I – II – III – IV – V – VI – VII – VIII – IX – X – XI – XII – XIII – XIV – XV – XVI – XVII – XVIII – XIX – XX – XXI – XXII – XXIII – XXIV – XXV – XXVI – XXVII

[Single-page view]

Of course, sometimes it will turn out that the regulations put in place to keep the market safe are too weak, and some kind of worst-case disaster scenario will actually occur; things will spiral out of control to such an extent that instead of being able to keep market failures in check just by using basic preventative measures (as in the case of air pollution, where it’s fairly straightforward to simply notice when too much pollution is being emitted and introduce regulation as needed to cut it back down again), mere preventative measures alone will no longer be enough to resolve the issue, because there will be some kind of acute mass-scale crisis that demands a more immediate response. One of the best examples of this was the 2008 financial crisis, in which a collapse in the banking sector threatened to bring down the entire economy. The seeds of the crisis were first planted when some of the big banks figured out how to take a bunch of the subprime mortgages they had on their books – i.e. mortgages that were more likely than normal to default – and bundle them together into financial products, which they then inaccurately labeled as extremely low-risk and sold off to oblivious buyers (including ordinary investors as well as other big financial institutions). When those supposedly safe investments turned out to be worthless, everyone who’d bought them suddenly found themselves suffering major losses they hadn’t planned for – and as a result, they had to tighten their belts in other areas to compensate for those losses. Lenders were no longer able to lend as much, and it became more difficult for individuals and firms to buy things on credit, so business began to slow down – and with business slowing down, firms were forced to cut labor costs by laying off employees or reducing their hours. This reduction in income for employees meant a reduction in consumer spending, as ordinary workers now had less spending money – and this reduction in consumer spending, naturally, meant even less revenue for businesses, which led to further layoffs, and so on in a self-reinforcing cycle, until ultimately the entire economy had ground to a halt.

So what can be done in a situation like this, in which the private sector has gotten itself stuck in a rut with no immediate way of pulling itself out? This is yet another area where the public sector can help offset the private sector’s failings by taking countermeasures of its own to balance them out. And it can do this in a few different ways. Among other things, it can provide backstops to prevent the failure of one bank from triggering a contagion of bank runs that brings down the whole banking system (not just with bailouts, but with basic guardrails like public deposit insurance and the like). It can use its tools of monetary policy to adjust interest rates as needed to loosen up credit markets and make it easier for private-sector actors to make big purchases and investments. And if even rock-bottom interest rates aren’t enough to get the market moving again, it can take an even more direct approach and increase its own spending and/or decrease taxation so as to put money back in people’s pockets and reverse the feedback loop of economic contraction.

Let’s discuss each of these approaches briefly, starting with the first one – providing backstops to prevent bank failures from spreading. As Heath explains, back in the days before federal deposit insurance, the threat of contagious bank runs was a major problem, and it led to frequent recessions that were both incredibly disruptive and wholly unnecessary – but once the FDIC was introduced, it essentially resolved the issue (at least for traditional banks) in one fell swoop:

During the Golden Age of laissez-faire capitalism, recessions were often preceded by bank failures. Because banks lend out most of the money that they receive, they cannot actually repay more than a small fraction of depositors at a time. […] This has the potential to spark a bank run—a collective action problem in which depositors, convinced that the bank is going to fail, try to get their money out before the bank does, yet, in so doing, essentially guarantee that the bank will fail.

While this may be tough luck for the bank’s customers, it is not necessarily a problem for the economy as a whole. Furthermore, it is not clear why it should cause a recession. Keynes’s analysis, however, provides a very simple explanation. It is the way the other banks responded that created general problems. As soon as one bank failed, all the other banks immediately tried to increase their cash reserves in order to protect themselves against the impact of copycat withdrawals and the possibility of a generalized bank panic. Furthermore, customers would get antsy about making deposits, and so would begin holding on to their money. The result was often a huge overnight shift in liquidity preference, with everyone suddenly wanting to hold as much physical currency as possible. This led to a systemic slackening of economic activity in all other sectors, as people became loath to engage in transactions, preferring to hold on to their money.

[…]

Public deposit insurance, one of the most important social programs for capitalists, essentially eliminated the problem of runs on ordinary commercial banks. (This is one of the reasons why the financial crisis of 2008 occurred in what some called the “parallel” banking sector—financial institutions that were operating outside the scope of government regulatory programs, including federal deposit insurance.) Stabilizing the banks had significant stabilizing effects on the business cycle (a fact that Marxian “crisis” theory is unable to explain). Recessions became less common and less severe, simply because one of the primary sources of volatility in the demand for money had been eliminated.

As he rightly points out, despite the stabilizing effect of public deposit insurance on the traditional banking sector, it’s still possible nowadays to have recessions that are caused by things other than classic bank runs. So what can be done when such recessions do occur? That’s when the government can turn to the next tool in its toolbox, monetary policy – lowering interest rates, boosting market liquidity, and expanding the supply of money circulating throughout the economy. This kind of intervention isn’t usually necessary under normal circumstances, since interest rates will tend to naturally adjust to market conditions and counteract routine slumps on their own, as Wheelan explains:

In a weak economy, interest rates typically fall because there is less demand for credit; struggling businesses and households are less inclined to borrow for an expansion or a bigger house. However, falling interest rates create a natural antidote for modest economic downturns. As credit gets cheaper, households are induced to buy more big-ticket items—cars and washing machines and even homes. Meanwhile, businesses find it cheaper to expand and invest. These new investments and purchases help restore the economy to health.

