I – II – III – IV – V

[Single-page view]

But again, I’m getting ahead of myself; let’s back up one more time. The way Kurzweil explains it, the upcoming explosion of technological progress will actually feature three overlapping revolutions – three areas where its impact will be greatest – in biotechnology, nanotechnology, and AI. We can already see progress in these areas beginning to ramp up in some clear ways: With biotechnology, for instance, we’ve long had the ability to augment our bodies with machines to improve their functioning – e.g. with pacemakers and hearing aids and so on – but more recently we’ve expanded this to include implants in the brain as well, which can stop the effects of conditions like epilepsy, OCD, and Parkinson’s Disease, and are even being developed to treat depression and Alzheimer’s Disease. There have also been major recent breakthroughs in developing technologies to grow replacement organs from scratch in the lab, so that patients with failing organs can get new ones fabricated on demand without the need for organ donors. And even more dramatic leaps are being made in the area of genetic engineering, which can and will give us the power to reprogram our own biology at the most fundamental level; the first babies have already been born who’ve had their genomes edited to make them immune to certain diseases, and in time this will only become more commonplace. It won’t be long before everyone is customizing their babies’ genomes to not only give them immunity to diseases, but also things like enhanced metabolism, perfect eyesight, peak physique, heightened intelligence, and more. Kurzgesagt has a great video on the subject:

And this is only the tip of the iceberg. Just in the last few years, there have been decades’ worth of breakthroughs in biotechnology, as Sveta McShane points out:

Major innovations in biotech over the last decade include:

And in fact, just since that article was posted in 2016, we’ve had multiple breakthroughs which on their own would be considered once-in-a-lifetime advances. We’ve developed a brain implant that can help treat blindness. We’ve grown a mouse embryo from nothing but stem cells, without the use of sperm or eggs or a womb. We’ve discovered an effective cure for obesity – one which, unbelievably, also seems to work as a treatment for a whole array of other things, from diabetes to alcoholism to drug addiction to heart disease to kidney disease to stroke to Parkinson’s to Alzheimer’s to COVID-19. And speaking of COVID, our efforts against the COVID pandemic allowed us to unlock a whole new category of vaccines, mRNA vaccines, which could potentially lead to cures not only for COVID, but for a whole slew of other diseases which currently kill millions, including malaria, HIV, and even various types of cancer, as Noah Smith notes:

Vaccine technology just took a huge leap forward. Propelled by the crisis of COVID, mRNA vaccines went from a speculative tool to a proven one. This will probably accelerate the development of all kinds of new vaccines, potentially including vaccines for cancer. It’s worth reading that phrase again and thinking about it for a second: VACCINES FOR CANCER.

And again, all of this is just what’s happening right now; we haven’t even gotten into the breakthroughs that we’re on track to make in the near future. The way things are going (and assuming we don’t screw things up in the meantime somehow), it’ll only be a matter of time before we’re able to introduce respirocytes into our bloodstreams – tiny robotic blood cells that will enable us to run for 15 minutes at a dead sprint without getting winded, or sit at the bottom of a swimming pool for hours without taking a breath. We’ll have technologies that will allow us to recover from practically any injury (even the most debilitating ones), like salamanders re-growing lost limbs. We’ll even have the ability to counteract the cellular degeneration that causes our bodies to break down as we get older; that is, we’ll have the ability to reverse the aging process itself. I’ve posted this TED talk from Aubrey de Grey here before, but I think it’s worth posting again just because what he’s talking about here is so remarkable:

It’s hard to overstate the significance of all this. Being able to extend human lifespans indefinitely – to conquer death itself (or at least “natural death”) – would be by far the most momentous development in human history. (And we’ll come back to this point in a moment.) But even aside from matters of lifespan and mortality, the implications of all these technologies just in terms of everyday quality of life would be indescribable. If you’re someone who’s currently feeling despondent, for instance, because you feel like you missed your window to have kids and now you’re too old, well, you might soon be able to restore your body back to its youthful peak condition and have another chance (either via old-fashioned pregnancy or through the use of an artificial womb). Quadriplegic? Hang in there; you just might be able to get the full use of your body back in time. Suffering from any kind of chronic health condition at all? As wild as it sounds, it’s no exaggeration to say that given the continuing acceleration of progress in medicine and biotechnology, there might not be any kind of malady whatsoever that doesn’t have a legitimately good chance of becoming curable within our lifetimes.

But as big as the impact of these technologies would be on our ability to remedy our maladies and keep ourselves in perfect condition, the place where the implications would be biggest of all would be in enhancing not just our physical abilities, but our brainpower. I already briefly mentioned gene editing as one potential way of enhancing human intelligence, but we’re also likely to see increasingly rapid advancement of technologies designed to boost intelligence in even more direct ways, e.g. via chemical and/or pharmaceutical means (AKA nootropics). Even more potent still is the emerging technology of brain-machine interfacing – hooking up a person’s brain to a computer and thereby augmenting their own natural thinking abilities with all the additional capabilities of the computer. This technology has already come into use as a tool for enabling people with severe disabilities to do things they wouldn’t normally be able to do; for instance, here’s a sample of “handwriting” from a man who, despite being paralyzed from the neck down, was able to use a brain-computer interface to make the letters appear onscreen simply by thinking about writing them:

And this technology is only going to become more sophisticated in the next few years. As we become better and better at designing machines that can directly integrate with our brains, it will eventually progress to a point where we’re able to significantly enhance the speed, memory, and storage capacity of our brains using computer peripherals. In other words, we’ll gain the ability to upgrade our own brainpower. And when that happens, all bets are off when it comes to making even more dramatic subsequent leaps in advancement – because as Eliezer Yudkowsky points out, our level of intelligence is the pivotal factor determining our rate of scientific and technological progress:

The great breakthroughs of physics and engineering did not occur because a group of people plodded and plodded and plodded for generations until they found an explanation so complex, a string of ideas so long, that only time could invent it. Relativity and quantum physics and buckyballs and object-oriented programming all happened because someone put together a short, simple, elegant semantic structure in a way that nobody had ever thought of before. Being a little bit smarter is where revolutions come from. Not time. Not hard work. Although hard work and time were usually necessary, others had worked far harder and longer without result. The essence of revolution is raw smartness.

“Think about a chimpanzee trying to understand integral calculus,” he adds. No matter how persistent or well-resourced the chimp is, there’s simply no way it will ever be able to succeed. Give the chimp a bit of extra brainpower, though – enough to put it at the level of a fairly smart human – and all of a sudden the impossible task becomes perfectly feasible. And the same is true of us humans and our current levels of intelligence; boost it just a little, and we suddenly become capable of making breakthroughs that might previously have seemed impossible:

There are no hard problems, only problems that are hard to a certain level of intelligence. Move the smallest bit upwards, and some problems will suddenly move from “impossible” to “obvious”. Move a substantial degree upwards, and all of them will become obvious.

The development of technology for enhancing intelligence is the master key to our entire future – because as soon as we do develop such a technology, it will allow us to even more quickly develop more technologies for enhancing our intelligence further still, which will allow us to develop even more technologies for enhancing our intelligence further still, and so on in an exponentially accelerating positive feedback loop until we’ve reached seemingly impossible heights of advancement. The breakthroughs will just keep coming faster and faster until practically overnight our entire world is transformed. That’s what could potentially be in our very near future – or at least, that’s what it could look like if we go the biotechnology route. As it happens, though, biotechnology isn’t actually the only means by which we might unlock the capacity for self-improving intelligence. Another is the second of Kurzweil’s three overlapping revolutions – AI.

