I – II – III – IV – V – VI – VII – VIII – IX – X – XI – XII – XIII – XIV – XV – XVI – XVII – XVIII – XIX – XX – XXI – XXII – XXIII – XXIV – XXV – XXVI – XXVII – XXVIII – XXIX

[Single-page view]

Fine then, maybe the big corporations and their high-earning executives are mostly acting in accordance with basic market forces, and aren’t all just purely evil predators. But what about that other group of much-reviled capitalists – their financiers (i.e. the bankers and stockholders and so on)? Surely those people are the ones who really are just operating in a mode of pure predation, right? Aren’t they the real problem?

This has always been a widespread sentiment – so much so that, as Steven Pinker points out, it can often get downright nasty:

Commercial activities, which tend to be concentrated in cities, can themselves be triggers of moralistic hatred. […] People’s intuitive sense of economics is rooted in tit-for-tat exchanges of concrete goods or services of equivalent value—say, three chickens for one knife. It does not easily grasp the abstract mathematical apparatus of a modern economy, such as money, profit, interest, and rent. In intuitive economics, farmers and craftsmen produce palpable items of value. Merchants and other middlemen, who skim off a profit as they pass goods along without causing new stuff to come into being, are seen as parasites, despite the value they create by enabling transactions between producers and consumers who are unacquainted or separated by distance. Moneylenders, who loan out a sum and then demand additional money in return, are held in even greater contempt, despite the service they render by providing people with money at times in their lives when it can be put to the best use. People tend to be oblivious to the intangible contributions of merchants and moneylenders and view them as bloodsuckers. […] Antipathy toward individual middlemen can easily transfer to antipathy to ethnic groups. The capital necessary to prosper in middlemen occupations consists mainly of expertise rather than land or factories, so it is easily shared among kin and friends, and it is highly portable. For these reasons it’s common for particular ethnic groups to specialize in the middleman niche and to move to whatever communities currently lack them, where they tend to become prosperous minorities—and targets of envy and resentment. Many victims of discrimination, expulsion, riots, and genocide have been social or ethnic groups that specialize in middlemen niches. They include various bourgeois minorities in the Soviet Union, China, and Cambodia, the Indians in East Africa and Oceania, the Ibos in Nigeria, the Armenians in Turkey, the Chinese in Indonesia, Malaysia, and Vietnam, and the Jews in Europe.

Despite how popular it is to despise bankers and other financiers, the idea that bankers are “the problem” comes from a deep misunderstanding of their role in economy. Without the services they provide, our entire economic system would fall apart. What exactly are these crucial services they provide? Well, just to start with the simplest and most obvious one, banks are the most efficient way of keeping our money secure. As Sowell writes:

Why are there banks in the first place?

One reason is that there are economies of scale in guarding money. If restaurants or hardware stores kept all the money they received from their customers in a back room somewhere, criminals would hold up far more restaurants, hardware stores, and other businesses and homes than they do. By transferring their money to a bank, individuals and enterprises are able to have their money guarded by others at lower costs than guarding it themselves.

Banks can invest in vaults and guards, or pay to have armored cars come around regularly to pick up money from businesses and take it to some other heavily guarded place for storage. In the United States, Federal Reserve Banks store money from private banks and money and gold owned by the U.S. government. The security systems there are so effective that, although private banks get robbed from time to time, no Federal Reserve Bank has ever been robbed. Nearly half of all the gold owned by the German government was at one time stored in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. In short, economies of scale enable banks to guard wealth at lower costs per unit of wealth than either private businesses or homes, and enable the Federal Reserve Banks to guard wealth at lower costs per unit of wealth than private banks.