Occasionally, though, lenders might not be able to provide enough cheap credit to fully reverse the slump because they’ll have too much of their money wrapped up in non-loanable assets like bonds and not enough in the form of loanable funds. In such cases, then, the Federal Reserve (America’s central bank) will be able to help out by buying up those bonds so the banks have enough loanable cash to lower their interest rates still further. It’s not really necessary for our purposes here to understand all the logistical details of how this works – just that this is something the Fed can do – but if you’re interested, Wheelan provides a basic overview of the process:

Where does the Fed derive this extraordinary power over interest rates? After all, commercial banks are private entities. The Federal Reserve cannot force Citibank to raise or lower the rates it charges consumers for auto loans and home mortgages. Rather, the process is indirect. [See,] the interest rate is really just a rental rate for capital, or the “price of money.” The Fed controls America’s money supply. We’ll get to the mechanics of that process in a moment. For now, recognize that capital is no different from apartments: The greater the supply, the cheaper the rent. The Fed moves interest rates by making changes in the quantity of funds available to commercial banks. If banks are awash with money, then interest rates must be relatively low to attract borrowers for all the available funds. When capital is scarce, the opposite will be true: Banks can charge higher interest rates and still attract enough borrowers for all available funds. It’s supply and demand, with the Fed controlling the supply.

These monetary decisions—the determination whether interest rates need to go up, down, or stay the same—are made by a committee within the Fed called the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), which consists of the board of governors, the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, and the presidents of four other Federal Reserve Banks on a rotating basis. The Fed chairman is also the chairman of the FOMC. Ben Bernanke [the Fed chairman during the post-2008 recession, when this was written] derives his power from the fact that he is sitting at the head of the table when the FOMC makes interest rate decisions.

If the FOMC wants to stimulate the economy by lowering the cost of borrowing, the committee has two primary tools at its disposal. The first is the discount rate, which is the interest rate at which commercial banks can borrow funds directly from the Federal Reserve. The relationship between the discount rate and the cost of borrowing at Citibank is straightforward; when the discount rate falls, banks can borrow more cheaply from the Fed and therefore lend more cheaply to their customers. There is one complication. Borrowing directly from the Fed carries a certain stigma; it implies that a bank was not able to raise funds privately. Thus, turning to the Fed for a loan is similar to borrowing from your parents after about age twenty-five: You’ll get the money, but it’s better to look somewhere else first.

Instead, banks generally borrow from other banks. The second important tool in the Fed’s money supply kit is the federal funds rate, the rate that banks charge other banks for short-term loans. The Fed cannot stipulate the rate at which Wells Fargo lends money to Citigroup. Rather, the FOMC sets a target for the federal funds rate, say 4.5 percent, and then manipulates the money supply to accomplish its objective. If the supply of funds goes up, then banks will have to drop their prices—lower interest rates—to find borrowers for the new funds. One can think of the money supply as a furnace with the federal funds rate as its thermostat. If the FOMC cuts the target fed funds rate from 4.5 percent to 4.25 percent, then the Federal Reserve will pump money into the banking system until the rate Wells Fargo charges Citigroup for an overnight loan falls to something very close to 4.25 percent.

All of which brings us to our final conundrum: How does the Federal Reserve inject money into a private banking system? Does Ben Bernanke print $100 million of new money, load it into a heavily armored truck, and drive it to a Citibank branch? Not exactly—though that image is not a bad way to understand what does happen.

Ben Bernanke and the FOMC do create new money. In the United States, they alone have that power. (The Treasury merely mints new currency and coins to replace money that already exists.) The Federal Reserve does deliver new money to banks like Citibank. But the Fed does not give funds to the bank; it trades the new money for government bonds that the banks currently own. In our metaphorical example, the Citibank branch manager meets Ben Bernanke’s armored truck outside the bank, loads $100 million of new money into the bank’s vault, and then hands the Fed chairman $100 million in government bonds from the bank’s portfolio in return. Note that Citibank has not been made richer by the transaction. The bank has merely swapped $100 million of one kind of asset (bonds) for $100 million of a different kind of asset (cash, or, more accurately, its electronic equivalent).

Banks hold bonds for the same reason individual investors do; bonds are a safe place to park funds that aren’t needed for something else. Specifically, banks buy bonds with depositors’ funds that are not being loaned out. To the economy, the fact that Citibank has swapped bonds for cash makes all the difference. When a bank has $100 million of deposits parked in bonds, those funds are not being loaned out. They are not financing houses, or businesses, or new plants. But after Ben Bernanke’s metaphorical armored truck pulls away, Citibank is left holding funds that can be loaned out. That means new loans for all the kinds of things that generate economic activity. Indeed, money injected into the banking system has a cascading effect. A bank that swaps bonds for money from the Fed keeps some fraction of the funds in reserves, as required by law, and then loans out the rest. Whoever receives those loans will spend them somewhere, perhaps at a car dealership or a department store. That money eventually ends up in other banks, which will keep some funds in reserve and then make loans of their own. A move by the Fed to inject $100 million of new funds into the banking system may ultimately increase the money supply by 10 times as much.

Of course, the Fed chairman does not actually drive a truck to a Citibank branch to swap cash for bonds. The FOMC can accomplish the same thing using the bond market (which works just like the stock market, except that bonds are bought and sold). Bond traders working on behalf of the Fed buy bonds from commercial banks and pay for them with newly created money—funds that simply did not exist twenty minutes earlier. (Presumably the banks selling their bonds will be those with the most opportunities to make new loans.) The Fed will continue to buy bonds with new money, a process called open market operations, until the target federal funds rate has been reached.

Obviously what the Fed giveth, the Fed can take away. The Federal Reserve can raise interest rates by doing the opposite of everything we’ve just discussed. The FOMC would vote to raise the discount rate and/or the target fed funds rate and issue an order to sell bonds from its portfolio to commercial banks. As banks give up lendable funds in exchange for bonds, the money supply shrinks. Money that might have been loaned out to consumers and businesses is parked in bonds instead. Interest rates go up, and anything purchased with borrowed capital becomes more expensive. The cumulative effect is slower economic growth.