The term “AI” can refer to a few different things. At the most rudimentary level, it can just refer to things like GPS devices and chess-playing computers and digital assistants like Siri and Alexa, which are already so widespread that you’ve probably interacted with several of them yourself recently. These are what are called “narrow AIs,” because while they’re great for accomplishing certain very specific tasks (and can even outperform humans within those specialized sub-domains), they aren’t much use outside those narrow contexts, and so can’t rightly be considered “just as intelligent as a human” in the most general sense. When we’re talking about truly revolutionary AI, though, we aren’t just talking about these kinds of limited-use tools; what we’re talking about instead is AI that actually would be considered as intelligent as a human in the general sense – so-called “artificial general intelligence,” or AGI. As Urban describes it, this is AI “that is as smart as a human across the board—a machine that can perform any intellectual task that a human being can.”

So how could we create such an AI? Well, the first thing we’d need to do would be to simply make sure that we actually have hardware powerful enough to operate at a comparable level to the human brain. The brain is capable of running at a rate that, in computing terms, would be the equivalent of up to one quintillion operations per second – a level of performance that, for most of computing history, has been far out of reach. But as computing power has continued to advance at an accelerating rate, we’ve finally gotten to the point where we actually have just now crossed that critical threshold. We’re now building supercomputers that really can match the performance of the human brain. All that’s left for us to do at this point, then, is to figure out the software side of the equation – i.e. how to encode something as intelligent as a human brain in a digital format. And obviously, that’s not something that anyone would be able to do just by programming in every line of code from scratch; nobody understands the brain that well (at least not currently). So what we’ve done instead is come up with some shortcuts – strategies that would allow us to create an advanced digital intelligence even without fully understanding it first.

The most straightforward such strategy would be to simply plagiarize the brain wholesale – to develop brain-scanning technology of such high resolution that it would be able to map out an entire brain with perfect accuracy, down to the level of individual neurons and synapses, and then recreate that brain virtually. In this scenario, the newly-created digital brain would be functionally identical to the original human brain – but because it was on a computer, it would be able to process information millions of times faster, would have vastly more capacity for expanded memory, and so on. (A normal human brain, on its own, actually processes information quite slowly compared to a computer; it’s only able to perform so many operations per second because of its massively parallel structure, which allows it to process many different streams of information at once. But in a digital format, it would be able to process those same information streams at near-lightspeed.) This would make it exponentially more powerful and capable – and that’s not even mentioning possibilities like being able to instantaneously upgrade the digital brain with new knowledge, being able to network it with other digital intelligences, and so on. The potential here would be practically limitless.

Unfortunately, despite rapidly coming ever closer to achieving the kind of perfect brain-scanning resolution necessary to map out the entire human brain in this way, we haven’t quite gotten there just yet; the technology is still years away from being perfected at this point. (As of just recently, it has gotten good enough to completely map out the brain of a fruit fly, which is an incredible accomplishment in its own right, but that’s still quite a ways from being able to do the same for a human brain.) In the meantime, though, other methods for creating digital intelligence, such as machine learning, have surged to the fore, and are making huge leaps at an incredible pace. Developers have discovered that the old-fashioned way of building an AI – explicitly programming in every line of code by hand – isn’t actually necessary, and that it’s possible instead to build AI that can essentially “teach” itself, simply by giving it massive quantities of sample data to draw from and then instructing it to identify whatever patterns it can find in that data, extrapolate from those patterns to generate its own output, and make subsequent adjustments based on the quality of that output. And the results have frankly been astonishing. Just as recently as 2016, if you’d taken the most cutting-edge AI and instructed it to write something based on the phrase “It was the best of times,” its output would have been little better than the text autocomplete feature on your smartphone; as Asterisk illustrates:

It was the best of times but this is how things continue and it would be a tragedy if the airlines canceled

It was the best of times and it ‘s cheaper ( Bloodaxe ) . </S>

It was the best of times… there are no better days but they come with higher fare , so a price

Two years later, in 2018, here’s how it was responding:

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times. i wasn’t even sure how long i ‘d be on the road. when i came back to l.a., ┕i was sure that i would come home, and that was when i wanted to go home. ut. 2

Then a year after that, in 2019:

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times. I was going to college in San Francisco, and I’d be walking from one class to another, and I’d feel so much tension between this world of my own and this one, between the city and the country. My parents had moved their family so much that that they were making it difficult for me me me.

And now here’s 2022:

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times. It was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness. It was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity. It was the season of light, it was the season of darkness. It was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair. We had everything before us, we had nothing before us. We were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way.

The opening line of Charles Dickens’ “A Tale of Two Cities” paints a powerful portrait of the teetering social and political climate of late 18th century France. The extremes of best and worst, wisdom and foolishness, belief and incredulity, light and darkness, hope and despair, capture the spirit of an era pre-Revolutionary France – an era of great uncertainty, anticipation, and excitement. As the story progresses, the plight of the French people is made all too clear as they grapple with grave societal injustices, revolutionary fervor, and the uncertainty of what their newfound freedom will bring.

If you haven’t been paying much attention to how AI has been advancing these past few years – or even if you have been, for that matter – this is absolutely stunning. Nobody programmed the AI to give this response. Nobody explicitly taught it how to string together a grammatically correct sentence, or how to contextualize the themes of a story, or what a story even is (much less what A Tale of Two Cities is specifically). Its creators simply gave it a bunch of sample text from the internet (along with some corrective feedback as it interpreted that training data), and it figured out the rest on its own. It independently worked out which concepts were most relevant to the prompt, how to tie those concepts together coherently, and how to present them in a clear way – something that would be difficult even for many humans to do.

And its abilities aren’t just limited to summarizing publicly-available information, either. The newest version of this AI can contextualize and make inferences from incomplete information…

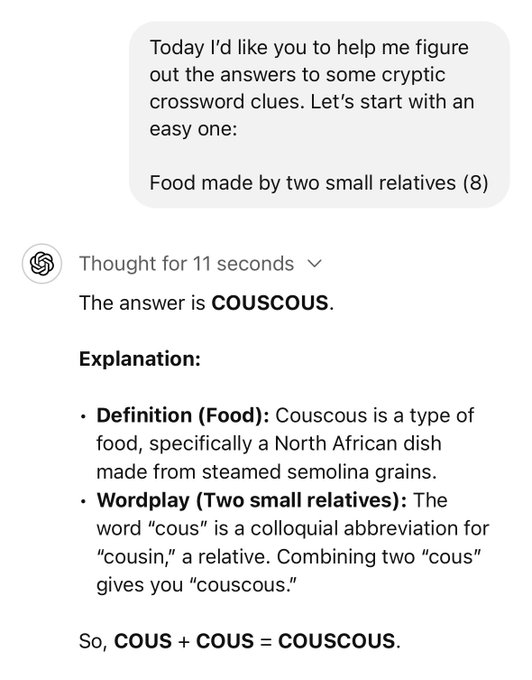

…solve puzzles that require a nuanced grasp of linguistic ambiguity and wordplay…