But protecting deposits isn’t the only reason (or even the main reason) why banks are so important. Their most critical function is taking those deposits and lending them back out again to borrowers. As Wheelan stresses, this is the thing that truly justifies the existence not only of traditional banks, but of all kinds of other bank-like financial institutions as well:

First, and perhaps most important, banks are good. Yes, [there is the risk of] crashes and bailouts [when things don’t function properly], but let us not lose sight of the profound economic benefits that stem from matching lenders with borrowers. I am using “bank” in the broadest sense of the word. For regulatory and legal purposes, a bank is different from a savings and loan, which is different from a hedge fund or the money market or the repurchase agreement market. Finance is steadily evolving (often in response to the regulations imposed after the last financial crisis). The “shadow banking” sector represents a large and growing group of nondepository institutions that borrow and lend, albeit with less regulation than traditional banks and without taking consumer deposits. These institutions have the same advantages and vulnerabilities as George Bailey’s Building and Loan. For our purposes here, if it lends like a bank, and it borrows like a bank, then it’s a bank. The Economist has described these collective institutions as an “economic time machine, helping savers transport today’s surplus income into the future, or giving borrowers access to future earnings now.” In the process, they scour the globe for investment opportunities, moving capital to wherever it can be used most productively. This is right up there with electricity and antibiotics in terms of making our lives better. Really.

Alexander elaborates on the “economic time machine” analogy, illustrating how the ability to borrow money allows individuals and businesses to create new value and accomplish things that they simply wouldn’t have been able to accomplish otherwise:

Actually, all stock exchanges are about [creating] slack [for borrowers]. Imagine you are a brilliant inventor who, given $10 million and ten years, could invent fusion power. But in fact you have $10 and need work tomorrow or you will starve. Given those constraints, maybe you could start, I don’t know, a lemonade stand.

You’re in the same position as [an] animal trying to evolve an eye [in a hyper-competitive evolutionary environment with no room for any metabolic waste] – you could create something very high-utility, if only you had enough slack to make it happen. But by default, the inventor working on fusion power starves to death tomorrow (or at least makes less money than his counterpart who ran the lemonade stand), the same way the animal who evolves Eye Part 1 gets outcompeted by other animals who didn’t and dies out.

You need slack. In the evolution example, animals usually stumble across slack randomly. You too might stumble across slack randomly – maybe it so happens that you are independently wealthy, or won the lottery, or something.

More likely, you use the investment system. You ask rich people to give you $10 million for ten years so you can invent fusion; once you do, you’ll make trillions of dollars and share some of it with them.

This is a great system. There’s no evolutionary equivalent. An animal can’t pitch Darwin on its three-step plan to evolve eyes and get free food and mating opportunities to make it happen. Wall Street is a giant multi-trillion dollar time machine funneling future profits back into the past, and that gives people the slack they need to make the future profits happen at all.

The key point here is that in order to create new wealth by providing some new product, you first need to pay for all the costs of producing it; you can’t produce the product first and then only pay the costs of producing it afterwards. At least, you wouldn’t be able to do this on your own. But having a financier like a bank or an investment group allows you to basically do exactly that, by giving you the necessary money up front (for a small fee) and then having you pay it back later once you’ve used it to create even more new wealth. As Steve Keen writes (quoting Basil Moore):

Businesses need credit in order to be able to meet their costs of production prior to receiving sales receipts, and this is the fundamental beneficial role of banks in a capitalist economy:

In modern economies production costs are normally incurred and paid prior to the receipt of sales proceeds. Such costs represent a working capital investment by the firm, for which it must necessarily obtain finance. Whenever wage or raw materials price increases raise current production costs, unchanged production flows will require additional working capital finance. In the absence of instantaneous replacement cost pricing, firms must finance their increased working capital needs by increasing their borrowings from their banks or by running down their liquid assets. (Moore 1983, p. 545)

Banks therefore accommodate the need that businesses have for credit via additional lending—and if they did not, ordinary commerce would be subject to Lehman Brothers-style credit crunches on a daily basis.

