly mundane details that might be easy to miss at first. How old was King Jehoiachin when he began his reign? (According to 2 Chronicles 36:9, he was eight; but according to 2 Kings 24:8, he was eighteen.) Who was Samuel’s firstborn son? (According to 1 Samuel 8:1-2, it was Joel; but according to 1 Chronicles 6:28, it was Vashni.) Where did Josiah die? (According to 2 Kings 23:29-30, he died at Megiddo; but according to 2 Chronicles 35:23-24, he died in Jerusalem.) Was Isaac Abraham’s only son when he was nearly sacrificed? (According to Genesis 22:2 and Hebrews 11:17, he was; but according to Genesis 16:15-16 and Galatians 4:22, Abraham already had another son.) How many members of each Jewish family returned to Judah from their captivity in Babylon? (Ezra 2 and Nehemiah 7 each give detailed lists of how many people there were from each family, but the two accounts contradict each other in over a dozen places.)

Like I said, pretty mundane. But there are other contradictions that are harder to overlook. The creation story, for instance, is the most prominent event in all of Christianity – but the Book of Genesis gives two contradictory descriptions of how it supposedly happened. In Chapter 1, it describes God creating both Adam and Eve at the same time, on the sixth day of creation, after creating all the other animals. In Chapter 2, though, God creates Adam first, then creates the animals so that Adam won’t be alone, then gives Adam the task of going through the entire animal kingdom and naming each creature individually (which realistically would have taken months or years); and it’s only after Adam has completed this project and failed to find a suitable companion that God finally decides to put him to sleep and create Eve out of his rib. These aren’t two complementary accounts of the same sequence of events; they’re two different stories.

Or take the story of Noah’s ark. We all know the classic image of Noah leading all the different species of animals onto his boat, two by two; and sure enough, that’s how events are described in Genesis 6:19, 7:8-9, and 7:14-15 – every species boards the ark in twos (one male and one female). But according to Genesis 7:2-3, there are actually seven of each animal – or fourteen, depending on your translation – loaded onto the ark (except for the unclean ones like pigs and dogs, which are only loaded in twos). This one really threw me for a loop when I first learned of it – who had ever heard of Noah bringing animals onto the ark in sevens? But sure enough, it’s right there in the book; I’d just somehow managed to never see it.

I could keep going here; these kinds of contradictions come up again and again – not just here and there, but hundreds of times – throughout the Bible. I’m only giving a few Old Testament examples right now to demonstrate the general point, but they become even more egregious once you get to the New Testament (as we’ll get into later). The tongue-in-cheek clip below from NonStampCollector does a good job of putting into perspective just how extreme the problem is:

Again, it’s true that some of these contradictions only concern relatively minor details and probably don’t have much bearing on the big-picture questions of existence. (Who really cares how old Jehoiachin was when he became king?) But regardless of how minor these points may be for the broader overarching message of Christianity, they are most definitely not minor for the specific claim that the Bible is inerrant – because if you really want to make that claim, then even a single tiny fault is enough to disconfirm it. If a book contains flaws, then by definition, it’s imperfect.

There are ways of trying to rationalize the contradictions away, of course – and if you think your religion requires you to believe that the Bible is perfect, then it’s only natural that you’ll want to try – but the mental gymnastics you have to put yourself through to come up with some convoluted explanation for every single disparity you encounter (as I tried to do myself for years) just start to feel forced and ridiculous after a while. Bart Ehrman recounts his own experience with this kind of cognitive dissonance during his time in seminary:

A turning point came in my second semester, in a course I was taking with a much revered and pious professor named Cullen Story. The course was on the exegesis of the Gospel of Mark, at the time (and still) my favorite Gospel. For this course we needed to be able to read the Gospel of Mark completely in Greek (I memorized the entire Greek vocabulary of the Gospel the week before the semester began); we were to keep an exegetical notebook on our reflections on the interpretation of key passages; we discussed problems in the interpretation of the text; and we had to write a final term paper on an interpretive crux of our own choosing. I chose a passage in Mark 2, where Jesus is confronted by the Pharisees because his disciples had been walking through a grain field, eating the grain on the Sabbath. Jesus wants to show the Pharisees that “Sabbath was made for humans, not humans for the Sabbath” and so reminds them of what the great King David had done when he and his men were hungry, how they went into the Temple “when Abiathar was the high priest” and ate the show bread, which was only for the priests to eat. One of the well-known problems of the passage is that when one looks at the Old Testament passage that Jesus is citing (1 Sam. 21:1-6), it turns out that David did this not when Abiathar was the high priest, but, in fact, when Abiathar’s father Ahimelech was. In other words, this is one of those passages that have been pointed to in order to show that the Bible is not inerrant at all but contains mistakes.

In my paper for Professor Story, I developed a long and complicated argument to the effect that even though Mark indicates this happened “when Abiathar was the high priest,” it doesn’t really mean that Abiathar was the high priest, but that the event took place in the part of the scriptural text that has Abiathar as one of the main characters. My argument was based on the meaning of the Greek words involved and was a bit convoluted. I was pretty sure Professor Story would appreciate the argument, since I knew him as a good Christian scholar who obviously (like me) would never think there could be anything like a genuine error in the Bible. But at the end of my paper he made a simple one-line comment that for some reason went straight through me. He wrote: “Maybe Mark just made a mistake.” I started thinking about it, considering all the work I had put into the paper, realizing that I had had to do some pretty fancy exegetical footwork to get around the problem, and that my solution was in fact a bit of a stretch. I finally concluded, “Hmm… maybe Mark did make a mistake.”

Once I made that admission, the floodgates opened. For if there could be one little, picayune mistake in Mark 2, maybe there could be mistakes in other places as well. Maybe, when Jesus says later in Mark 4 that the mustard seed is “the smallest of all seeds on the earth,” maybe I don’t need to come up with a fancy explanation for how the mustard seed is the smallest of all seeds when I know full well it isn’t. And maybe these “mistakes” apply to bigger issues. Maybe when Mark says that Jesus was crucified the day after the Passover meal was eaten (Mark 14:12; 15:25) and John says he died the day before it was eaten (John 19:14) – maybe that is a genuine difference. Or when Luke indicates in his account of Jesus’s birth that Joseph and Mary returned to Nazareth just over a month after they had come to Bethlehem (and performed the rites of purification; Luke 2:39), whereas Matthew indicates they instead fled to Egypt (Matt. 2:19-22) – maybe that is a difference. Or when Paul says that after he converted on the way to Damascus he did not go to Jerusalem to see those who were apostles before him (Gal. 1:16-17), whereas the book of Acts says that that was the first thing he did after leaving Damascus (Acts 9:26) – maybe that is a difference.

Nate Gabriel recalls having a similar experience himself:

I used to be a fundamentalist, and it was [Jonah’s] fish that first convinced me there could be mistakes in the Bible. Not because the whale isn’t really a fish, but because the Bible, going back to the earliest documents we have, is inconsistent about its gender. It uses the word three times: The fish (“dag,” masculine) swallowed Jonah, Jonah was inside the fish (“dag’ah,” feminine), and then Jonah was vomited up by the fish (masculine again).

Wikipedia told me that the Orthodox Jewish explanation is that there were multiple fish and Jonah got transferred into a larger and more comfortable one when he gained more faith. I concluded that hey, there can be typos in the Bible after all.

And if you’re really looking for typos, probably the best place in the Bible to find them is the Book of Revelation, which in its original Greek text is so full of basic grammatical errors that it prompted Friedrich Nietzsche to comment, “It is a curious thing that God learned Greek when he wished to turn author – and that he did not learn it better.”