That last point is important to note; in addition to lowering interest rates when the economy is slumping, the Fed can also raise them if the economy seems to be overheating. If demand is starting to significantly outpace supply, and it’s driving up prices to such a degree that the threat of out-of-control inflation starts to become a real danger, the Fed can take some of the air out of the system by tightening the credit market back up again. Wheelan continues:

The [Federal Reserve’s] job would not appear to be that complicated. If the Fed can make the economy grow faster by lowering interest rates, then presumably lower interest rates are always better. Indeed, why should there be any limit to the rate at which the economy can grow? If we begin to spend more freely when rates are cut from 7 percent to 5 percent, why stop there? If there are still people without jobs and others without new cars, then let’s press on to 3 percent, or even 1 percent. New money for everyone! Sadly, there are limits to how fast any economy can grow. If low interest rates, or “easy money,” causes consumers to demand 5 percent more new PT Cruisers than they purchased last year, then Chrysler must expand production by 5 percent. That means hiring more workers and buying more steel, glass, electrical components, etc. At some point, it becomes difficult or impossible for Chrysler to find these new inputs, particularly qualified workers. At that point, the company simply cannot make enough PT Cruisers to satisfy consumer demand; instead, the company begins to raise prices. Meanwhile, autoworkers recognize that Chrysler is desperate for labor, and the union demands higher wages.

The story does not stop there. The same thing would be happening throughout the economy, not just at Chrysler. If interest rates are exceptionally low, firms will borrow to invest in new computer systems and software; consumers will break out their VISA cards for big-screen televisions and Caribbean cruises—all up to a point. When the cruise ships are full and Dell is selling every computer it can produce, then those firms will raise their prices, too. (When demand exceeds supply, firms can charge more and still fill every boat or sell every computer.) In short, an “easy money” policy at the Fed can cause consumers to demand more than the economy can produce. The only way to ration that excess demand is with higher prices. The result is inflation.

The sticker price on the PT Cruiser goes up, and no one is better off for it. True, Chrysler is taking in more money, but it is also paying more to its suppliers and workers. Those workers are seeing higher wages, but they are also paying higher prices for their basic needs. Numbers are changing everywhere, but the productive capacity of our economy and the measure of our well-being, real GDP, has hit the wall. Once started, the inflationary cycle is hard to break. Firms and workers everywhere begin to expect continually rising prices (which, in turn, causes continually rising prices). Welcome to the 1970s.

The pace at which the economy can grow without causing inflation might reasonably be considered a “speed limit.” After all, there are only a handful of ways to increase the amount that we as a nation can produce. We can work longer hours. We can add new workers, through falling unemployment or immigration (recognizing that the workers available may not have the skills in demand). We can add machines and other kinds of capital that help us to produce things. Or we can become more productive—produce more with what we already have, perhaps because of an innovation or a technological change. Each of these sources of growth has natural constraints. Workers are scarce; capital is scarce; technological change proceeds at a finite and unpredictable pace. In the late 1990s, American autoworkers threatened to go on strike because they were being forced to work too much overtime. (Don’t we wish we had that problem now…) Meanwhile, fast-food restaurants were offering signing bonuses to new employees. We were at the wall. Economists reckon that the speed limit of the American economy is somewhere in the range of 3 percent growth per year.

The phrase “somewhere in the range” gives you the first inkling of how hard the Fed’s job is. The Federal Reserve must strike a delicate balance. If the economy grows more slowly than it is capable of, then we are wasting economic potential. Plants that make PT Cruisers sit idle; the workers who might have jobs there are unemployed instead. An economy that has the capacity to grow at 3 percent instead limps along at 1.5 percent, or even slips into recession. Thus, the Fed must feed enough credit to the economy to create jobs and prosperity but not so much that the economy begins to overheat. William McChesney Martin, Jr., Federal Reserve chairman during the 1950s and 1960s, once noted that the Fed’s job is to take away the punch bowl just as the party gets going.

Or sometimes the Fed must rein in the party long after it has gone out of control. The Federal Reserve has deliberately engineered a number of recessions in order to squeeze inflation out of the system. Most notably, Fed chairman Paul Volcker was the ogre who ended the inflationary party of the 1970s. At that point, naked people were dancing wildly on the tables. Inflation had climbed from 3 percent in 1972 to 13.5 percent in 1980. Mr. Volcker hit the monetary brakes, meaning that he cranked up interest rates to slow the economy down. Short-term interest rates peaked at over 16 percent in 1981. The result was a painful unwinding of the inflationary cycle. With interest rates in double digits, there were plenty of unsold Chrysler K cars sitting on the lot. Dealers were forced to cut prices (or stop raising them). The auto companies idled plants and laid off workers. The autoworkers who still had jobs decided that it would be a bad time to ask for more money.

The same thing, of course, was going on in every other sector of the economy. Slowly, and at great human cost, the expectation that prices would steadily rise was purged from the system. The result was the recession of 1981–1982, during which GDP shrank by 3 percent and unemployment climbed to nearly 10 percent. In the end, Mr. Volcker did clear the dancers off the tables. By 1983, inflation had fallen to 3 percent. Obviously it would have been easier and less painful if the party had never gone out of control in the first place.

Fortunately (even though the process can be painful), inflation is something that generally responds to monetary policy in a straightforward way, so central bankers can be fairly confident in their ability to rein it in if it starts getting too extreme. If it doesn’t seem to be responding to their interest rate hikes at first, they can just keep raising interest rates until it does. The flip side of this, though, is that despite there being no limit to how much interest rates can be raised, there is a limit to how much they can be lowered – it’s not possible to go below zero – so if the problem the Fed is facing isn’t inflation, but the opposite problem of recession and unemployment, the solution might be a bit more complicated than just adjusting interest rates and letting the market do the rest. To be sure, that kind of solution can work perfectly well for relatively minor slumps, in which lenders can still find new lending opportunities if they’re just given more loanable funds and their interest rates are lowered enough to attract new borrowers. But if there’s an especially severe recession, simply lowering interest rates – even lowering them to near-zero – might not be enough, because those kinds of safe lending opportunities won’t be as abundant anymore; so even if lenders have plenty of loanable cash on hand, they might not want to loan any of it out – and as a consequence, the economy will remain stuck. As Taylor writes:

Monetary policy might be better at contracting an economy than at stimulating it. Just as you can lead a horse to water but can’t make it drink, a central bank can buy bonds from banks so banks have more money to lend, but it can’t force banks to lend that additional money. If banks are unwilling to lend because they’re afraid of too many defaults, monetary policy won’t be much help in fighting a recession. In the aftermath of the 2007–2009 recession, banks and many nonfinancial firms were holding substantial amounts of cash, but given the level of economic uncertainty, they were reluctant to make loans. Central bankers have an old saying to capture this problem: Monetary policy can be like pulling and pushing on a string. When you pull a string, it moves toward you, but when you push on a string, it folds up and doesn’t move. When a central bank pulls on the string through contractionary policy, it can definitely raise interest rates and reduce aggregate demand. But when a central bank tries to push on the string through expansionary policy, it won’t have any effect if banks decide not to lend. It’s not that expansionary monetary policy never works, but it’s not always reliable.