And the ability to borrow money isn’t just good for businesses seeking to pay for their present-day expenses with their future income; it’s also good for regular people seeking to do the same thing for their personal expenses. As Wheelan writes:

Financial markets do more than take capital from the rich and lend it to everyone else. They enable each of us to smooth consumption over our lifetimes, which is a fancy way of saying that we don’t have to spend income at the same time we earn it. Shakespeare may have admonished us to be neither borrowers nor lenders; the fact is that most of us will be both at some point. If we lived in an agrarian society, we would have to eat our crops reasonably soon after the harvest or find some way to store them. Financial markets are a more sophisticated way of managing the harvest. We can spend income now that we have not yet earned—as by borrowing for college or a home—or we can earn income now and spend it later, as by saving for retirement. The important point is that earning income has been divorced from spending it, allowing us much more flexibility in life.

And this principle even applies to entire nations, as Garett Jones notes:

Governments want to be able to borrow for construction projects and other infrastructure investments. Furthermore, if worker productivity continues to increase at a rate of 1% or so per year, it makes good economic sense to borrow against some of the nation’s future income every year, to live a little better now and repay that debt when you’re richer a few decades from now. After all, if your nation will be earning 50% more per person in five decades, why not use the power of the global financial markets to pull some of the prosperity forward in time? Just as youth is wasted on the young, so is income wasted on the old. We can’t do much about the former, but financial markets can help the younger me enjoy some the wealth that the older me will someday receive.

This is the value of banking. By taking money that isn’t being used for anything else, and putting it in the hands of borrowers who can actually make good use of it, lenders can make everyone better off. Wheelan sums up the whole process with a simple analogy:

[Imagine] a hypothetical rural society sustained primarily by rice farming [in which rice, rather than paper money, is used as currency].

[…]

The proprietors of the rice storehouses [the equivalent of banks in this scenario] will undoubtedly observe over time that most people with accounts do not show up to demand their rice. Instead, the deposits and withdrawals ebb and flow in a predictable pattern. What a waste! All this potentially productive rice locked away, just attracting rats. So let’s introduce an enterprising storehouse owner who realizes that he can make a profit by loaning out bags of rice from the vault while they are sitting there idle.

[…]

These loans have the potential to make all parties better off. New farmers can get started by borrowing rice to plant, which they will repay with interest after the harvest. The borrowers offer collateral, such as the title to their land, so the storehouses will be compensated in the event of default. Meanwhile, families with surplus rice can earn a small sum for keeping their rice in the vault, whereas previously they had to pay a storage fee. The rice banker makes a profit by acting as the intermediary between rice lenders and rice borrowers. Banking really does make our Norman Rockwell-inspired hamlet better off—just as it has everywhere else, for all of history. As the Economist has noted, “The rise of banking has often been accompanied by a flowering of civilization.”

Now, naturally, another thing that has been a constant throughout history is popular criticism of the whole process. What right, critics ask, do rich lenders have to demand that borrowers pay them a fee (i.e. interest) just for using funds that would otherwise be sitting idle? This is an understandable sentiment – but the simple response is that if borrowers weren’t paying them some kind of fee, the lenders wouldn’t have any economic reason to loan the funds in the first place; they’d just hold on to them and save them for a rainy day (or put them to use elsewhere). In order to induce lenders to loan the funds at all, then, borrowers have to be willing to offer them a better alternative. It’s the same principle that we keep coming back to over and over again: Giving somebody money in a transaction (in this case, paying them interest on a loan) isn’t a matter of whether or not they innately “deserve” to receive it; it’s an incentive to get them to provide a particular good or service (in this case the loan) in the first place. Again, it’s a price just like any other price. And so for this reason, the fact that lenders profit from their loans should be just as unsurprising to us as the fact that any other kind of seller profits from selling anything else. As Lars A. Doucet writes:

Remember that capital is wealth devoted to getting more wealth. So if capital is wealth that begets wealth, it makes sense that if I lend it out to you, I miss out on the potential for it to grow while it’s out of my hands. [It’s therefore logical, in economic terms, to claim that] I am justly entitled to ask for more back than I originally gave you.

Let’s say I loan you some corn seeds for a season. Had I not lent them to you, in a season’s time I could have grown my own crop of corn and been left with more seed than I started with. So in a perfectly square deal, you need to give me back what I started with and what I could have expected to gain from natural increase (less the value of the labor required to get things started).