At the end of the day, it seems like the best way to resolve the issue of biblical contradictions is simply to acknowledge the possibility that its authors may in fact have made a few mistakes at various points. That doesn’t necessarily mean that they weren’t divinely inspired – even an imperfect book might have been inspired by God – all it means is that the text of the Bible was transcribed by fallible humans, not directly written firsthand by God himself. And even the Bible itself will openly concede that much; aside from the Ten Commandments, which supposedly were chiseled directly into the stone tablets by the hand of God himself (Exodus 31:18, 32:16; Deuteronomy 9:10), the Bible is quite clear that, for instance, the Pauline epistles (Galatians, Romans, Ephesians, etc.) were written by Paul, the books of Jeremiah and Ezekiel were written by Jeremiah and Ezekiel, and so forth. It wasn’t God who wrote the Bible – it was men. And as verses like Ecclesiastes 7:20 and Romans 3:10 teach, no man is perfect (although, awkwardly enough, the Bible even manages to contradict itself on that particular point – as in verses like Genesis 6:9 and Job 1:1, 1:8, and 2:3, which describe men like Noah and Job (among others) as perfect and blameless).

The fact is, the text that we know today as the Bible wasn’t just handed down from the heavens, in its current form, fully complete. It emerged as the result of a very long and messy process that spanned centuries and involved thousands of people – with lots of edits, revisions, additions, subtractions, translations, and mistranslations along the way.

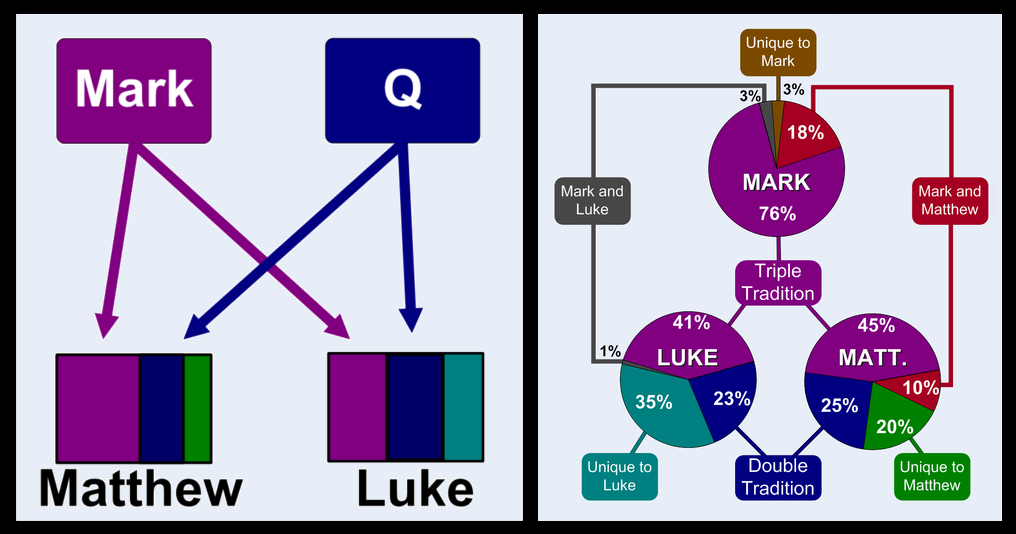

This whole process is actually pretty fascinating when you get into the historical details. Traditionally, Christianity teaches that the first few books of the Bible – Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy – were written by a single author, namely Moses. But the historical and textual record shows that these books weren’t actually written by a single author at all, but were combined from multiple sources over the years. Biblical scholars (a sizable portion of whom are Christians themselves) have a couple different models for breaking down the exact composition – one of which, the Documentary Hypothesis, is illustrated in simplified form by Evid3nc3 below (excerpting from his video here); what they all universally affirm is that the single-author model is untenable.

This would make sense, of course, considering that Deuteronomy describes Moses’s death and burial, along with other events that happened afterward; so clearly (for this and other reasons) Moses couldn’t have written the whole thing himself. (Although if he did, it would add a pretty amusing dimension to verses like Numbers 12:3: “Now Moses was a very humble man, more humble than anyone else on the face of the earth.”)

But the existence of multiple authors also makes sense of a lot of other things, including all those contradictions. It explains, for instance, why the creation story takes the odd form that it does, with two contradictory descriptions of what happened – because it actually was originally two different accounts, and it was only later that they were (somewhat clumsily) combined into the same narrative. As mentioned in the clip above, scholars were able to disentangle these two accounts by noticing certain telltale signs in the text, like the fact that one account always refers to God as “Yahweh” and uses one particular writing style, while the other always refers to God as “Elohim” and uses a noticeably different style. And by tracing these regularities throughout the other books of the Old Testament, these scholars were able to uncover explanations for the other contradictions as well – like the “twos” versus “sevens” contradiction in the Noah story, or the fact that Genesis 6-7 describes Noah assembling the animals and boarding the ark with his family a good three or four times, one right after another, in a manner that would otherwise just seem weirdly redundant.

It’s the same story with all those other incongruities throughout the Old Testament; the reason why so many different parts of the Bible disagree on so many details is because originally, they weren’t part of the same volume at all, so the issue of mutual consistency didn’t really come into play as much. Different sections of what would eventually become the Jewish Torah (AKA the Old Testament) started off as their own independent works, existing separately from one another and floating around the Middle East along with countless other books of supposedly divine scripture. It took centuries of mixing and matching before the Torah started to take shape in its modern form; and even once it did, human editors continued to alter it – adding new passages, removing others, and making various changes as they saw fit.

As for the New Testament books, obviously they were added to the canon much later – but again, they weren’t just handed down from the heavens one day in a single tidy volume. Like the Old Testament, the New Testament was assembled from multiple different sources and extensively revised over the course of several centuries. When the Christian religion first started out, the different churches scattered across the Middle East all had different books of scripture that they considered sacred – some of which were shared by other churches, others of which weren’t. There wasn’t an official biblical canon; every church just used whichever writings about Jesus they liked best at the time. Needless to say, having such a hodgepodge of competing texts tended to muddle things up quite a bit in terms of Christian doctrine – and at times these differences were so pronounced that they caused real tensions to flare up between the various Christian factions. There were sects like the Ebionites and the Adoptionists, for instance, who believed that Jesus was 100% human and only became the Messiah after God adopted him into that role (i.e. he was not equal to God, but was simply God’s instrument) – while other sects, like the Docetics and the Basilideans, believed that Jesus was 100% divine all along and that his physical body was only an illusion (so he was never really crucified, but only appeared to be). There was a sect called Marcionism that rejected the Old Testament scriptures altogether and insisted that Jesus’s mission was to overthrow the angry and vindictive Old Testament God (who was actually a lesser demigod) and reveal the higher God of love and forgiveness instead – the true God. (In fact, Marcion himself was the first person ever to compile a canon of Christian scriptures – a “New Testament” that was separate from the “Old Testament” – for precisely this reason.) There was even a sect called the Carpocratians who (allegedly) believed in reincarnation and taught that in order to finish one’s cycle of reincarnation and ascend to Heaven, one first had to experience everything in life – including committing every possible sin. (You can imagine the kind of debauchery that this would have led to.)