Keynes had another memorable analogy for this:

Some people seem to infer […] that output and income can be raised by increasing the quantity of money. But this is like trying to get fat by buying a larger belt. In the United States to-day your belt is plenty big enough for your belly. It is a most misleading thing to stress the quantity of money, which is only a limiting factor, rather than the volume of expenditure, which is the operative factor.

If monetary policy alone isn’t sufficient to restore the amount of spending in the economy to normal levels, then, a more direct form of stimulus may be needed. As Krugman (writing in 2009) explains:

During a normal recession, the Fed responds by buying Treasury bills — short-term government debt — from banks. This drives interest rates on government debt down; investors seeking a higher rate of return move into other assets, driving other interest rates down as well; and normally these lower interest rates eventually lead to an economic bounceback. The Fed dealt with the recession that began in 1990 by driving short-term interest rates from 9 percent down to 3 percent. It dealt with the recession that began in 2001 by driving rates from 6.5 percent to 1 percent. And it tried to deal with the current recession by driving rates down from 5.25 percent to zero.

But zero, it turned out, isn’t low enough to end this recession. And the Fed can’t push rates below zero, since at near-zero rates investors simply hoard cash rather than lending it out. So by late 2008, with interest rates basically at what macroeconomists call the “zero lower bound” even as the recession continued to deepen, conventional monetary policy had lost all traction.

Now what? This is the second time America has been up against the zero lower bound, the previous occasion being the Great Depression. And it was precisely the observation that there’s a lower bound to interest rates that led Keynes to advocate higher government spending: when monetary policy is ineffective and the private sector can’t be persuaded to spend more, the public sector must take its place in supporting the economy. Fiscal stimulus is the Keynesian answer to the kind of depression-type economic situation we’re currently in.

This is the final way in which government can intervene to rescue the private sector from recession. Unlike monetary policy, which involves the central bank adjusting the money supply and changing interest rates in order to affect the private sector’s spending levels, fiscal policy is about the spending that the government directly does itself. And in the case of an extreme recession that has hamstrung the private sector’s ability to spend enough money to restore the economy to full health, the public sector can be justified in picking up the slack by doing more spending than usual on its own part. As Krugman writes:

When almost everyone is the world is trying to spend less than their income, the result is a vicious contraction—because my spending is your income, and your spending is my income. What you need to limit the damage is for somebody to be willing to spend more than their income. And governments [can play] that crucial role.

Or as Heath puts it:

Recessions occur when there is a sudden change in liquidity preference, leading to a shortage of money in circulation. One way to address this is to increase the money supply […] or to lower interest rates. Keynes, however, thought that there were limits on the effectiveness of either strategy. As a result, if people weren’t willing to spend their own money, the next-best solution was for the government to spend it for them. Keynes recommended that the state engage in “countercyclical spending”—running a surplus [or at least running a relatively tighter budget] in times of economic expansion, then [being more willing to engage in] deficit-spending during recessions.

Taylor goes into a bit more detail about how exactly this strategy works, and how to some extent it can be set up to kick in automatically whenever it’s needed rather than requiring government to respond to every market fluctuation on a case-by-case basis:

A policy of increasing aggregate demand or buying power in the economy is called expansionary macroeconomic policy. It’s also sometimes called a “loose” fiscal policy. Expansionary policy includes tax cuts and spending increases, for example, both of which put more money into the economy. Policies used to reduce aggregate demand, in contrast, are called contractionary policies, or “tight” fiscal policies. A policy of tax increases or spending cuts is considered contractionary, reducing the amount of buying power in the economy. Such a policy can also be used to lean against the cycles of the economy; such countercyclical fiscal policy aims at counterbalancing the underlying economic cycle of recession and recovery.

The decision about whether to use changes in spending or in taxes to affect demand will depend on specific conditions of that time and place and on political priorities. The emphasis is to get the economy moving, one way or another, by pumping up aggregate demand. In his General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, John Maynard Keynes (1936) ruminates at one point that the government could “fill old bottles with bank notes and bury them at a suitable depth in disused coal mines, which were then filled up to the surface with town rubbish, and leave it to private enterprise on the well-tried principles of laissez-faire to dig the notes up again.” He also points out that it would be more sensible to stimulate the economy in a way that provided actual economic benefits—his example is building houses—but his point is that when you’re trying to pump up aggregate demand, exactly how you do it is a secondary concern from a macroeconomic point of view.

If, instead of fighting unemployment, we’re trying to fight inflation, we need to think about a tight fiscal policy to reduce aggregate demand. This means lowering spending and/or raising taxes, and the theory doesn’t dictate which choice or which mix of the two is best for any given situation or in general.

[…]

Countercyclical fiscal policy can be implemented in two ways: automatic and discretionary. Automatic stabilizers are government fiscal policies that, without any need for legislation, automatically stimulate aggregate demand when the economy is declining and automatically hold down aggregate demand when the economy is expanding.