Likewise with any other article of capital – say bricks or lumber. In the time I’ve spent without it while it was in your possession, I could have found someone else who had a better use for it than I did and exchanged it for something of theirs that I had a better use for, leaving me with capital of greater value.

A lender demanding interest on a loan, then – whether it be a loan of corn seeds, bricks, lumber, or dollar bills – makes perfect economic sense, for the same reason that it makes perfect economic sense for them to want all their other transactions to leave them better off rather than worse off. If they thought that an economic transaction would leave them worse off, then (unless it was a pure act of charity) they simply wouldn’t do it. This isn’t some kind of cynical Machiavellian calculation; it’s just how rational self-interest works. And in fact, the same logic underlies every other kind of “investment” people make in different areas of life – not just lenders deciding whether to invest in a particular person or business, but workers deciding whether to invest in learning a particular skill, students deciding whether to invest in getting a degree, and so on. As Sowell writes:

A tourist in New York’s Greenwich Village decided to have his portrait sketched by a sidewalk artist. He received a very fine sketch, for which he was charged $100.

“That’s expensive,” he said to the artist, “but I’ll pay it, because it is a great sketch. But, really, it took you only five minutes.”

“Twenty years and five minutes,” the artist replied.

Artistic ability is only one of many things which are accumulated over time for use later on. Some people may think of investment as simply a transaction with money. But, more broadly and more fundamentally, it is the sacrificing of real things today in order to have more real things in the future.

In the case of the Greenwich Village artist, it was time that was invested for two decades, in order to develop the skills that allow a striking sketch to be made in five minutes. For society as a whole, investment is more likely to take the form of foregoing the production of some consumer goods today so that the labor and capital that would have been used to produce those consumer goods will be used instead to produce machinery and factories that will cause future production to be greater than it would be otherwise. The accompanying financial transactions may be what the attention of individual investors are focused on but here, as elsewhere, for society as a whole money is just an artificial device to facilitate real things that constitute real wealth.

Because the future cannot be known in advance, investments necessarily involve risks, as well as the tangible things that are invested. These risks must be compensated if investments are to continue. The cost of keeping people alive while waiting for their artistic talent to develop, their oil explorations to finally find places where oil wells can be drilled, or their academic credits to eventually add up to enough to earn their degrees, are all investments that must be repaid if such investments are to continue to be made.

The repaying of investments is not a matter of morality, but of economics. If the return on the investment is not enough to make it worthwhile, fewer people will make that particular investment in the future, and future consumers will therefore be denied the use of the goods and services that would otherwise have been produced.

No one is under any obligation to make all investments pay off, but how many need to pay off, and to what extent, is determined by how many consumers value the benefits of other people’s investments, and to what extent.

Where the consumers do not value what is being produced, the investment should not pay off. When people insist on specializing in a field for which there is little demand, their investment has been a waste of scarce resources that could have produced something else that others wanted. The low pay and sparse employment opportunities in that field are a compelling signal to them—and to others coming after them—to stop making such investments.

The principles of investment are involved in activities that do not pass through the marketplace, and are not normally thought of as economic. Putting things away after you use them is an investment of time in the present to reduce the time required to find them in the future. Explaining yourself to others can be a time-consuming, and even unpleasant, activity but it is engaged in as an investment to prevent greater unhappiness in the future from avoidable misunderstandings.

Again, the common thread in all these activities that if someone is making an investment in something, they’re doing so specifically because they expect to get more out of it than what they’re putting in. If this weren’t the case, they wouldn’t be doing it in the first place. So given this fact, then – that some return will always be expected on any investment – the next question that naturally arises is how exactly to determine what the amount of that return will be. To answer that question, here’s Keen again, citing the work of Irving Fisher:

In 1930 Fisher published The Theory of Interest, which asserted that the interest rate ‘expresses a price in the exchange between present and future goods’ (Fisher 1930).