Suffice it to say, for the first few centuries of Christianity’s history, the actual doctrine of the religion was something of a free-for-all. It was only when things finally reached a boiling point in AD 325 that a bunch of the religion’s most prominent leaders decided to convene at Nicaea and hold a series of votes to decide on what the answers to the key theological questions of Christianity (like whether Jesus was human or divine) should actually be. To believers today, of course, it might seem galling to even imagine that the most holy and sacred of truths might be decided by something as prosaic as a show of hands by some random committee hundreds of years after Jesus’s death – but it was only after this meeting (along with a series of other such meetings spanning the next few centuries) that something resembling a sort of official Christian consensus began to emerge. And it was also during this period that the leading figures within the Church finally came to something of a consensus regarding which specific combination of books should serve as the official sacred canon – i.e. the Bible.

This was not a straightforward process, to say the least; there was a lot of politics involved, and there was never really a point where the matter was settled in anywhere near as definitive a manner as you might imagine. Several of the books that we see in our Bibles today, for instance – Titus, 1 and 2 Timothy, etc. – are completely absent from the earliest copies of the Bible. Books like Hebrews, James, 2 and 3 John, 2 Peter, Jude and (especially) Revelation were considered particularly controversial additions that took centuries to finally gain mainstream acceptance into the canon. Some of the most important passages in the Bible – like the story in John 8 where Jesus spares the adulteress with the admonition “Let he who is without sin cast the first stone,” or the line in Luke 23 where he’s dying on the cross and says “Father, forgive them, for they do not know what they are doing,” or even the crucial section at the end of Mark where the resurrected Jesus appears to his followers and then ascends into Heaven – weren’t part of the original text of those books at all, and were only added in by Christians centuries later. Other passages were altered or added to try and cover up obvious contradictions and mistakes (like 2 Samuel 21:19, which says that it was Elhanan, not David, who killed Goliath – and which KJV translators later altered to say that Elhanan killed “the brother of Goliath,” not Goliath himself). And not only that, but there were still other books that originally were included in the earliest versions of the Bible but were later removed – such as the Epistle of Barnabas, 1 and 2 Clement, and The Shepherd of Hermas. As Sam Harris notes, “For centuries [these books were] considered part of the canon, and then [were] later jettisoned as false gospel. Generations of Christians lived and died being guided by gospel that is now deemed both incomplete and mistaken.” The Bible that we know today actually still includes references to a number of these books throughout its pages, often citing them as sacred sources of prophecy and miracle accounts. Needless to say, though, this raises some serious problems for the idea that the modern Bible is God’s perfect word; why would a truly holy book cite a bunch of other books as containing holy knowledge if they were actually false gospel?

But that’s the thing – there are so many inconsistencies in the Bible, and so many thousands of discrepancies between all the different versions of the Bible that have existed throughout history, that even just asking whether the Bible is infallible is a premise that refutes itself. As Ehrman puts it: “When people ask me if the Bible is the word of God, I answer ‘which Bible?’”

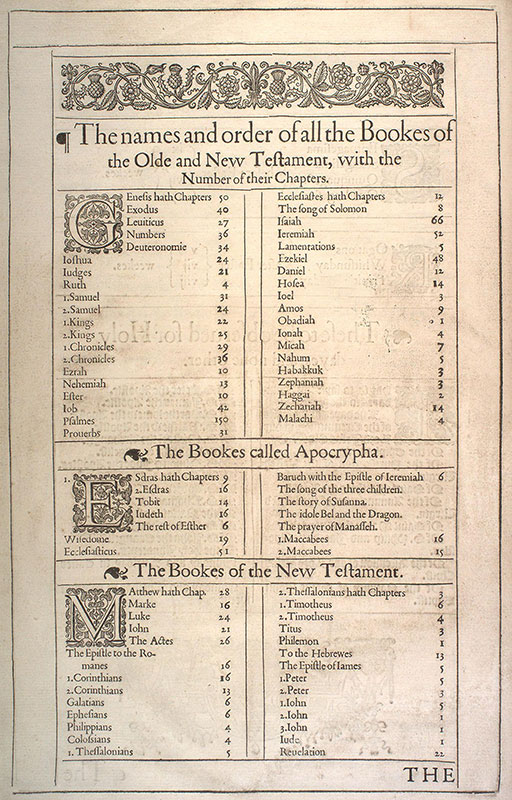

To this day, there are multiple competing versions of the Bible, and each has its own different combination of books that it considers canonical. (This is another one of those facts that I somehow managed to go my entire life as a Christian without knowing, but which totally blew my mind when I found out about it years later.) The Catholic Bible, for instance, includes all the books featured in the Protestant Bible, plus several additional ones: 1st and 2nd Maccabees, Baruch, Tobit, Judith, The Wisdom of Solomon, Sirach (AKA Ecclesiasticus), some additional passages in Esther, and some additional passages in Daniel (namely Susanna, the Prayer of Azariah and the Song of the Three Holy Children, and Bel and the Dragon (a story in which, yes, Daniel slays a real-life dragon)). Bibles used by the Orthodox Church – the second-largest Christian denomination after Catholicism – also include all these books (known collectively as the Apocrypha), plus 1st and 2nd Esdras, The Prayer of Manasseh, 3rd Maccabees, and Psalm 151. And in fact, even the original King James Version of the Bible, which most Protestants regard as the definitive version of God’s word, includes these books; it was only around the mid-1800s that Bible publishers quietly started dropping them from most Protestant editions.

(You might also notice individual verses like John 5:4, Acts 8:37, and 1 John 5:7 missing from your Bible depending on which translation you’re using; that’s because those verses were later interpolations, not part of the original text, so some biblical editors opted to remove them while others left them in.)

So to sum up, then, although it surely would have made things much easier for everyone if God had simply dropped the Bible from the sky in a perfectly finished, self-contained form (as he supposedly did with the Ten Commandments), this isn’t even close to what actually happened. There was never a single volume that we could point to and say, “There, that’s the original Bible.” What actually existed were a bunch of manuscripts, written by a wide range of different authors, that sometimes contradicted each other and sometimes made mistakes. None of those original manuscripts survived to the present day, so we don’t have them on hand to use as a reference. All we have are copies of copies of translations of copies of translations of copies, that were passed along from person to person over the course of centuries – accumulating mistranslations, editorial additions, redactions, and other alterations and mistakes along the way, like a game of telephone.

Even professional Christian apologists, if backed into a corner, will acknowledge that all this human error is to blame for many of the Bible’s faults. When faced with the “how old was Jehoiachin when he became king” contradiction, for instance, the prominent apologist Matt Slick concedes, “The discrepancy in ages is probably due to a copyist error.” He quickly follows it up, of course, with “Does this mean the Bible is not trustworthy? Not at all. Inspiration is ascribed to the original writings and not to the copies.” But the problem, like I said, is that we don’t have any of the original writings. So even if you assert that those lost scriptures – the original ones – were inerrant, that doesn’t do you much good if you also want to claim that the Bible today should be followed because it’s inerrant – because the only Bibles people are following today, i.e. the only Bibles that still exist, are the faulty copies. Ehrman asks the crucial question: “If God inspired the Bible without error, why hadn’t he preserved the Bible without error? I couldn’t think of a good answer then, and I still can’t think of a good answer now.”

No matter how you slice it, there’s just no way around the fact that the book we know today as the Bible is an imperfect one. The humans who wrote, compiled, and edited it may have been doing the best they could with the information they had at the time – or they may have been hopelessly biased – but either way, at the end of the day, they were only human. They still made mistakes; they still made faulty assumptions; and they still leapt to false conclusions at times. This is why the Bible contains the contradictions that it does – and it’s also why it contains so many other mistakes as well.