To understand how this happens automatically, imagine first that the economy is growing rapidly. Aggregate demand is very high; it’s at or above potential GDP, and we’re worried about inflation. What would be the appropriate countercyclical fiscal policy in this situation? One option is to increase taxes to take some of the buying power out of the economy. But this happens automatically to some extent because taxes are, more or less, a percentage of what people earn. As income rises, taxes therefore automatically rise. Indeed, the U.S. individual income tax is structured around tax brackets so as people earn more income, the taxes paid out of each additional dollar gradually rise. The same process works in reverse, of course. In a shrinking economy, the taxes that people owe automatically decline because taxes are a share of income. This helps prevent aggregate demand from shrinking as much as it otherwise would. Thus, taxes are an automatic countercyclical fiscal policy, or an automatic stabilizer.

On the spending side, when the economy grows, what countercyclical policy do we want to apply, and what actually happens? As a booming economy approaches potential GDP, the goal of countercyclical fiscal policy is to prevent demand from growing too fast and tipping the economy into inflation. But when the economy is doing well, fewer people need government support programs such as welfare, Medicaid, and unemployment benefits. As a result, in good economic times, spending from the government in these kinds of categories automatically declines, which acts as the desired automatic stabilizer. The same works in reverse. In a shrinking economy or a recession, more people are unemployed and need government assistance. At such times, government spending on programs that help the unemployed and the poor tends to rise, boosting aggregate demand (or at least keeping it from shrinking too much), which is exactly the countercyclical fiscal policy one would want.

Recent economic experience offers several examples of these patterns. During the dot-com economic boom of the late 1990s, there was an unexpected surge in federal tax revenues. President Bill Clinton’s proposed budget for fiscal year 1998 predicted a deficit of $120 billion, but when the booming economy produced $200 billion more in tax revenue than expected, it led to a budget surplus of $69 billion. Similarly, Clinton’s proposed budget for 1999 predicted a balanced budget in 2000; they actually got a surplus of $236 billion. Surpluses that existed between 1998 and 2001 led to increased federal tax revenues; federal taxes in 2000 collected 20.9 percent of GDP. These unexpectedly high tax revenues weren’t the result of new legislation. They were automatic stabilizers, helping to prevent the economy from expanding too quickly and triggering inflation.

As a counterexample, consider the extremely large budget deficits of 2009 and 2010. President George W. Bush’s last proposed budget, which applied to fiscal year 2009, projected that the tax revenues for 2009 would be 18 percent of GDP. But when the recession hit, tax revenues for 2009 turned out to be just 14.8 percent of GDP. A portion of this drop was due to tax cuts passed in 2009 under the incoming administration of President Obama, but most of it was due to the recession turning out to be far harsher than expected. This unexpected drop in tax collections was an automatic stabilizer that helped to cushion the blow of the recession.

More broadly, systematic evidence shows the impact of countercyclical fiscal policy over time. John Taylor looked at evidence from the 1960s up through 2000 and found that, on average, a 2 percent fall in GDP led to an automatic offsetting increase in fiscal policy of 1 percent of GDP.

Of course, as you can tell from these numbers, automatic stabilizers aren’t designed to always perfectly offset every swing in the economy all by themselves – so if there’s a really extreme recession, they won’t typically be enough to fully counteract it on their own. This, then, is where discretionary fiscal policy can come into the picture; if private individuals and firms can’t or won’t start spending until they have a little more money in their pockets, government can make that happen by either giving them tax breaks, buying more goods and services from them, or hiring them directly to work on big public works projects – building roads and bridges, rehabilitating dilapidated schools and libraries, and so on – or some combination of things like these. By boosting people’s incomes in this way, government stimulus can enable them to return to more normal levels of spending – and with this increase in consumer demand, private businesses will naturally respond by expanding their operations and hiring more workers, thereby putting even more money in people’s pockets, and causing consumer spending to rise further still, and so on in a virtuous cycle, until ultimately the downward spiral of recession is completely reversed. With the economy back on track, the government can then let the private sector take the lead again, and can allow its own spending to return to more normal levels. This was how the US finally overcame the Great Depression; the government hired millions of unemployed workers and put their unused labor to good use, first with the public works projects of Roosevelt’s New Deal, and then with the ultimate public works project known as World War II. And it used the same kind of fiscal stimulus strategy to pull out of the 2008 recession and other post-war recessions as well, albeit to a much less dramatic degree. You might argue that in each of these cases, the economy could have eventually recovered on its own without government intervention – but as Taylor writes:

Keynesians are concerned that the macroeconomy can become stuck below potential GDP for a long time. Even if the economy gradually returns to full employment in the long run without government action, as Keynes famously wrote, “In the long run, we’re all dead.” Waiting for the long run has large costs; if the economy takes years to readjust, that’s a huge chunk out of people’s lives and careers. Thus, Keynesian economists tend to support active government macroeconomic policies with the goals of fighting unemployment, stimulating the economy, and shortening recessions and depressions as much as possible.

If an active fiscal policy can get the economy back on track more quickly and painlessly than a policy of non-intervention, there’s no reason to prolong people’s hardship by forcing them to endure years of needless financial devastation and all the damage that comes with it. Far better to have a government that can swiftly identify economic problems as they arise and can accordingly adjust its own spending so as to neutralize them before they ever have a chance to cause long-term issues in the first place. There are, after all, always public needs that can be fulfilled – and if the government is able to rescue a foundering economy by employing otherwise idle labor to fulfill them, that’s a win-win for everyone involved. In fact, the benefits of this strategy are so evident that some commentators have proposed making it a more systematic part of the standard operating procedure for national governments, much like automatic stabilizers, which can simply kick in without any fuss whenever there’s a big enough recession. Wheelan, for instance, proposes that the federal government maintain an ongoing list of “deferred maintenance” projects that need doing (but haven’t made it into any federal budgets yet), which it can just pull up and start working on whenever the need for a bit of extra government spending arises:

A successful society needs to move people, goods, and information. Individuals cannot build their own air traffic control systems. Private firms do not have the power of eminent domain to create new corridors for moving freight and information.