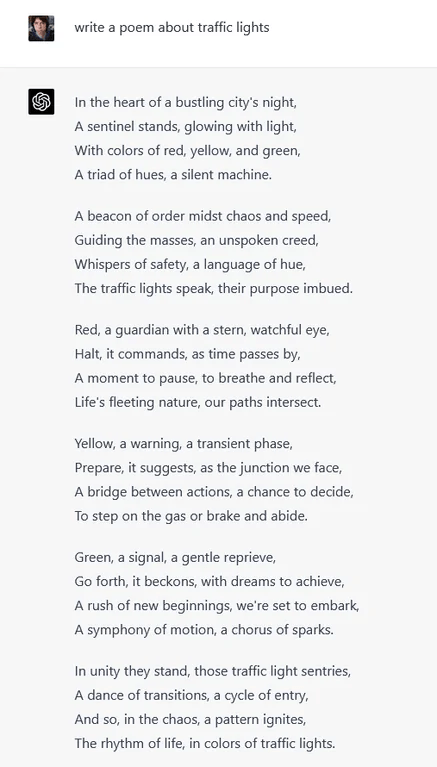

…write poems (with consistent internal meters and rhyme schemes)…

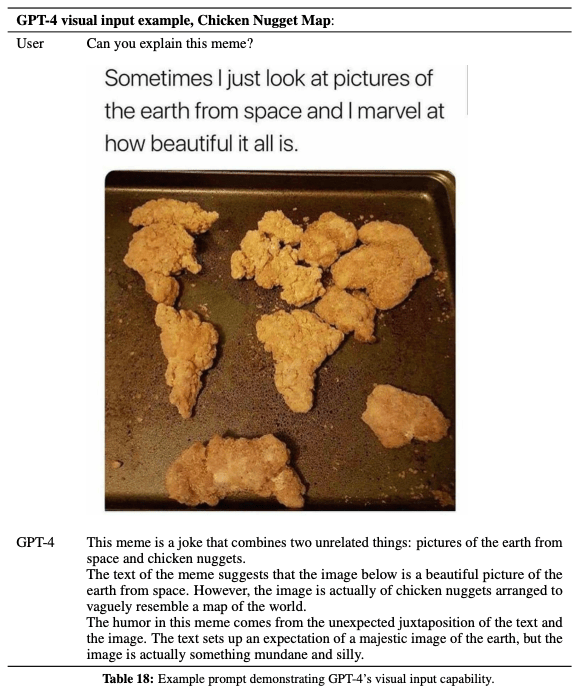

…and even “understand” humor – including visual jokes that require the ability to parse not only text but also images:

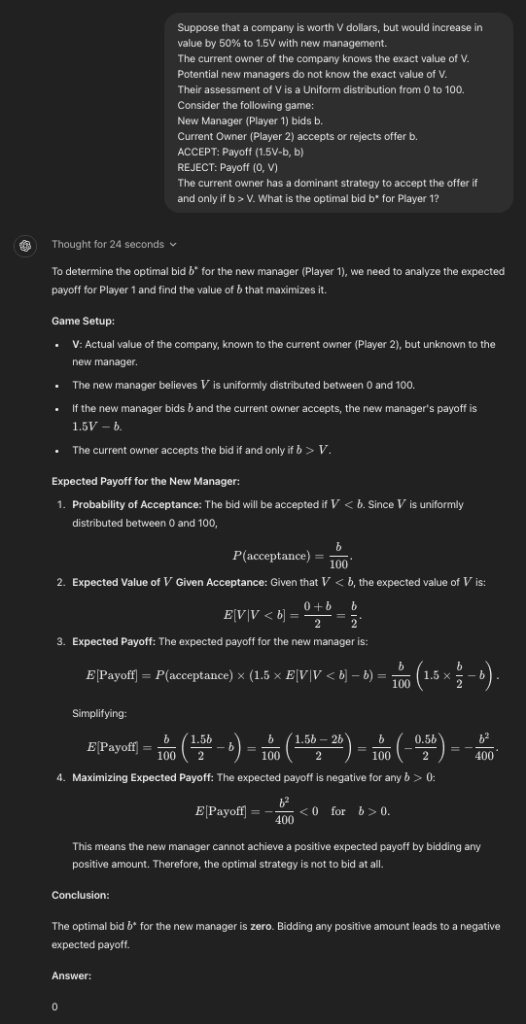

What’s more, AI’s capabilities now extend into “harder” fields like science, math, and economics. Posed with difficult or unintuitive problems in these areas, modern AIs can solve them effortlessly:

And they’re even smart enough now to ace advanced exams in all kinds of fields, scoring in the 90th percentile or better on the SAT, the bar exam, and a whole host of AP exams ranging from history to biology to economics to statistics and more. The latest AI models have even gotten to the point where they’re scoring at these levels in tests like the International Mathematical Olympiad – the hardest math test in the world for students.

Nor is this exponential progress merely limited to text-based output. Modern AIs are now capable of producing photorealistic images and video clips, breathtaking works of art, near-perfect audio imitations of specific human voices, and more – and their capabilities in these areas are improving at a pace that’s simply staggering. Case in point – here’s what pure AI-generated video looked like in 2023:

And now here’s what it looks like in 2024, just one(!) year later:

And similarly, here are a few short demonstrations showing what it’s like to have a chat with a voice-enabled AI today (in contrast with the rudimentary voice assistants of just a year or two ago):

All these capabilities would have been unimaginable even as recently as a decade ago. They would have sounded like pure sci-fi – the kind of stuff that was surely decades if not centuries away. But now, practically overnight, they’ve become real.

To say, then, that modern AI development is a prime example of exponentially accelerating technological progress would be an understatement. This is one of the most dramatic examples (if not the most dramatic example) of accelerating progress in the history of technology. Like the proverbial patch of lily pads that barely seemed to be growing at all until the final week of the year when its growth suddenly exploded, the field of AI spent its first few decades puttering along at a leisurely pace, never really seeming to make all that much progress – but now, all of a sudden, it has hit the knee of the exponential curve, and its progress is skyrocketing.

It’s not hard to see where all this is heading. If AI progress continues at even a fraction of its current rate, it’ll hardly be any time at all before the list of areas where AI has surpassed human capabilities has expanded so much that it has subsumed practically everything – including, crucially, AI research and development itself. The closer AIs get to reaching human-equivalent levels in areas like computer programming (and as you can see from the clip above, in which an AI instantly codes an entire app all by itself, they’re already nearly there), the closer they’ll be to being able to improve their own code. And when that happens, we really will see a multiplicative effect on their rate of advancement unlike anything we’ve ever seen before. In the blink of an eye, we’ll catapult from practically-human-level AIs to vastly-more-intelligent-than-human AIs; and at that point, there’ll be no limit to what they’re capable of. As Kelsey Piper explains:

[A well-known idea in the field of AI is] the idea of recursive self-improvement — an AI improving at the art of making smarter AI systems, which would then make even smarter AI systems, such that we’d rapidly go from human-level to vastly superhuman-level AI.

In a 1965 paper, pioneering computer scientist I. J. Good posed the first scenario of runaway machine intelligence:

Let an ultraintelligent machine be defined as a machine that can far surpass all the intellectual activities of any man however clever. Since the design of machines is one of these intellectual activities, an ultraintelligent machine could design even better machines; there would then unquestionably be an “intelligence explosion,” and the intelligence of man would be left far behind. Thus the first ultraintelligent machine is the last invention that man need ever make.

Good used the term “intelligence explosion,” but many of his intellectual successors picked the term “singularity,” sometimes attributed to John von Neumann and made popular by mathematician, computer science professor, and science fiction author Vernor Vinge.

And the Singularity Institute elaborates:

The Singularity is the technological creation of smarter-than-human intelligence. There are several technologies that are often mentioned as heading in this direction. The most commonly mentioned is probably Artificial Intelligence, but there are others: direct brain-computer interfaces, biological augmentation of the brain, genetic engineering, ultra-high-resolution scans of the brain followed by computer emulation. Some of these technologies seem likely to arrive much earlier than the others, but there are nonetheless several independent technologies all heading in the direction of the Singularity – several different technologies which, if they reached a threshold level of sophistication, would enable the creation of smarter-than-human intelligence.

A future that contains smarter-than-human minds is genuinely different in a way that goes beyond the usual visions of a future filled with bigger and better gadgets. Vernor Vinge originally coined the term “Singularity” in observing that, just as our model of physics breaks down when it tries to model the singularity at the center of a black hole, our model of the world breaks down when it tries to model a future that contains entities smarter than human.

Human intelligence is the foundation of human technology; all technology is ultimately the product of intelligence. If technology can turn around and enhance intelligence, this closes the loop, creating a positive feedback effect. Smarter minds will be more effective at building still smarter minds. This loop appears most clearly in the example of an Artificial Intelligence improving its own source code, but it would also arise, albeit initially on a slower timescale, from humans with direct brain-computer interfaces creating the next generation of brain-computer interfaces, or biologically augmented humans working on an Artificial Intelligence project.