After all, the Bible doesn’t just contain internal inconsistencies, in which it disagrees with itself; it also contains external inconsistencies, in which it disagrees with realities of the outside world. Some of these errors are pretty minor (albeit still problematic for the claim that the Bible is perfectly inerrant); for instance, Leviticus 11 says that hares “chew the cud,” and that bats are a type of bird, and that beetles and grasshoppers only have four legs (none of which is true, obviously). But a lot of the scientific and historical mistakes are much more significant.

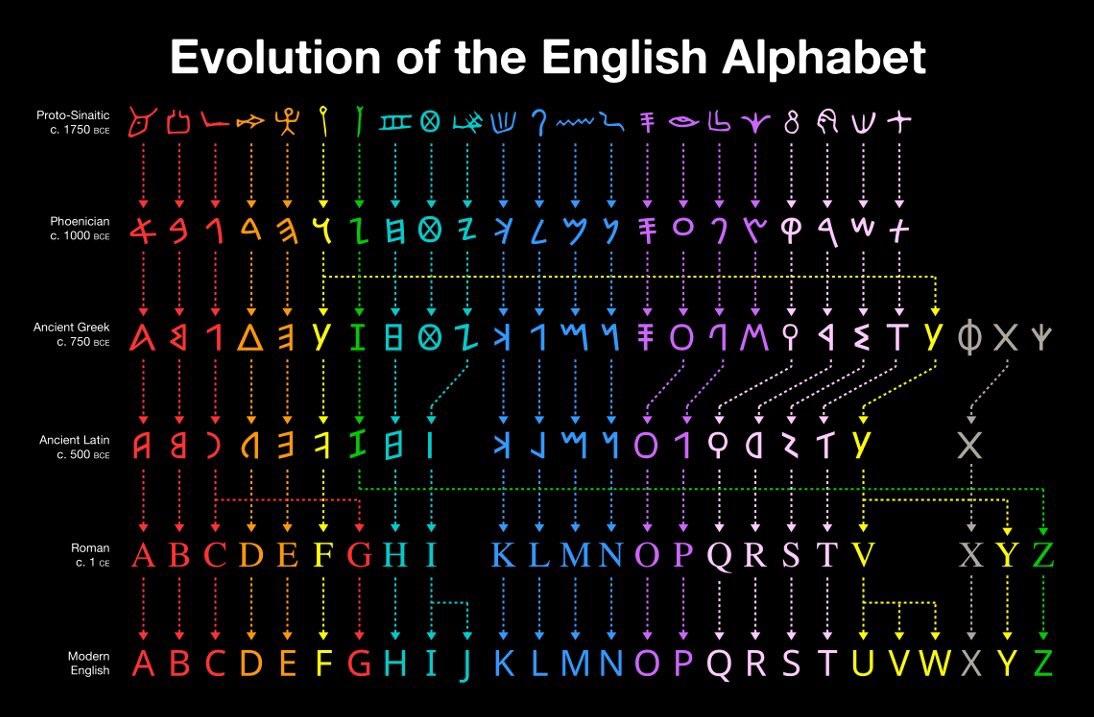

Just to take one example, consider the Tower of Babel story in Genesis 11. According to the story, all the humans on Earth originally shared a single common language – but one day, about 4,000 years ago, they decided to build a tower tall enough to reach Heaven itself, and God responded by cursing them so that they would all start speaking different languages and would therefore be unable to finish their task; and that’s why we have all the different languages around the world that we have today. But leaving aside some of the obvious questions here, like why this story considers Heaven to be a literal physical location in the sky, or why God would feel threatened by a species that was able to coordinate well enough to build such a tall tower, the central flaw of this story is the fact that it simply isn’t how all the world’s different languages came to exist. The story is just factually false. Different languages didn’t abruptly appear one day out of nowhere; they evolved and branched into different variations over the course of thousands of years. Everything that has ever been written reflects this – if you look at something written by Shakespeare, for instance, the English he uses is noticeably different from the English we use today; if you go back even further and look at something written by Chaucer, the language becomes even less recognizable as English; and if you go back further still and read Beowulf, you can’t even tell that it’s English at all. You can even trace linguistic evolution in this way using old translations of the Bible; the Middle English used in Wycliffe’s Bible is starkly different from the English used in modern translations. And you can do this for every other language too, not just English – you can trace their evolution through literary works, backtrack etymology, compare their grammar and syntax with those of other languages, and so on. The entire field of historical linguistics consists of cataloguing where these languages came from and how they evolved; and the verdict is conclusive – languages didn’t just appear all at once some 4,000 years ago. The Tower of Babel story isn’t a historical one. At best, it’s a convoluted metaphor. More realistically, it’s just a legend, handed down from a time when such legends were ubiquitous. Maybe it was loosely based on some real event, like the construction of the 300-foot Etemenanki ziggurat in Babylon, which was interrupted at around the same time as a general decline in literacy in the region due to Babylon’s fall. But if that’s the case, then the Tower of Babel story can only be called “true” in the same sense that Game of Thrones (which is loosely based on the historical Wars of the Roses) can be called “true.” There was no divine intervention there; it was just a normal historical event that happened in the same way that historical events normally happen.

And the same applies to nearly all of the Bible’s other key stories; whatever their value as allegory might be, a literal reading of them just isn’t tenable. Let’s take a few minutes to look at the story of Noah’s flood, for instance – which supposedly happened about a hundred years before the Tower of Babel. Already, this chronology should be raising some red flags; are we to believe that the mere three fertile couples who survived the flood (Noah’s sons and their wives) were able to repopulate the entire earth in only a hundred years? According to Genesis 10, there were apparently enough people just three generations after the flood not only to build a tower to Heaven, but to populate the cities of Erech, Accad, Calneh, Ninevah, Rehoboth, Calah, Resen, Sidon, Gerar, Sodom, Gomorrah, Admah, Zeboim, Lasha, Mesha, and Sephar – despite the fact that Noah’s family tree of descendants only consisted of a few dozen people.

Leaving aside that particular plot hole, though, the other problems with the flood story are so numerous that it’s hard to even know where to begin. For starters, there are just all the logistical impossibilities. A wooden ship the size of Noah’s ark (450 feet) would have been unable to remain afloat, because the flexural strength of wood just isn’t sufficient to prevent separation between the seams at that scale. Various attempts have been made to build seaworthy recreations of Noah’s ark using only the materials mentioned in the story, but all have failed; the only wooden ships in history that have even come close to 450 feet have required metal reinforcement and constant use of mechanical pumps to keep their hulls from flooding.