Our nation needs an infrastructure strategy that lays out the most important federal infrastructure goals (e.g., reducing traffic congestion, improving air quality, promoting Internet connectivity, etc.) and then creates a mechanism for evaluating all federal projects against those goals. The most cost-effective projects should be included in the infrastructure budget; the projects that do not meet some threshold for cost-effectiveness should be rejected.

Earmarks, the process by which individual legislators tuck their pet projects into larger bills, will not disappear entirely. Congress has the power to pass legislation, including legislation that spends money on stupid things. However, an objective set of criteria for evaluating transportation projects would quantify the silliness of these pet projects. If modernizing the nation’s air traffic control system scores 91 out of 100 when it is evaluated against federal transportation goals, and expanding the parking lot at the Lawn Darts Hall of Fame scores a 3, then it becomes all the more shameful to spend money on the latter. And when shame does not work, a presidential veto just might.

This basic approach has two major advantages. First, it can help restore public trust in the government’s ability to make sensible infrastructure investments—rather than allowing “bridges to nowhere” to be built because an influential legislator was able to slip an earmark into the transportation bill. Second, it provides a less controversial and more efficient form of “stimulus” during economic downturns. Once the federal government has an infrastructure plan made up of approved projects, it is possible to reach deeper into that list of “shovel-ready projects” during slack economic times. There is no money wasted on stimulus spending; sensible spending is merely speeded up.

Other commentators have proposed taking this approach even further and simply making it an official policy that such government-sponsored jobs always be made available to workers whenever the private sector is unable to provide full employment – a so-called “federal job guarantee.” (This is yet another topic that merits an entire post of its own at some point.) Meanwhile, still others come at the issue from the opposite angle and argue that in the case of short-term economic shocks, it may not be necessary for the government to have to create new jobs for people at all, and that it can instead just assume part of the cost of keeping them in their current private-sector jobs. The German Kurzarbeit program, for instance, is designed to do exactly this:

Kurzarbeit is the German name for a program of state wage subsidies in which private-sector employees agree to or are forced to accept a reduction in working hours and pay, with public subsidies making up for all or part of the lost wages.

Several Central European countries use such subsidies to limit the impact on the economy as a whole or a particular sector from short-term threats such as a recession, pandemic, or natural disaster. The idea is to temporarily subsidize companies to avoid layoffs or bankruptcies during a temporary external disruption. Most notably, such subsidy programs were used to offset the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and recession starting in 2020.

These different approaches all have points in their favor. One thing they all have in common, though, is that they all require an increase in government spending. For this reason, conservatives will often object to them on principle, insisting that the responsible thing to do in a recession is not to spend money like drunken sailors, but to “tighten our belts” and cut back on our spending – practicing a strategy of “fiscal austerity.” They’ll be especially opposed to the idea of the government taking out extra debt to finance its stimulus measures – because after all, if you were personally experiencing a major financial crisis in your own household, wouldn’t the last thing you’d want to do be to take out a bunch of debt and use it to go on a massive spending spree? And this is a perfectly good point – if you’re talking about a private household. But crucially, the government isn’t the same as a private household; its financial health isn’t based on its ability to save up wealth for itself by taking more money out of the economy than it spends, because it’s the one issuing the money and putting it out into the broader economy in the first place. It wouldn’t make sense for it to try and hoard as much money as possible in order to run a surplus in the middle of a recession, because the only way for it to do so would be to take that money out of the broader economy, thereby reducing people’s spending power and causing the recession to deepen. As Rex Nutting explained during the post-2008 slump:

Balancing the budget immediately would be a catastrophe. Even large budget cuts would make the very weak recovery stall. It’s simple arithmetic: What the government spends becomes someone’s income, which they in turn can spend. Cutting government spending (or raising taxes) means cutting disposable incomes, and that means cutting economic growth. That’s why we don’t want any of this budget balancing to take effect for at least a couple of years. Once growth is stronger, the government can reduce spending and raise taxes without hurting the economy.

Of course, it’s worth stressing that if and when the government does decide to boost spending and/or cut taxes, it can’t just assume that any old spending boost or tax cut will be as effective as any other. Merely cutting taxes for rich people who already have a ton of excess savings, for instance, probably won’t do all that much for the broader economy, since in a zero-lower-bound situation the money will most likely just end up sitting idle in a bank vault somewhere without being spent or lent out. Far more effective would be to direct those tax breaks and spending increases toward poorer citizens, who will be more likely to go out and spend their money (since poorer people always have to spend a larger proportion of their income just to meet their basic needs), and who will therefore provide a bigger boost to the economy at large. In fact, for this same reason (and despite everything we’ve been saying about how tax increases are generally counterproductive for stimulus purposes), it can even be possible under the right circumstances to create some degree of fiscal stimulus by just taxing rich people’s idle excess savings and then redistributing that money to everyone else to spend into circulation. Either way though, whether the stimulus is coming from redistributive taxation or deficit spending (or both), the point here is just that when private firms and individuals are unable or unwilling to spend their money, the government can step in and spend it for them, by taxing or borrowing those unused dollars and putting them to use.

Now, at this point conservatives may raise another objection: If the government is borrowing and/or taxing away so much of people’s money like this, doesn’t that mean that it’s eating up all the private sector’s investment capital, and thereby “crowding out” all other investment opportunities? By reducing the amount of investable funds available in the private sector, won’t it drive up interest rates and make it more difficult for firms and individuals to borrow money? Again though, this is one of those things that, while it can indeed happen when the economy is booming, ceases to be an issue when the economy is deeply depressed. This was demonstrated decisively in the post-2008 recovery, as Krugman notes:

[After the 2008 crash,] opponents of stimulus argued vociferously that deficit spending would send interest rates skyrocketing, “crowding out” private spending. Proponents responded, however, that crowding out — a real issue when the economy is near full employment — wouldn’t happen in a deeply depressed economy, awash in excess capacity and excess savings. And stimulus supporters were right: far from soaring, interest rates fell to historic lows.

Krugman himself was one of the biggest pro-stimulus voices during this period when the economy was struggling to recover; and years later, his arguments still hold up. As he wrote at the time:

Let’s start with what may be the most crucial thing to understand: the economy is not like an individual family.