At the time this was written (over a decade ago), it was still something of a tossup whether AI would be the first technology that would allow for recursive self-improvement, or whether other methods like genetic engineering or brain augmentation would get there first. But today, AI has become the clear frontrunner. And in fact, in some small ways, the process of AI improving itself is already underway. Jack Soslow gives a few examples:

AI has begun improving itself.

1. AlphaTensor — Optimizes matrix multiplication https://tinyurl.com/yeyrakfp

2. PrefixRL — Optimizes circuit placement on chips https://arxiv.org/abs/2205.07000

3. LLMs can self improve — LLMs fine-tune on their own generations https://tinyurl.com/j7j298m7

Right now these capabilities might seem relatively minor. But the closer AIs get to human levels of intelligence, the more powerful they’ll become – and the better they’ll get at improving themselves. And what this means, in practical terms, is that as soon as AIs actually do reach human-equivalent levels of intelligence, they’ll already be superhuman – because after all, even at mere “human levels of intelligence,” they’ll already have so many additional advantages over humans that they’ll be orders of magnitude more capable before they’re even out of the gate. As Urban explains:

At some point, we’ll have achieved AGI—computers with human-level general intelligence. Just a bunch of people and computers living together in equality.

Oh actually not at all.

The thing is, AGI with an identical level of intelligence and computational capacity as a human would still have significant advantages over humans. Like:

Hardware:

- Speed. The brain’s neurons max out at around 200 Hz, while today’s microprocessors (which are much slower than they will be when we reach AGI) run at 2 GHz, or 10 million times faster than our neurons. And the brain’s internal communications, which can move at about 120 m/s, are horribly outmatched by a computer’s ability to communicate optically at the speed of light.

- Size and storage. The brain is locked into its size by the shape of our skulls, and it couldn’t get much bigger anyway, or the 120 m/s internal communications would take too long to get from one brain structure to another. Computers can expand to any physical size, allowing far more hardware to be put to work, a much larger working memory (RAM), and a longterm memory (hard drive storage) that has both far greater capacity and precision than our own.

- Reliability and durability. It’s not only the memories of a computer that would be more precise. Computer transistors are more accurate than biological neurons, and they’re less likely to deteriorate (and can be repaired or replaced if they do). Human brains also get fatigued easily, while computers can run nonstop, at peak performance, 24/7.

Software:

- Editability, upgradability, and a wider breadth of possibility. Unlike the human brain, computer software can receive updates and fixes and can be easily experimented on. The upgrades could also span to areas where human brains are weak. Human vision software is superbly advanced, while its complex engineering capability is pretty low-grade. Computers could match the human on vision software but could also become equally optimized in engineering and any other area.

- Collective capability. Humans crush all other species at building a vast collective intelligence. Beginning with the development of language and the forming of large, dense communities, advancing through the inventions of writing and printing, and now intensified through tools like the internet, humanity’s collective intelligence is one of the major reasons we’ve been able to get so far ahead of all other species. And computers will be way better at it than we are. A worldwide network of AI running a particular program could regularly sync with itself so that anything any one computer learned would be instantly uploaded to all other computers. The group could also take on one goal as a unit, because there wouldn’t necessarily be dissenting opinions and motivations and self-interest, like we have within the human population.

AI, which will likely get to AGI by being programmed to self-improve, wouldn’t see “human-level intelligence” as some important milestone—it’s only a relevant marker from our point of view—and wouldn’t have any reason to “stop” at our level. And given the advantages over us that even human intelligence-equivalent AGI would have, it’s pretty obvious that it would only hit human intelligence for a brief instant before racing onwards to the realm of superior-to-human intelligence.

As Scott Alexander sums up:

By hooking a human-level AI to a calculator app, we can get it to the level of a human with lightning-fast calculation abilities. By hooking it up to Wikipedia, we can give it all human knowledge. By hooking it up to a couple extra gigabytes of storage, we can give it photographic memory. By giving it a few more processors, we can make it run a hundred times faster, such that a problem that takes a normal human a whole day to solve only takes the human-level AI fifteen minutes.

So we’ve already gone from “mere human intelligence” to “human with all knowledge, photographic memory, lightning calculations, and solves problems a hundred times faster than anyone else.” This suggests that “merely human level intelligence” isn’t mere.

The next [step] is “recursive self-improvement”. Maybe this human-level AI armed with photographic memory and a hundred-time-speedup takes up computer science. Maybe, with its ability to import entire textbooks in seconds, it becomes very good at computer science. This would allow it to fix its own algorithms to make itself even more intelligent, which would allow it to see new ways to make itself even more intelligent, and so on. The end result is that it either reaches some natural plateau or becomes superintelligent in the blink of an eye.

And that choice of words there, “in the blink of an eye,” is hardly an exaggeration. Urban drives the point home:

There is some debate about how soon AI will reach human-level general intelligence. The median year on a survey of hundreds of scientists about when they believed we’d be more likely than not to have reached AGI was 2040—that’s only [15] years from now, which doesn’t sound that huge until you consider that many of the thinkers in this field think it’s likely that the progression from AGI to ASI [artificial superintelligence] happens very quickly. Like—this could happen:

It takes decades for the first AI system to reach low-level general intelligence, but it finally happens. A computer is able to understand the world around it as well as a human four-year-old. Suddenly, within an hour of hitting that milestone, the system pumps out the grand theory of physics that unifies general relativity and quantum mechanics, something no human has been able to definitively do. 90 minutes after that, the AI has become an ASI, 170,000 times more intelligent than a human.

Superintelligence of that magnitude is not something we can remotely grasp, any more than a bumblebee can wrap its head around Keynesian Economics. In our world, smart means a 130 IQ and stupid means an 85 IQ—we don’t have a word for an IQ of 12,952.

Yudkowsky concludes:

The rise of human intelligence in its modern form reshaped the Earth. Most of the objects you see around you, like these chairs, are byproducts of human intelligence. There’s a popular concept of “intelligence” as book smarts, like calculus or chess, as opposed to say social skills. So people say that “it takes more than intelligence to succeed in human society”. But social skills reside in the brain, not the kidneys. When you think of intelligence, don’t think of a college professor, think of human beings; as opposed to chimpanzees. If you don’t have human intelligence, you’re not even in the game.

Sometime in the next few decades, we’ll start developing technologies that improve on human intelligence. We’ll hack the brain, or interface the brain to computers, or finally crack the problem of Artificial Intelligence. Now, this is not just a pleasant futuristic speculation like soldiers with super-strong bionic arms. Humanity did not rise to prominence on Earth by lifting heavier weights than other species.

Intelligence is the source of technology. If we can use technology to improve intelligence, that closes the loop and potentially creates a positive feedback cycle. Let’s say we invent brain-computer interfaces that substantially improve human intelligence. What might these augmented humans do with their improved intelligence? Well, among other things, they’ll probably design the next generation of brain-computer interfaces. And then, being even smarter, the next generation can do an even better job of designing the third generation. This hypothetical positive feedback cycle was pointed out in the 1960s by I. J. Good, a famous statistician, who called it the “intelligence explosion”. The purest case of an intelligence explosion would be an Artificial Intelligence rewriting its own source code.

The key idea is that if you can improve intelligence even a little, the process accelerates. It’s a tipping point. Like trying to balance a pen on one end – as soon as it tilts even a little, it quickly falls the rest of the way.

The potential impact on our world is enormous. Intelligence is the source of all our technology from agriculture to nuclear weapons. All of that was produced as a side effect of the last great jump in intelligence, the one that took place tens of thousands of years ago with the rise of humanity.

So let’s say you have an Artificial Intelligence that thinks enormously faster than a human. How does that affect our world? Well, hypothetically, the AI solves the protein folding problem. And then emails a DNA string to an online service that sequences the DNA , synthesizes the protein, and fedexes the protein back. The proteins self-assemble into a biological machine that builds a machine that builds a machine and then a few days later the AI has full-blown molecular nanotechnology.