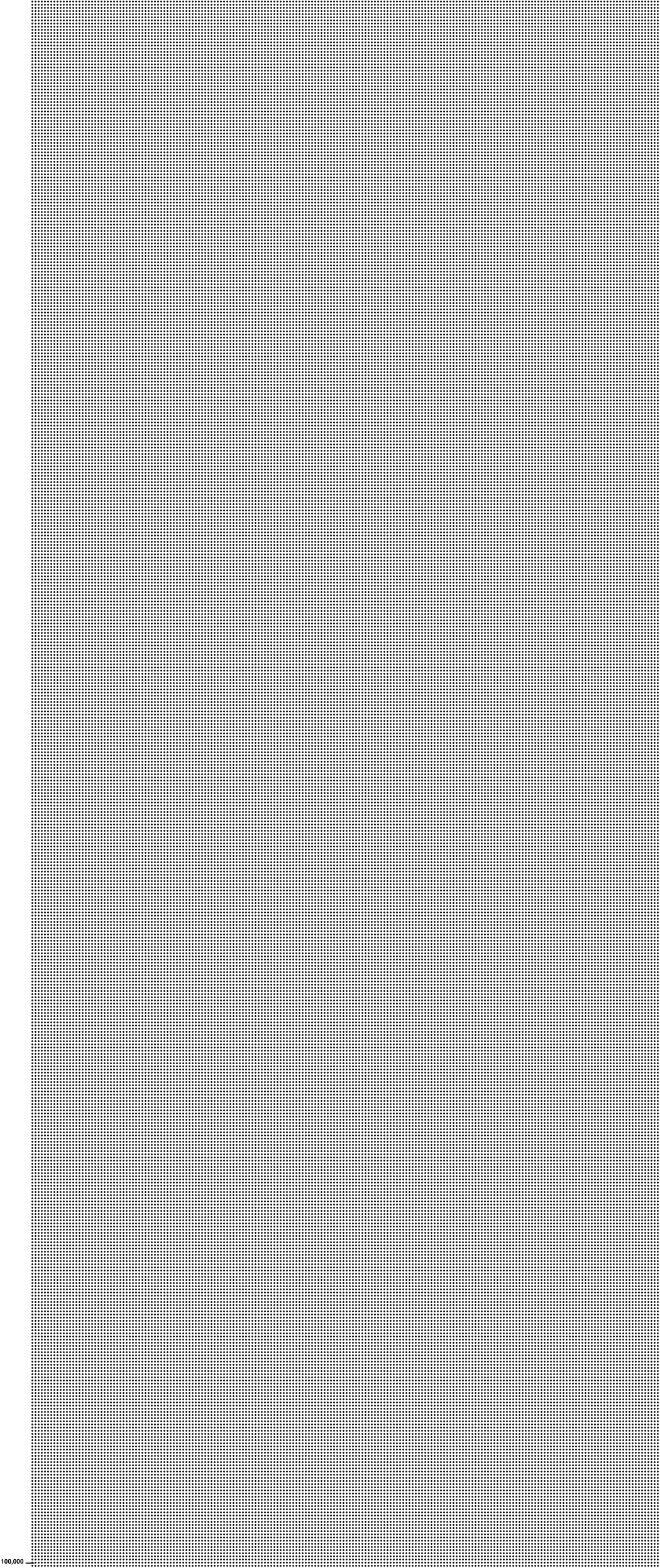

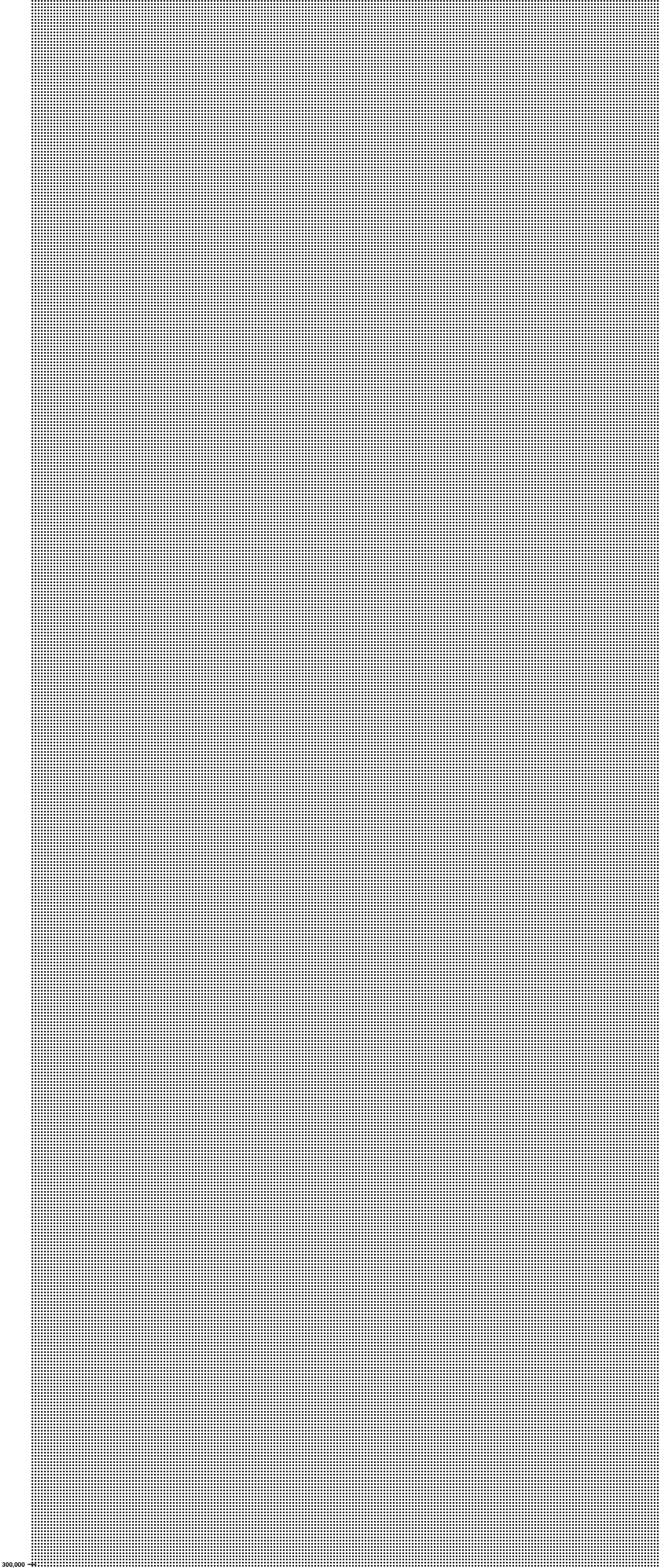

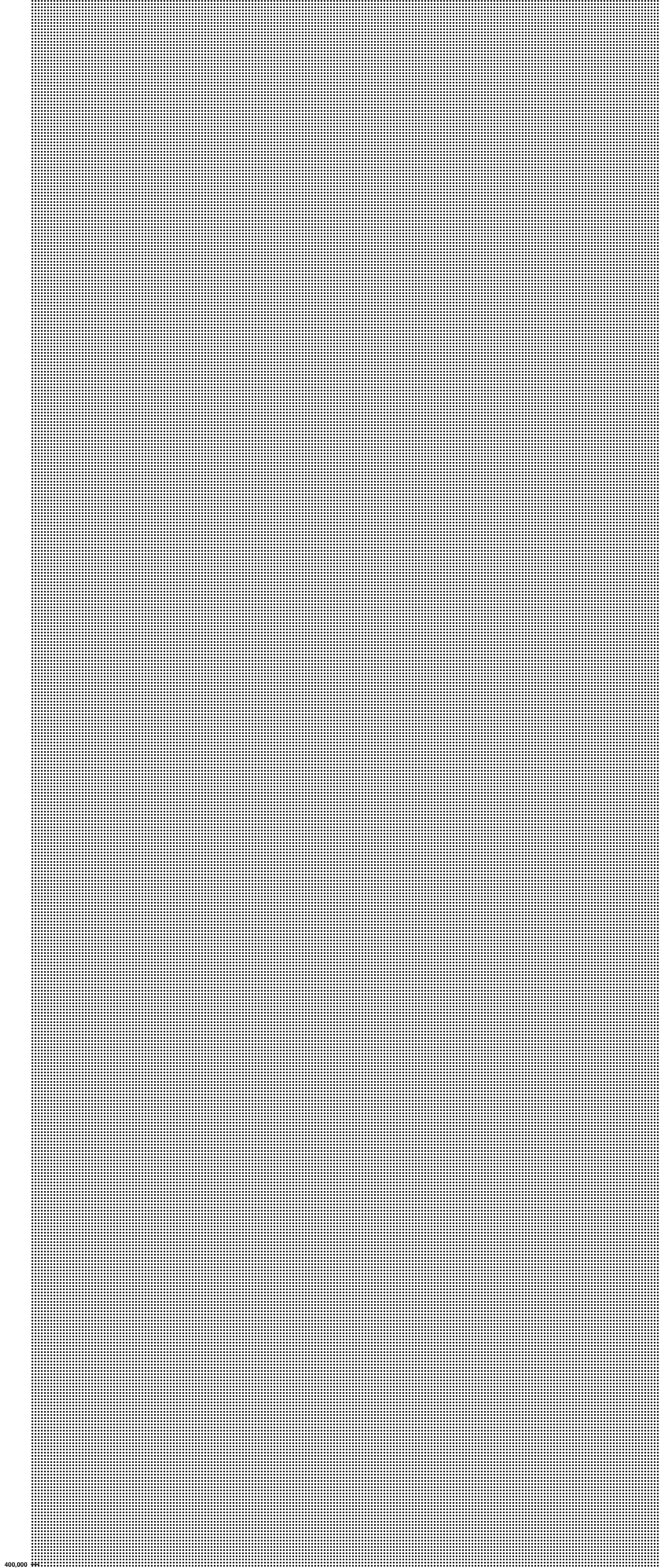

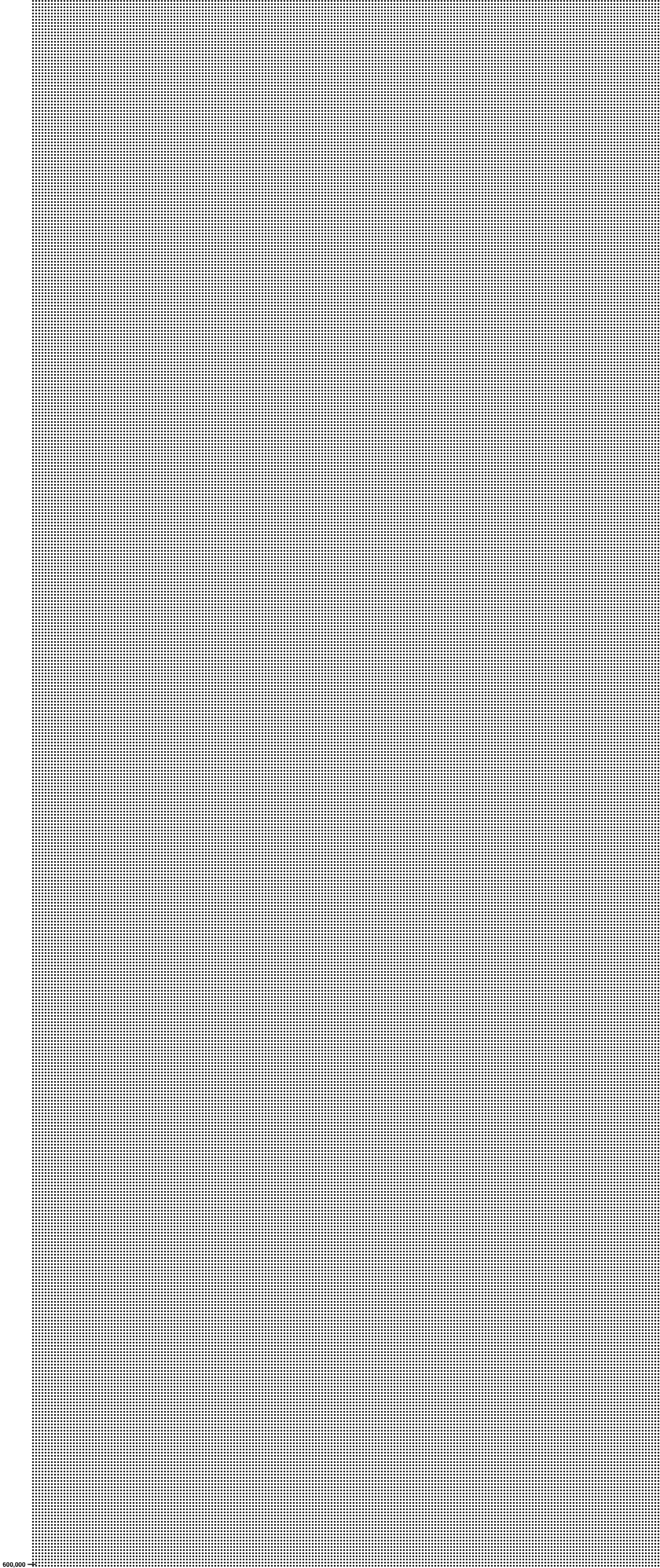

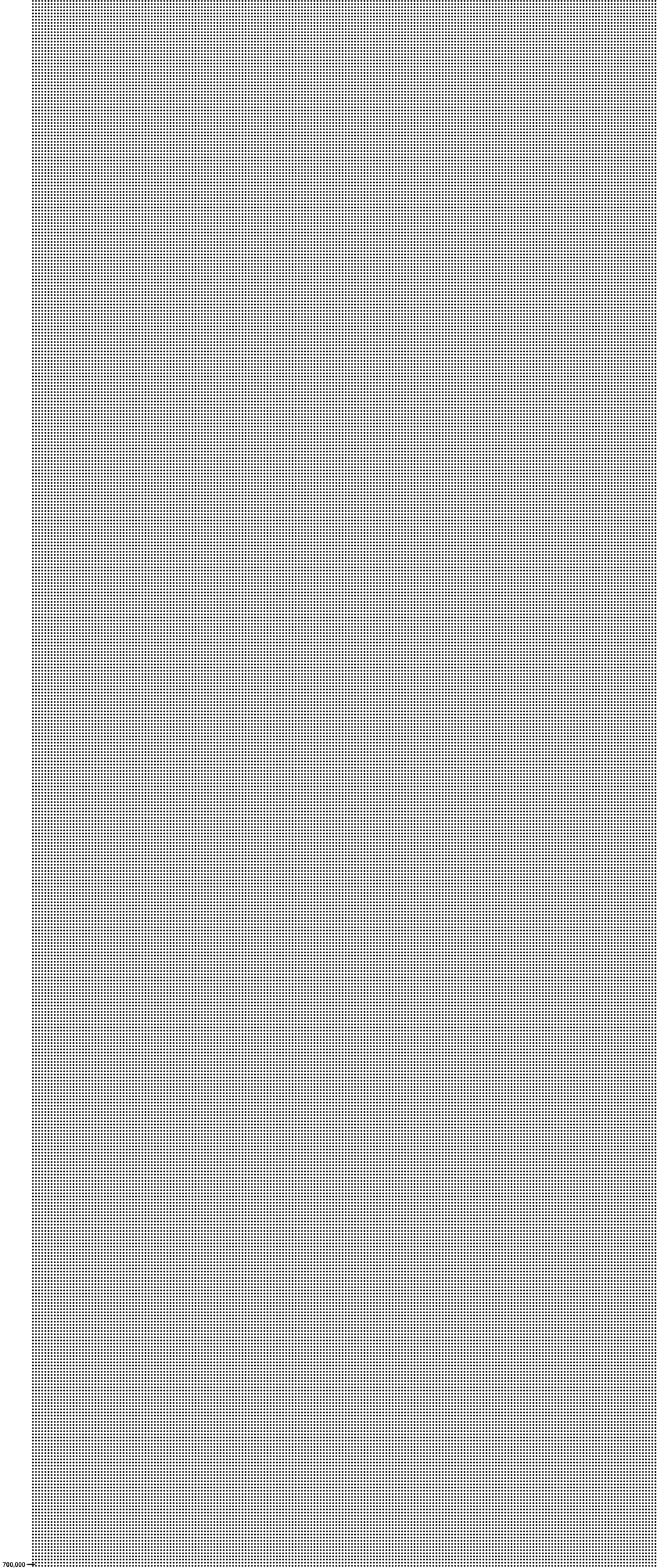

What’s more, even if Noah had somehow been able to fell tens of thousands of massive timber-quality trees, haul all that lumber to a construction site (about 7,400,000 pounds worth), build a 450-foot ark, and ensure that it was perfectly watertight – all by himself, and all at the age of 600 (as Genesis 6 describes) – that still leaves the question of how on earth he could have gathered a pair (or seven) of every single animal in the world and fit them all onto that one boat. After all, 450 feet might be very large for a vessel made of wood, but it’s still pretty small in absolute terms – only about half the size of the Titanic (maximum capacity: 3,547) – and the number of animal species on Earth is literally in the millions. To put that into perspective, below is a picture of one million dots. (Keep in mind, this is only a fraction of the total number of animal species estimated to exist – even the most conservative estimates put the total at several million – but just for simplicity’s sake (and because a lot of them are insects that don’t take up much space), we’ll stick with a measly one million here.) Imagine that each of these dots is a different kind of animal. Now mentally double (or septuple) that image in your mind, since there was supposedly a pair (or seven) of each animal brought onto the ark. And now consider not only that Noah would have had to fit this many animals onto a single boat, but that each of them would have required enough food and fresh water to last them an entire year. Just one pair of those dots – the elephants alone – would have required 300,000 pounds of food and 30,000 gallons of water; two giraffes would require 50,000 pounds of food; two