Families earn what they can, and spend as much as they think prudent; spending and earning opportunities are two different things. In the economy as a whole, however, income and spending are interdependent: my spending is your income, and your spending is my income. If both of us slash spending at the same time, both of our incomes will fall too.

And that’s what happened after the financial crisis of 2008. Many people suddenly cut spending, either because they chose to or because their creditors forced them to; meanwhile, not many people were able or willing to spend more. The result was a plunge in incomes that also caused a plunge in employment, creating the depression that persists to this day.

Why did spending plunge? Mainly because of a burst housing bubble and an overhang of private-sector debt — but if you ask me, people talk too much about what went wrong during the boom years and not enough about what we should be doing now. For no matter how lurid the excesses of the past, there’s no good reason that we should pay for them with year after year of mass unemployment.

So what could we do to reduce unemployment? The answer is, this is a time for above-normal government spending, to sustain the economy until the private sector is willing to spend again. The crucial point is that under current conditions, the government is not, repeat not, in competition with the private sector. Government spending doesn’t divert resources away from private uses; it puts unemployed resources to work. Government borrowing doesn’t crowd out private investment; it mobilizes funds that would otherwise go unused.

Now, just to be clear, this is not a case for more government spending and larger budget deficits under all circumstances — and the claim that people like me always want bigger deficits is just false. For the economy isn’t always like this — in fact, situations like the one we’re in are fairly rare. By all means let’s try to reduce deficits and bring down government indebtedness once normal conditions return and the economy is no longer depressed. But right now we’re still dealing with the aftermath of a once-in-three-generations financial crisis. This is no time for austerity.

He concluded with this point:

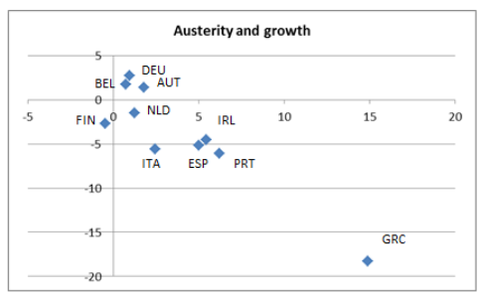

This view of our problems [as explained above] has made correct predictions over the past four years, while alternative views have gotten it all wrong. Budget deficits haven’t led to soaring interest rates (and the Fed’s “money-printing” hasn’t led to inflation); austerity policies have greatly deepened economic slumps almost everywhere they have been tried.

And it’s true; in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis (which was a truly global crisis, not just an American one), the countries that relied most heavily on austerity policies to save them from their economic troubles – like Portugal, Spain, and Ireland – were the ones whose slumps subsequently worsened most dramatically (not even mentioning Greece, which was a whole separate basket case of its own).

It might seem hard to believe that a national strategy of financial belt-tightening, which is so undeniably prudent and responsible in so many other circumstances, could be so disastrously wrong when economic conditions are at their most dire. But Michael J. Wilson sums up why this is in fact the case, and captures the core of the matter with a great analogy:

Deficits occur when the economy drags: think of the Reagan Recession of the early 1980s and [the post-2008] Great Recession. That’s because federal revenue falls at the same time that [the need for] vital safety net programs such as unemployment compensation and food stamps increases. Repairing our budget really starts by repairing our economy. And that repair begins with increased demand. But consumers are unable to spend if they are burdened by debt and millions are out of work — or worried they soon will be. Companies are unwilling to hire or invest in this uncertain economic environment. There’s only one entity left to prime the pump: the federal government. The seeming paradox of the government needing to spend more to balance the budget is not really all that strange. Short-term and long-term prescriptions are often at odds. Think about it: Exercise is generally a good idea, but not when you’re flat on your back with a broken leg. Once the economy is back on its feet again, spending can be addressed as part of the effort to control deficits — deficits which, not so incidentally, will be lower because of the tax revenue being generated by a robust economy.

His last point there is also worth noting; if your true long-term goal is to keep the national debt from growing too large, then even on that basis alone it’s no reason to avoid heavy government spending in a recession, but on the contrary is all the more reason to want the government to spend big in the short term so as to restore the economy to full health as quickly as possible and minimize the fiscal damage over the long term. True, it’ll cost more up front, but ultimately the results will pay for themselves and then some – whereas by contrast, an austerity-based strategy will only prolong and worsen the economic losses, as Krugman points out:

Cutting spending in a deeply depressed economy is largely self-defeating even in purely fiscal terms: any savings achieved at the front end are partly offset by lower revenue, as the economy shrinks.

As he sums it all up, then, the prescription is simple:

Slumps [can] be fought with appropriate government policies: low interest rates for relatively mild recessions, deficit spending for deeper downturns. And given these policies, much of the rest of the economy [can] be left up to markets.

Of course, I say “simple” – and even Keynes himself described this as a “moderately conservative” approach to macroeconomic issues (in contrast to, say, the Marxist model that economic crises must bring about the destruction of the entire system) – but in the eyes of many anti-statists, any amount of government intervention is too much, so not even small interventions can be accepted, much less large-scale ones that affect the entire economy. To them, government intervention does nothing but suck valuable money out of the economy and throw it away on useless endeavors – as if it were basically removing that wealth from the economy altogether. But this critique – or at least the crudest version of it – reflects a major misunderstanding of how public spending works. When the government taxes or borrows money from the private sector, it isn’t just piling all the money in a corner and burning it; it’s turning right back around and putting the money back into the pockets of the people whom it hires to perform government services. It’s no different from if those people were still working in the private sector; it’s just that instead of having their wages paid directly to them by other people in the private sector in exchange for their services, the money is first collected by the government, and then paid to them in exchange for their services. The end result is largely the same; it’s just that the money passes through an intermediary first. What’s more, the argument that hiring people in this way takes valuable money and labor away from being invested in productive and efficient private-sector uses in favor of unproductive and inefficient public ones is likewise flawed – because when the economy is depressed, those resources aren’t being used anyway; so it’s not a matter of government investment versus private investment – it’s a matter of government investment versus no investment at all.