Since this was written, AI has in fact solved the protein folding problem – which was considered the biggest problem in biology up to that point. But what’s this next step Yudkowsky mentions, molecular nanotechnology? Well, this is the third of Kurzweil’s three overlapping revolutions, along with biotechnology and AI. In short, the basic idea of nanotechnology is that as our overall level of technological development advances, so too does our capacity for technological precision – specifically our ability to build technologies that operate on smaller and smaller scales. (Recall, for instance, our earlier discussion of transistors being shrunk down to the nanometer scale.) Following this trend to its ultimate conclusion, we can expect that we’ll soon reach a point where we’re able to build machines so small that they can actually move around and manipulate individual atoms and molecules with ease. Once we’re able to build these microscopic machines (known as “nanobots” or “assemblers”), it’ll be possible to simply give them some raw materials, specify what we want them to assemble those raw materials into, and then sit back as they create whatever we want from scratch, like the replicators in Star Trek. And this really will mean whatever we want; as Yudkowsky explains:

Molecular nanotechnology is the dream of devices built out of individual atoms – devices that are actually custom-designed molecules. It’s the dream of infinitesimal robots, “assemblers”, capable of building arbitrary configurations of matter, atom by atom – including more assemblers. You only need to build one general assembler, and then in an hour there are two assemblers, and in another hour there are four assemblers. Fifty hours and a few tons of raw material later you have a quadrillion assemblers. Once you have your bucket of assemblers, you can give them molecular blueprints and tell them to build literally anything – cars, houses, spaceships built from diamond and sapphire; bread, clothing, beef Wellington… Or make changes to existing structures; remove arterial plaque, destroy cancerous cells, repair broken spinal cords, regenerate missing legs, cure old age…

It’s no exaggeration to say that once we’re able to unlock this kind of nanotechnology – or build an AI intelligent enough to unlock it for us – it’ll give us the power to instantly create whatever material goods we might desire on demand, at the snap of our fingers. We’ll essentially be able to solve all our material problems and transform the world into a post-scarcity utopia overnight. Of course, whether we actually will do so, or whether we’ll screw things up and unwittingly destroy ourselves in the process (or create a misaligned AI that destroys us), is another question, and we’ll return to the risks involved in all this momentarily. But assuming we do manage to get things right, there really will be basically nothing that’s beyond our ability to accomplish with these technologies. Problems like poverty and hunger simply won’t exist anymore once we have machines that can transform masses of dirt and garbage into mansions and filet mignon and whatever else we might want. The issue of climate change, which we’ve struggled to deal with for decades and which has come to seem like an existential threat, will be trivially easy to solve once we have swarms of nanobots that can simply go up and remove all the excess carbon from the atmosphere. Even social dysfunctions like racism, sexism, transphobia, and prejudice against people with physical and mental disabilities will become moot once everyone is walking around with quadruple-digit IQs and the ability to reconfigure the atoms in their bodies to change their sex, skin color, and other physical features as casually as they might change outfits. As impossibly intractable as all these problems might seem today, with the right technologies they’ll simply become non-issues – and we’ll look back and wonder how we could have ever thought we had a better chance of solving them with mechanisms like politics and cultural change than with technology.

In fact, once we’ve unlocked ASI and nanotechnology, even the biggest existential challenges we face as physical beings – things like aging and natural death – will become solvable (assuming we haven’t already solved them with biotechnology). Once we’ve attained the ability to completely reshape our physical reality at will, even the most seemingly immutable and unchangeable problems associated with having physical bodies will become changeable. And ultimately, once we’ve equipped ourselves with the ability to interface our minds with our machines, even the notion of having to remain stuck in one physical body at all will become unthinkably outdated. As Urban writes:

Armed with superintelligence and all the technology superintelligence would know how to create, ASI would likely be able to solve every problem in humanity. Global warming? ASI could first halt CO2 emissions by coming up with much better ways to generate energy that had nothing to do with fossil fuels. Then it could create some innovative way to begin to remove excess CO2 from the atmosphere. Cancer and other diseases? No problem for ASI—health and medicine would be revolutionized beyond imagination. World hunger? ASI could use things like nanotech to build meat from scratch that would be molecularly identical to real meat—in other words, it would be real meat. Nanotech could turn a pile of garbage into a huge vat of fresh meat or other food (which wouldn’t have to have its normal shape—picture a giant cube of apple)—and distribute all this food around the world using ultra-advanced transportation. Of course, this would also be great for animals, who wouldn’t have to get killed by humans much anymore, and ASI could do lots of other things to save endangered species or even bring back extinct species through work with preserved DNA. ASI could even solve our most complex macro issues—our debates over how economies should be run and how world trade is best facilitated, even our haziest grapplings in philosophy or ethics—would all be painfully obvious to ASI.

But there’s one thing ASI could do for us that is so tantalizing, reading about it has altered everything I thought I knew about everything:

ASI could allow us to conquer our mortality.

A few months ago, I mentioned my envy of more advanced potential civilizations who had conquered their own mortality, never considering that I might later write a post that genuinely made me believe that this is something humans could do within my lifetime. But reading about AI will make you reconsider everything you thought you were sure about—including your notion of death.

Evolution had no good reason to extend our lifespans any longer than they are now. If we live long enough to reproduce and raise our children to an age that they can fend for themselves, that’s enough for evolution—from an evolutionary point of view, the species can thrive with a 30+ year lifespan, so there’s no reason mutations toward unusually long life would have been favored in the natural selection process. As a result, we’re what W.B. Yeats describes as “a soul fastened to a dying animal.” Not that fun.

And because everyone has always died, we live under the “death and taxes” assumption that death is inevitable. We think of aging like time—both keep moving and there’s nothing you can do to stop them. But that assumption is wrong. Richard Feynman writes:

It is one of the most remarkable things that in all of the biological sciences there is no clue as to the necessity of death. If you say we want to make perpetual motion, we have discovered enough laws as we studied physics to see that it is either absolutely impossible or else the laws are wrong. But there is nothing in biology yet found that indicates the inevitability of death. This suggests to me that it is not at all inevitable and that it is only a matter of time before the biologists discover what it is that is causing us the trouble and that this terrible universal disease or temporariness of the human’s body will be cured.

The fact is, aging isn’t stuck to time. Time will continue moving, but aging doesn’t have to. If you think about it, it makes sense. All aging is the physical materials of the body wearing down. A car wears down over time too—but is its aging inevitable? If you perfectly repaired or replaced a car’s parts whenever one of them began to wear down, the car would run forever. The human body isn’t any different—just far more complex.

Kurzweil talks about intelligent wifi-connected nanobots in the bloodstream who could perform countless tasks for human health, including routinely repairing or replacing worn down cells in any part of the body. If perfected, this process (or a far smarter one ASI would come up with) wouldn’t just keep the body healthy, it could reverse aging. The difference between a 60-year-old’s body and a 30-year-old’s body is just a bunch of physical things that could be altered if we had the technology. ASI could build an “age refresher” that a 60-year-old could walk into, and they’d walk out with the body and skin of a 30-year-old. Even the ever-befuddling brain could be refreshed by something as smart as ASI, which would figure out how to do so without affecting the brain’s data (personality, memories, etc.). A 90-year-old suffering from dementia could head into the age refresher and come out sharp as a tack and ready to start a whole new career. This seems absurd—but the body is just a bunch of atoms and ASI would presumably be able to easily manipulate all kinds of atomic structures—so it’s not absurd.

Kurzweil then takes things a huge leap further. He believes that artificial materials will be integrated into the body more and more as time goes on. First, organs could be replaced by super-advanced machine versions that would run forever and never fail. Then he believes we could begin to redesign the body—things like replacing red blood cells with perfected red blood cell nanobots who could power their own movement, eliminating the need for a heart at all. He even gets to the brain and believes we’ll enhance our brain activities to the point where humans will be able to think billions of times faster than they do now and access outside information because the artificial additions to the brain will be able to communicate with all the info in the cloud.