lions would require 15,000 pounds of meat (which, even with the best preservation techniques available at the time, would have gone bad barely a quarter of the way into the voyage); and so forth. On top of all this, each of these animals would have produced a commensurate amount of waste, which would have had to be disposed of somehow. Does it really seem plausible, then, that Noah would have not only been able to fit this many animals and provisions onto a single boat, but that all the necessary food, water, veterinary care, and waste disposal could have been delivered to every one of these animals, every day, for an entire year, by just eight people?

Faced with the obvious logistical impossibilities here, some biblical literalists will try to reconcile them by suggesting that the definition of “two of every kind” might not actually mean two of every species, but two of some broader taxonomic category, like family or order – i.e. two cat-like animals, two dog-like animals, two deer-like animals, etc. So instead of having reindeer and white-tailed deer and Chinese water deer and pudús, you’d just have one pair of reindeer; instead of having gazelles and impalas and oryxes and ibexes, you’d just have one pair of gazelles; and so on. (All the other species would be killed in the flood but would re-emerge later.) But as Mark Isaak points out, that doesn’t seem to fit with what the Bible itself describes:

The Biblical “kind,” according to most interpretations, implies reproductive separateness. On the ark, the purpose of gathering different kinds [in male-female pairs] was to preserve them by later reproduction. Species, by definition, is the level at which animals are reproductively distinct.