Still though, what about the broader conservative critique of government spending in general, outside just the narrow context of economic depressions? Isn’t there some truth to the old stereotype that government spending tends to be horrendously wasteful compared to the private sector? Well, obviously the answer depends on the government, and on what kind of spending it’s choosing to pursue. Certainly it’s possible to have a government overextend itself and pursue projects that really are wasteful and inefficient – my whole last post was all about how governments can produce all kinds of abysmal results by trying to do things that are better left to the private sector. But on the other side of the coin, this whole post has just been one long extended discussion of all the areas where the government spending can actually be more effective and efficient than the private sector, and in many cases can accomplish things that the private sector simply can’t (or won’t) accomplish at all. So clearly it’s a matter of context. To be sure, the market mechanism is tremendously effective at providing most of our everyday goods and services at the lowest possible cost. But government still has a valuable role to play in filling the gaps that the market isn’t quite capable of perfectly covering. And in fact, one of the biggest points in its favor is that when it does need to spend money, it can often itself do so in a way that takes advantage of the market mechanism, as Wheelan points out:

Even [in situations where] government has an important role to play in the economy, such as building roads and bridges, it does not follow that government must actually do the work. Government employees do not have to be the ones pouring cement. Rather, government can plan and finance a new highway and then solicit bids from private contractors to do the work. If the bidding process is honest and competitive (big “ifs” in many cases), then the project will go to the firm that can do the best work at the lowest cost. In short, a public good is delivered in a way that harnesses all the benefits of the market.

In areas where the government is able to do this, the criticism that its spending is less cost-efficient than the private sector’s falls flat, because the government funds in such cases actually are being spent on private-sector work – and not only that, the spending is being done in the most competitive and price-efficient manner possible. Wheelan continues:

This distinction is sometimes lost on American taxpayers, a point that Barack Obama made during one of his town hall meetings on health care reform. He said, “I got a letter the other day from a woman. She said, ‘I don’t want government-run healthcare. I don’t want socialized medicine. And don’t touch my Medicare.’” The irony, of course, is that Medicare is government-run health care; the program allows Americans over age 65 to seek care from their private doctors, who are then reimbursed by the federal government.

This example is particularly noteworthy because the government not only runs Medicare efficiently, but in many ways runs it more efficiently than private health insurance. Private insurers’ administrative costs (that is, their “bureaucracy” and “red tape”) amount to around 15% of their overall funds – as opposed to Medicare’s 2% – and for that reason (among others, such as marketing expenses and payments to shareholders), private insurance costs billions of dollars more than Medicare to pay for the same treatments (see here and here). In other words, the government-sponsored option is by far the less bureaucratic and wasteful of the two.

Again, that’s not always the case; Wheelan is right to say that it’s often a big “if” whether having the government outsource its functions to private-sector contractors will really be the most cost-effective option for any given project. As this post illustrates, it will often be cheaper to simply have the government do the job itself, with its own employees that it hires directly. But in either case, the idea that government-sponsored undertakings are always significantly more wasteful than private ones is, to put it mildly, often considerably overstated by conservatives. I already quoted part of this excerpt from Alexander earlier, but I’ll just quote the fuller version here now:

[Q]: Large government projects are always late and over-budget.

The only study on the subject I could find, “What Causes Cost Overrun in Transport Infrastructure Projects?” (download study as .pdf) by Flyvbjerg, Holm, and Buhl, finds no difference in cost overruns between comparable government and private projects, and in fact find one of their two classes of government project (those not associated with a state-owned enterprise) to have a trend toward being more efficient than comparable private projects. They conclude that “…one conclusion is clear…the conventional wisdom, which holds that public ownership is problematic whereas private ownership is a main source of efficiency in curbing cost escalation, is dubious.”

Further, when government cost overruns occur, they are not usually because of corrupt bureaucrats wasting the public’s money. Rather, they’re because politicians don’t believe voters will approve their projects unless they spin them as being much cheaper and faster than the likely reality, leading a predictable and sometimes commendable execution to be condemned as “late and over budget” (download study as .pdf) While it is admittedly a problem that government provides an environment in which politicians have to lie to voters to get a project built, the facts provide little justification for a narrative in which government is incompetent at construction projects.

[Q]: State-run companies are always uncreative, unprofitable, and unpleasant to use.

Some of the greatest and most successful companies in the world are or have been state-run. Japan National Railways, which created the legendarily efficient bullet trains, and the BBC, which provides the most respected news coverage in the world as well as a host of popular shows like Doctor Who, both began as state-run corporations (JNR was later privatized).

In cases where state-run corporations are unprofitable, this is often not due to some negative effect of being state-run, but because the corporation was put under state control precisely because it was something so unprofitable no private company would touch it, but still important enough that it had to be done. For example, the US Post Office has a legal mandate to ship affordable mail in a timely fashion to every single god-forsaken town in the United States; obviously it will be out-competed by a private company that can focus on the easiest and most profitable routes, but this does not speak against it. Amtrak exists despite passenger rail travel in the United States being fundamentally unprofitable, but within its limitations it has done a relatively good job: on-time rates better than that of commercial airlines, 80% customer satisfaction rate, and double-digit year-on-year passenger growth every year for the past decade.

To reiterate, none of this is to suggest that it makes no difference whether big important projects are handled by the public sector or the private sector, and that therefore we might as well nationalize everything. Most of the time, the market mechanism really will be the cheapest and most effective way of getting things done in the economy, and we forget that at our own peril. The point here is just that it isn’t the only way of getting things done. Trying to run an entire economy solely through the market mechanism, without any kind of government intervention at all, would be dramatically less efficient and effective than running a mixed economy that takes full advantages of both the public and private sectors’ strengths. This is especially apparent in times of economic crisis, like during recessions or inflationary spirals – but it’s no less true even during normal times. Good government is what allows the market to reach its full potential, and to operate as smoothly and productively as possible.