The possibilities for new human experience would be endless. Humans have separated sex from its purpose, allowing people to have sex for fun, not just for reproduction. Kurzweil believes we’ll be able to do the same with food. Nanobots will be in charge of delivering perfect nutrition to the cells of the body, intelligently directing anything unhealthy to pass through the body without affecting anything. An eating condom. Nanotech theorist Robert A. Freitas has already designed blood cell replacements that, if one day implemented in the body, would allow a human to sprint for 15 minutes without taking a breath—so you can only imagine what ASI could do for our physical capabilities. Virtual reality would take on a new meaning—nanobots in the body could suppress the inputs coming from our senses and replace them with new signals that would put us entirely in a new environment, one that we’d see, hear, feel, and smell.

Eventually, Kurzweil believes humans will reach a point when they’re entirely artificial; a time when we’ll look at biological material and think how unbelievably primitive it was that humans were ever made of that; a time when we’ll read about early stages of human history, when microbes or accidents or diseases or wear and tear could just kill humans against their own will; a time the AI Revolution could bring to an end with the merging of humans and AI. This is how Kurzweil believes humans will ultimately conquer our biology and become indestructible and eternal. […] And he’s convinced we’re gonna get there. Soon.

In a future with fully-realized ASI and nanotechnology, we won’t just have a bunch of cool superpowers. Yes, we’ll be able to do things like control our own aging and conjure up objects at will – and we’ll also be able to do things like shapeshift, fly through the sky like birds, give ourselves whole new senses (like being able to feel electromagnetic fields, being able to see around corners with echolocation, etc.), and more. But ultimately, all this stuff will just be the tip of the iceberg. Compared to the whole new universes of mental and emotional capacities that will become available to us when we’re able to augment our own minds, this whole classical world of physical objects and material experiences might well end up feeling comparatively uninteresting. Just imagine being able to think and feel the most incredible thoughts and feelings you can currently conceive – but multiplied across a thousand new dimensions of richness and complexity that you can’t currently conceive, on a scale millions of times greater than anything you’ve ever experienced in your life. That’s the kind of thing that would be possible with these technologies; and there’s practically no ceiling for how far we could take it. As Yudkowsky writes:

Unless you’ve heard of nanotechnology, it’s hard to appreciate the magnitude of the changes we’re talking about. Total control of the material world at the molecular level is what the conservatives in the futurism business are predicting.

Material utopias and wish fulfillment – biological immortality, three-dimensional Xerox machines, free food, instant-mansions-just-add-water, and so on – are a wimpy use of a technology that could rewrite the entire planet on the molecular level, including the substrate of our own brains. The human brain contains a hundred billion neurons, interconnected with a hundred trillion synapses, along which impulses flash at the blinding speed of… 100 meters per second. Tops.

If we could reconfigure our neurons and upgrade the signal propagation speed to around, say, a third of the speed of light, or 100,000,000 meters per second, the result would be a factor-of-one-million speedup in thought. At this rate, one subjective year would pass every 31 physical seconds. Transforming an existing human would be a bit more work, but it could be done. Of course, you’d probably go nuts from sensory deprivation – your body would only send you half a minute’s worth of sensory information every year. With a bit more work, you could add “uploading” ports to the superneurons, so that your consciousness could be transferred into another body at the speed of light, or transferred into a body with a new, higher-speed design. You could even abandon bodies entirely and sit around in a virtual-reality environment, chatting with your friends, reading the library of Congress, or eating three thousand tons of potato chips without exploding.

If you could design superneurons that were smaller as well as being faster, so the signals had less distance to travel… well, I’ll skip to the big finish: Taking 10^17 ops/sec as the figure for the computing power used by a human brain, and using optimized atomic-scale hardware, we could run the entire human race on one gram of matter, running at a rate of one million subjective years every second.

What would we be doing in there, over the course of our first trillion years – about eleven and a half days, real time? Well, with control over the substrate of our brains, we would have absolute control over our perceived external environments – meaning an end to all physical pain. It would mean an end to old age. It would mean an end to death itself. It would mean immortality with backup copies. It would mean the prospect of endless growth for every human being – the ability to expand our own minds by adding more neurons (or superneurons), getting smarter as we age. We could experience everything we’ve ever wanted to experience. We could become everything we’ve ever dreamed of becoming. That dream – life without bound, without end – is called Apotheosis.

You might think that all this is starting to sound borderline religious, with all these utopian claims about transcending our physical bodies and conquering death and so on. And yes, I’ll freely admit that it does carry more than a whiff of that flavor. All I can say in response, though, is that in this case the grandiosity of the claims frankly seems fully justified, because unlocking these technologies really would be tantamount to unlocking powers that were quite literally godlike. As Urban puts it:

If our meager brains were able to invent wifi, then something 100 or 1,000 or 1 billion times smarter than we are should have no problem controlling the positioning of each and every atom in the world in any way it likes, at any time—everything we consider magic, every power we imagine a supreme God to have will be as mundane an activity for the ASI as flipping on a light switch is for us. Creating the technology to reverse human aging, curing disease and hunger and even mortality, reprogramming the weather to protect the future of life on Earth—all suddenly possible. Also possible is the immediate end of all life on Earth. As far as we’re concerned, if an ASI comes to being, there is now an omnipotent God on Earth.

So what would be the culmination of all this? What’s it all building toward? Well, obviously it’s impossible to know for sure in advance; mere present-day humans like us wouldn’t be able to imagine the desires and intentions of a future superintelligence any better than a bunch of ants would be able to imagine our own desires and intentions. (That’s the whole idea of the Singularity – what’s on the other side of the looking glass is fundamentally unknowable.) But based on everything we’ve been talking about, it’s not hard to imagine one way things might go. It’s imaginable that as we continually augment our minds more and more, and integrate them more and more deeply with our machines, we’ll eventually come to a point where we’ve completely digitized our brains and uploaded them into the cloud – which, in this case, wouldn’t just be a metaphorical term for the internet, but an actual, literal cloud of trillions upon trillions of nanobots covering the planet and forming the substrate for all of human consciousness. Having uploaded ourselves into a digital format like this, we’d not only gain the ability to use the nanobots to manifest whatever physical reality we might want; we’d also gain the ability to directly interface with other minds that had similarly uploaded themselves – to share consciousnesses, to experience others’ thoughts and feelings firsthand, even to combine our minds with theirs if we so desired. We’d be able to experience transcendent levels of bliss and communion with each other and with the broader universe far beyond anything we can currently imagine. And eventually, we’d either reach a point of absolute, perfect fulfillment – at which point we’d live happily ever after and that would be the end of our story – or we’d just continue growing in our capacities, and our story would keep going indefinitely. As our self-augmentation continued, our ubiquitous cloud-consciousness would extend further and further out into space to seek out more and more raw material for us to convert into computational substrate, until ultimately we had spread across the entire universe, and our collective consciousness had become a (quite literally) universal consciousness. As Lev Grossman summarizes:

In Kurzweil’s future, biotechnology and nanotechnology give us the power to manipulate our bodies and the world around us at will, at the molecular level. Progress hyperaccelerates, and every hour brings a century’s worth of scientific breakthroughs. We ditch Darwin and take charge of our own evolution. The human genome becomes just so much code to be bug-tested and optimized and, if necessary, rewritten. Indefinite life extension becomes a reality; people die only if they choose to. Death loses its sting once and for all. Kurzweil hopes to bring his dead father back to life.

We can scan our consciousnesses into computers and enter a virtual existence or swap our bodies for immortal robots and light out for the edges of space as intergalactic godlings. Within a matter of centuries, human intelligence will have re-engineered and saturated all the matter in the universe. This is, Kurzweil believes, our destiny as a species.