In response to this, then, some literalists will say that it wasn’t just that Noah only took one species from each family or order, but that there was only one species of each family or order that even existed back in Noah’s time – so that instead of there being (for instance) lions and tigers and leopards, there would have just been one generic species of proto-cat, from which all modern varieties of cat would eventually descend (and only one species of proto-dog, and only one species of proto-deer, and so on).

But by trying to rationalize that there must have been fewer “kinds” of animals at the time (or that some of them went extinct and re-emerged later), literalists paint themselves into a corner – because by saying that there were originally only a handful of species, they’re also forcing themselves to conclude that the animals, after leaving the ark, must have undergone extraordinarily rapid evolution and speciation in order to account for the existence of the millions of species we know today. And this isn’t just ironic because literalists are so anti-evolution in general – it’s also flatly indefensible in light of everything we know about biology and genetics. There simply wouldn’t have been enough time for such a small handful of species, in a mere couple thousand years, to accumulate enough mutations to account for the vast genetic diversity we see today; animals’ reproductive cycles are just too long for that.

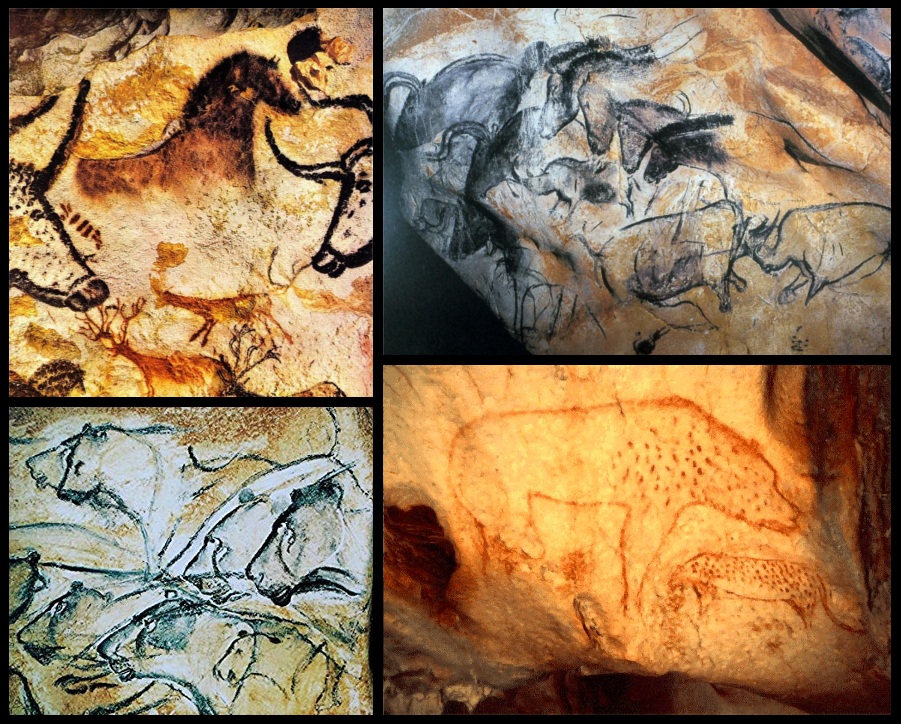

Besides, regardless of biology, the “fewer species” explanation is a non-starter simply because we know from ancient texts, sculptures, and artwork that a wide range of different species of the same “kind” have been here all along – before, during, and after the time frame given for the flood. Cave paintings from 30,000 years ago depict lions, leopards, and other feline species, along with different varieties of horses, deer, bison, and other herd animals; carvings and sculptures from ancient Egypt (pre- and post-flood) depict still more varieties of cats, birds, and other animals; and so on.

So no matter how you frame it, getting all those animals onto the ark still would have presented a logistically unworkable problem, just in terms of sheer numbers. But on top of that, it would have been unworkable in practically every other sense as well. Getting every kind of animal onto the ark would have meant assembling animals from every corner of the planet, most of them separated by thousands of miles. How would the penguins and elephant seals have gotten from Antarctica all the way to the Middle East? How would the koalas and echidnas have gotten there from Australia? How would the sloths and snails of the Amazon have traveled all the way there by foot – a trip that, given how slowly these animals move, would have taken longer than their natural lifespans? How could they have crossed thousands of miles of treeless deserts and saltwater oceans with nothing around to eat or drink? And for that matter, how could these animals have even survived once they actually reached the ark? Arctic species often require a cold environment to survive, desert reptiles require a hot environment, tropical species require a humid environment, and so on. What’s more, a lot of animals can only eat very specific kinds of food found exclusively in their native parts of the world – koalas, for instance, subsist entirely on eucalyptus plants that can only be found in Australia – and if they try to leave those habitats where their food grows, they starve to death. How would these animals have managed? And once they disembarked, how would they have so precisely found their way back to their home habitats, such that all the marsupials would end up back in Australia, all the lemurs would end up in Madagascar, all the species native to the Galapagos Islands would return straight there and nowhere else, and not a single one of these species would leave even the slightest trace of evidence that they had migrated to or from the Middle East (or anywhere else outside their native habitats) during the time frame in question?

There’s also the issue of Noah supposedly taking one male and one female of every species onto the ark. Aside from the fact that this would result in most species becoming so horrendously inbred that they would immediately go extinct (the minimum viable population size for most vertebrates is about 4,000 individuals), there are a number of animal species that don’t even reproduce sexually, so bringing one male and one female wouldn’t even make sense. Several species of lizard, for instance, are all-female and reproduce parthenogenically – so it wouldn’t have been possible to bring one male onto the ark, because males don’t exist. Other species, like earthworms, snails, and slugs, are hermaphroditic – meaning that each individual has both male and female characteristics and can serve either role in reproduction – so again, it wouldn’t have been possible for Noah to collect one male and one female of each of these species, because different sexes don’t exist for them.

Similarly, there’s the question of eusocial species like bees, ants, and termites, for whom just having one queen and one male drone wouldn’t constitute a viable hive or colony; those species need the entire nest to survive. And speaking of invertebrates, what about those species with extremely short lifespans? As Isaak points out, “Adult mayflies on the ark would have died in a few days, and the larvae of many mayflies require shallow fresh running water. Many other insects would face similar problems.”

We haven’t even mentioned all the world’s aquatic species, which would face some of the biggest problems of all. If the whole world flooded, then all the salt water would mix with all the fresh water, and the result would be a brackish mixture in which most fish would be unable to survive. Aside from a few rare species that can withstand rapid changes in salinity, freshwater fish can’t tolerate salt water, and saltwater fish can’t tolerate fresh water. The Bible doesn’t seem at all concerned with the survival of these species; it seems the authors of Genesis either assumed that they’d be fine in any kind of water, or they simply failed to account for them. But if Noah’s flood had actually happened, the aquatic animals would have met the same fate as those still on land – mass eradication.

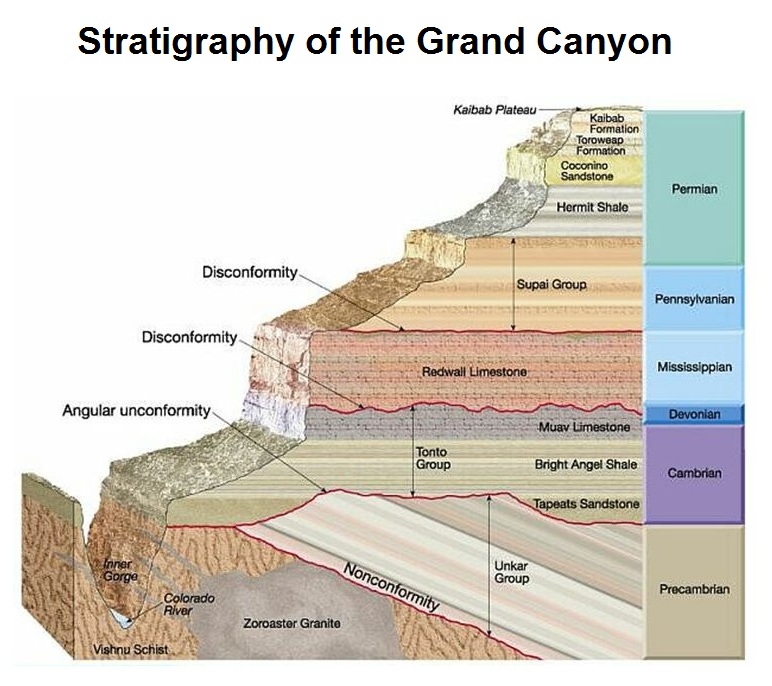

And this leads to one of the biggest problems of all with the flood story: the fact that it leaves no room for any life outside of the ark to have survived the deluge. Genesis 6:17, 7:4, and 7:23 all make it exceptionally clear that “every living substance” outside the ark was utterly destroyed, with no survivors of any species. If that was the case, though, then what would have happened once the animals that were on the ark finally disembarked and went out into the world again? There would have been nothing but ravaged wasteland stretching across the entire globe – so what, for instance, would the carnivores have eaten? Would they have just eaten all the herbivores that had just gotten off the ark, and then turned on each other once they ran out of those? The herbivores themselves wouldn’t have been any better off in terms of food supply; if the world really had been underwater for an entire year, with the water level reaching five and a half miles high (high enough to cover even the highest mountains, as the Bible claims), plant life would have been utterly wiped out. In theory, it might have been possible for the seeds of a few coastal species like mangroves and coconuts to survive a year-long global flood, but that wouldn’t have counted for much if every other living substance on Earth truly was destroyed. And it certainly would have been – not only would the extreme turbulence, high salinity of the water, and avalanches of sediment have killed and buried all the plants on Earth (not to mention ruining the soil), the sheer depth of the waters would have made it impossible for any life-sustaining sunlight to reach them even if they somehow did survive everything else. In fact, as Charles Templeton points out, if there had been enough water “to cover the entire globe to a height more than five and a half miles high, the weight of it would [have collapsed] the surface of the earth.”

The biblical authors couldn’t have known all this, of course – which is why Genesis 8:10 describes Noah sending out a dove after the floodwaters recede and having it return to him with an olive leaf in its beak, as if there wasn’t even an issue. The authors had probably experienced plenty of small local floods before in which the trees and bushes had survived just fine – so why should a global mega-flood be any different? There would have been no reason for them to think that the world’s olive trees couldn’t have survived the flood perfectly intact. But for us who know better, this plot hole requires an actual explanation – as do all the other plot holes in the flood story (including many that we haven’t even mentioned here, like how anyone aboard the ark could have survived at all at an altitude of five and a half miles, where the air is too thin to be survivable for more than a day or two).

In light of all these problems, then, a lot of biblical literalists will just bite the bullet and admit that there’s no practical way these things could have all been accomplished by normal means – but then they’ll add that no practical explanation is necessary anyway, because God could have just performed miracles to solve all these problems. The way that all the animals could have gotten to the ark is that God could have just miraculously transported them there; the way that they could have all fit on board is that God could have just miraculously expanded the ark’s interior dimensions; the way they could have survived the voyage is that God could have miraculously sustained them; and so on. But if you’re just going to hand-wave away every problem in the story by saying that God could have solved it with miracles, then what would have been the point of flooding the earth in the first place? Why bother with the whole ordeal of gathering every animal species onto a boat, causing it to rain for 40 days, waiting for the floodwaters to dry up, and so on, when God could have just as easily snapped his fingers and miraculously caused all the evil people in the world to instantly vanish, accomplishing the same goal without any fuss?