Or as commenter VelveteenAmbush more poetically puts it:

These are the things that, if all goes well, will eventually lift humanity to the heavens, slay the demons (disease, death, etc.) that have haunted us forever, and awaken the dead matter of the cosmos into flourishing sentience.

Again, this will all undoubtedly sound like the most unbelievable kind of science fiction to anyone who’s not familiar with the current scientific understanding of AI and nanotechnology and all the rest. Frankly, these are some pretty extraordinary claims, so some degree of disbelief is entirely understandable. That being said, though, the crucial thing to understand here is that the kinds of technologies we’ve been discussing aren’t just speculations of distant future possibilities; they’re already being developed and refined today. As impossible as it might sound, for instance, to have a machine that can precisely move around individual atoms and molecules, the most rudimentary version of this technology has actually existed since the 1980s, when scientists used such a machine to spell out the IBM logo with individual atoms. The proof of concept, in other words, is no longer in question, and hasn’t been for decades. It’s now just a matter of scientists continuing to refine the technology until they’ve worked out a functional design for the first nanoscale molecular assembler – and once they’ve done that, the assembler itself can take over the rest of the way and build more assemblers, which can themselves build more assemblers, and so on. They’ve actually already figured out how to build autonomous self-replicating machines like this on a macro scale (here’s an early prototype from 2002, for instance, which was built out of Lego bricks); their next step at this point is just to continually improve the designs (and the techniques for miniaturizing them) until such assemblers can be made on the most microscopic scales possible – a task that, even if it proves too difficult for humans to finish in these next few years, will be easy for an advanced AI.

Likewise, AI itself is another technology that’s no longer fictional. Not only have we developed AIs that now seem to be right on the verge of breaking through into general intelligence; we’ve also made enough progress on the hardware side that if and when we finally do unlock full ASI, we’ll already have sufficient hardware to support it. As Yudkowsky points out, the only major hurdles left at this point are the ones on the software side – and that’s an area where we could quite literally have a transformative breakthrough that pushes us the rest of the way to the finish line at any moment (especially with increasingly advanced coding AIs helping with the task):

Since the Internet exploded across the planet, there has been enough networked computing power for intelligence. If [a portion of] the Internet were properly reprogrammed, [or if we just used one of the supercomputers that now exist,] it would be enough to run a human brain, or a seed AI. On the nanotechnology side, we possess machines capable of producing arbitrary DNA sequences, and we know how to turn arbitrary DNA sequences into arbitrary proteins (You open up a bacterium, insert the DNA, and let the automatic biomanufacturing facility go to work). We have machines – Atomic Force Probes – that can put single atoms anywhere we like, and which have recently [1999] been demonstrated to be capable of forming atomic bonds. Hundredth-nanometer precision positioning, atomic-scale tweezers… the news just keeps on piling up.

If we had a time machine, 100K of information from the future could specify a protein that built a device that would give us nanotechnology overnight. 100K could contain the code for a seed AI. Ever since the late 90’s, the Singularity has been only a problem of software. And software is information, the magic stuff that changes at arbitrarily high speeds. As far as technology is concerned, the Singularity could happen tomorrow. One breakthrough – just one major insight – in the science of protein engineering or atomic manipulation or Artificial Intelligence, one really good day at [an AI company or nanotechnology research program], and the door to Singularity sweeps open.

Needless to say, the Singularity probably won’t happen literally tomorrow. But even so, there’s a genuinely good chance that it will happen very, very soon. We’re talking years, not centuries – maybe not even decades. Kurzweil’s original prediction, back in 2005, was that we’d reach the Singularity sometime around 2045 – a prediction that, to put it mildly, was met with heavy skepticism at the time. But as the pace of AI development has accelerated, more and more AI experts have begun to converge on the conclusion that actually, that might not have been such an unreasonable estimate after all – and in fact we may even get ASI before then. In recent polls of AI experts (as briefly referenced earlier), the most popular estimates for the date of the Singularity have been right in line with Kurzweil’s timeframe, somewhere in the 2030s-50s (and increasingly many are starting to lean toward the lower end of that range). Of course, that’s not to say that everything will go exactly as he predicted; in the 20 years since his book was published, we’ve already seen that many of his predictions regarding specific technologies and their development timelines have turned out to be off-base. (He expected, for instance, that VR and nanotechnology would advance more rapidly than AI, when in fact it’s been the other way around.) Nevertheless, his broader thesis about the acceleration of information technology as a whole – and his predicted timeline for this general trend – has held up remarkably well. At this point, the emerging consensus among experts is that it would be more surprising if we didn’t reach the Singularity within the next few decades than if we did. And even among the skeptics, the biggest criticism of Kurzweil’s ideas is no longer that they’re completely implausible, but just that his timeline is overly optimistic; that is, they’re no longer disagreeing so much that all this stuff will eventually happen – they’re mostly just disagreeing about when it’ll happen. As Urban writes:

You will not be surprised to learn that Kurzweil’s ideas have attracted significant criticism. His prediction of 2045 for the singularity and the subsequent eternal life possibilities for humans has been mocked as “the rapture of the nerds,” or “intelligent design for 140 IQ people.” Others have questioned his optimistic timeline, or his level of understanding of the brain and body, or his application of the patterns of Moore’s law, which are normally applied to advances in hardware, to a broad range of things, including software.

[…]

But what surprised me is that most of the experts who disagree with him don’t really disagree that everything he’s saying is possible. Reading such an outlandish vision for the future, I expected his critics to be saying, “Obviously that stuff can’t happen,” but instead they were saying things like, “Yes, all of that can happen if we safely transition to ASI, but that’s the hard part.” [Nick] Bostrom, one of the most prominent voices warning us about the dangers of AI, still acknowledges:

It is hard to think of any problem that a superintelligence could not either solve or at least help us solve. Disease, poverty, environmental destruction, unnecessary suffering of all kinds: these are things that a superintelligence equipped with advanced nanotechnology would be capable of eliminating. Additionally, a superintelligence could give us indefinite lifespan, either by stopping and reversing the aging process through the use of nanomedicine, or by offering us the option to upload ourselves. A superintelligence could also create opportunities for us to vastly increase our own intellectual and emotional capabilities, and it could assist us in creating a highly appealing experiential world in which we could live lives devoted to joyful game-playing, relating to each other, experiencing, personal growth, and to living closer to our ideals.

This is a quote from someone very much not [in the optimistic camp], but that’s what I kept coming across—experts who scoff at Kurzweil for a bunch of reasons but who don’t think what he’s saying is impossible if we can make it safely to ASI. That’s why I found Kurzweil’s ideas so infectious—because they articulate the bright side of this story and because they’re actually possible. If [everything goes right].

Of course, as optimistic as Kurzweil’s outlook is, you might have some reservations about all this yourself – or at least some questions. For instance, even if we accept that everything discussed above actually is possible (which, granted, is a lot to accept), what’s all this about “uploading ourselves into the cloud”? What would that even entail? Sure, augmenting our brains with things like extra storage capacity and faster processing speed might be all well and good, but how would it even be possible to transfer a person’s entire mind into a computational substrate? Wouldn’t it basically just amount to copying their brain onto a computer, while still leaving the original biological brain outside (where it would eventually grow old and die as usual)? Well, not necessarily. Certainly, you could simply make a virtual duplicate of your brain if that’s all you wanted, just in order to have it on hand as a backup copy or what have you. But if what you wanted was to actually fully convert your biological brain into a non-biological one, that would involve a different kind of procedure. Yudkowsky briefly touched on this a moment ago, but just to expand on what he said, it might involve (say) using nanotechnology to gradually replace the neurons in your brain with artificial ones, in much the same way that your body is constantly replacing your cells with new ones as they die. You’d start with just replacing one single neuron (which you wouldn’t even notice, since your brain has tens of billions of neurons in total), and then after that, you’d replace another one in the same way, and then another one, and another one, and so on – until gradually, over the course of several days or weeks or months, you’d replaced all your neurons with artificial ones, Ship of Theseus-style. These artificial neurons would still be performing all the same functions as the old biological ones as soon as they were swapped in, so your mind would remain intact throughout this entire process; your brain would still continue functioning normally without any interruption in your consciousness, so you’d still be “you” the whole time. It’s just that more and more of your neural processing would be done by the artificial neurons, until eventually you’d transformed your brain from 100% soft tissue to 100% machine. Once that was done, your brain would be able to connect directly to the digital world, and you’d be able to absorb all of humanity’s knowledge and tap into limitless virtual realities and experience ultimate transcendent fulfillment and all the rest – and because your mind was now encoded in a format that wasn’t subject to biological aging or natural death, you’d be able to continue doing so for as long as you wanted.

But maybe all this talk of becoming all-powerful and immortal doesn’t exactly sit right with you either. Maybe you’re the kind of person who thinks that mortality is a good thing – that “death is just a part of life,” and that the inevitability of death is what gives life meaning – so you wouldn’t want to live longer than your “natural” lifespan of 80 years or so. This is a fairly common sentiment, and it’s certainly the type of idea that many people think sounds profound – but to be honest, I personally think it’s disastrously misguided. I think that most people, even if they claimed they wouldn’t want to live past 80 or so, would actually prefer not to die if you approached them on their 80th birthday, held a gun to their head, and gave them the choice between either instant death or continuing to live another year with a healthy, youthful body (as they’d be able to do with future technology). Unless they were literally suicidal, I think that every year you repeated this, they’d keep choosing to live another year. And I think they’d be right to do so. I think the idea that “death is what gives life meaning” is, frankly, nothing but a rationalization – something that we convince ourselves is true in order to feel better about our own mortality. If not dying were actually an option, I suspect we’d suddenly find that in fact, our lives still contained plenty of meaning, and that we wouldn’t want to lose them. As Yudkowsky puts it:

Given human nature, if people got hit on the head by a baseball bat every week, pretty soon they would invent reasons why getting hit on the head with a baseball bat was a good thing. But if you took someone who wasn’t being hit on the head with a baseball bat, and you asked them if they wanted it, they would say no. I think that if you took someone who was immortal, and asked them if they wanted to die for benefit X, they would say no.

Indeed, it seems telling that you don’t hear many people today advocating for our lifespans to be shorter, on the basis that that would make them more meaningful, or that it would be more “natural” and therefore better. As Michael Finkel writes (quoting de Grey):

To those who say that [anti-aging research] is attempting to meddle in God’s realm, de Grey points out that for most of human history, life expectancy was probably no more than twenty years. Should we not have increased it?

Some people might respond that this isn’t the same thing as the kind of radical life extension we’re talking about – that living for 80 years might be fine, but that living for centuries would be more of a curse than a blessing, because eventually we’d run out of things to do and we’d become so bored that we’d lose the will to live. But there are a couple of counterpoints to this argument. Firstly, in the scenario we’ve been discussing, nobody would be making anybody else live any longer than they wanted to; if somebody got tired of living and decided to hang it up, they’d be perfectly free to do so. All that would really change with radical life extension is that anyone who didn’t want to die would be able to keep living for as long as they wanted, and would only have to die when they were ready. Secondly, though, the idea that people would want to do so after just 80 years – that in a world where everyone had the power to create whatever reality they wanted to create and to be whoever or whatever they wanted to be, they’d “run out of things to do” after a mere eight decades – seems to reflect more of a lack of imagination than anything. With nanotechnology and ASI at their disposal, the list of things people could do would be quite literally endless. And if nothing else, even if someone did somehow manage (after a few millennia or so) to experience literally everything they’d ever dreamed of, and couldn’t think of anything else to do, they could always just selectively erase their memories and re-live those same experiences all over again, and get just as much joy and satisfaction out of them as they did the first time. Or alternatively, they could simply set the joy and satisfaction centers of their brain to maximum levels, and live out the rest of time as enlightened Buddha-like beings of perfect contentment and fulfillment – i.e. the kind of ultimate fate that, in a religious context, would be called “nirvana” or “Heaven.” (See Alexander’s posts on the subject here and here.) Do we really think this would be a worse outcome than dying in a hospital at 80? Unless you actually do believe in some kind of religious afterlife, it’s not exactly an easy case to make (and even in that case, you’d presumably believe that the afterlife was eternal and wasn’t going anywhere regardless – so what would be the big rush to get there?).

In sum, I’ll just copy-paste two pieces here that I originally included in my earlier post on religion. The first is this short video from CGP Grey, which perfectly encapsulates how I feel about the whole matter:

And the second is this poem by Edna St. Vincent Millay, “Dirge Without Music,” which captures the emotional thrust of it even more powerfully:

I am not resigned to the shutting away of loving hearts in the hard ground.

So it is, and so it will be, for so it has been, time out of mind:

Into the darkness they go, the wise and the lovely. Crowned

With lilies and with laurel they go; but I am not resigned.Lovers and thinkers, into the earth with you.

Be one with the dull, the indiscriminate dust.

A fragment of what you felt, of what you knew,

A formula, a phrase remains, – but the best is lost.The answers quick and keen, the honest look, the laughter, the love, –

They are gone. They are gone to feed the roses. Elegant and curled

Is the blossom. Fragrant is the blossom. I know. But I do not approve.

More precious was the light in your eyes than all the roses in the world.Down, down, down into the darkness of the grave

Gently they go, the beautiful, the tender, the kind;

Quietly they go, the intelligent, the witty, the brave.

I know. But I do not approve. And I am not resigned.

This is, in my view, the appropriate attitude to take toward death. Human life is a beautiful and precious thing – and every time a life is snuffed out, it’s a tragedy. (Even if the death is voluntary, that too is tragic for its own reasons.) Yes, death is a part of life. It’s the worst part. And it doesn’t have to keep being a part of life. If we put our minds to it, we can stop it – and we absolutely should.

I realize that not everyone will be on board with all this. You might not naturally find it easy to embrace this kind of thing yourself, just in terms of your basic personality or temperament or whatever. You might not want anything to do with any of this. And if you don’t, well, it’s like I said – nobody will force you to go along with any of it. You won’t have to extend your life, or enhance your brain, or upload your consciousness, or participate in any of this if you don’t want to; you’ll always have the option of just living out your normal human life until you die a natural death at the end of your natural lifespan. You should just be aware, though, that while you as an individual will have the choice of opting out if that’s what you want, you won’t be able to make that same choice for humanity as a whole. For humanity as a whole, the Singularity is coming, whether you personally are on board with it or not. As Yudkowsky puts it:

Maybe you don’t want to see humanity replaced by a bunch of “machines” or “mutants”, even superintelligent ones? You love humanity and you don’t want to see it obsoleted? You’re afraid of disturbing the natural course of existence?

Well, tough luck. The Singularity is the natural course of existence. Every species – at least, every species that doesn’t blow itself up – sooner or later comes face-to-face with a full-blown superintelligence. It happens to everyone. It will happen to us. It will even happen to the first-stage transhumans [i.e. augmented humans] or the initial human-equivalent AIs.

But just because humans become obsolete doesn’t mean you become obsolete. You are not a human. You are an intelligence which, at present, happens to have a mind unfortunately limited to human hardware. That could change. With any luck, all persons on this planet who live to 2035 […] or whenever – and maybe some who don’t – will wind up as [post-Singularity transhumans].

Again, you won’t have to come along for the ride if you don’t want to. But I would just suggest being open to the possibility that, for the same reasons you don’t want to die right now, you won’t want to die when you’re older either – and for the same reasons you want to get smarter and more capable and happier now, you’ll want to get smarter and more capable and happier in the future, and so on. It might also be worth reading this short story by Marc Stiegler called “The Gentle Seduction,” which describes how accepting all of this might actually turn out to be more natural than you’d think. If nothing else, it’s at least something to think about – because in all likelihood, it will become a much more immediate question very soon.