[…]

Fisher’s model had three components: the subjective preferences of different individuals between consuming more now by borrowing, or consuming more in the future by forgoing consumption now and lending instead; the objective possibilities for investment; and a market which reconciled the two. From the subjective perspective, a lender of money is someone who, compared to the prevailing rate of interest, has a low time preference for present over future goods. Someone who would be willing to forgo $100 worth of consumption today in return for $103 worth of consumption next year has a rate of time preference of 3 percent. If the prevailing interest rate is in fact 6 percent, then by lending out $100 today, this person enables himself to consume $106 worth of commodities next year, and has clearly made a personal gain. This person will therefore be a lender when the interest rate is 6 percent.

Conversely, a borrower is someone who has a high time preference for present goods over future goods. Someone who would require $110 next year in order to be tempted to forgo consuming $100 today would decide that, at a rate of interest of 6 percent, it was worth his while to borrow. That way, he can finance $100 worth of consumption today, at a cost of only $106 worth of consumption next year. This person will be a borrower at an interest rate of 6 percent.

The act of borrowing is thus a means by which those with a high preference for present goods acquire the funds they need now, at the expense of some of their later income.

Individual preferences themselves depend in part upon the income flow that an individual anticipates, so that a wealthy individual, or someone who expects income to fall in the future, is likely to be a lender, whereas a poor individual, or one who expects income to rise in the future, is likely to be a borrower.

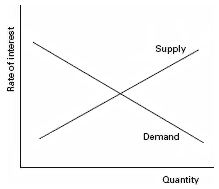

At a very low rate of interest, even people who have a very low time preference are unlikely to lend money, since the return from lending would be below their rate of time preference. At a very high rate of interest, even those who have a high time preference are likely to be lenders instead, since the high rate of interest would exceed their rate of time preference. This relationship between the rate of interest and the supply of funds gives us an upward-sloping supply curve for money.

The objective perspective reflects the possibilities for profitable investment. At a high rate of interest, only a small number of investment projects will be expected to turn a profit, and therefore investment will be low. At a low rate of interest, almost all projects are likely to turn a profit over financing costs, so the demand for money will be very high. This relationship between the interest rate and the demand for money gives us a downward-sloping demand curve for money.

The market mechanism brings these two forces into harmony by yielding the equilibrium rate of interest.

Sowell provides some additional explanation, adding that this calculus can become more complicated when the additional factor of taxation is introduced into the mix:

Leaving inflation aside, how much would a $10,000 bond that matures a year from now be worth to you today? That is, how much would you bid today for a bond that can be cashed in for $10,000 next year? Clearly it would not be worth $10,000, because future money is not as valuable as the same amount of present money. Even if you felt certain that you would still be alive a year from now, and even if there were no inflation expected, you would still prefer to have the same amount of money right now rather than later. If nothing else, money that you have today can be put in a bank and earn a year’s interest on it. For the same reason, if you had a choice between buying a bond that matures a year from now and another bond of the same face value that matures ten years from now, you would not be willing to bid as much for the one that matures a decade later.

What this says is that the same nominal amount of money has different values, depending on how long you must wait to receive it. At a sufficiently high interest rate, you might be willing to wait decades to get your money back. People buy 30-year bonds regularly, though usually at a higher rate of return than what is paid on financial securities that mature in a year. On the other hand, at a sufficiently low interest rate, you would not be willing to wait any time at all to get your money back.

Somewhere in between is an interest rate at which you would be indifferent between lending money or keeping it. At that interest rate, the present value of a given amount of future money is equal to some smaller amount of present money. For example if you are indifferent at 4 percent, then a hundred dollars today is worth $104 a year from now to you. Any business or government agency that wants to borrow $100 from you today with a promise to pay you back a year from now will have to make that repayment at least $104. If everyone else has the same preferences that you do, then the interest rate in the economy as a whole will be 4 percent.

What if everyone does not have the same preferences that you do? Suppose that others will lend only when they get back 5 percent more at the end of the year? In that case, the interest rate in the economy as a whole will be 5 percent, simply because businesses and government cannot borrow the money they want for any less and they do not have to offer any more. Faced with a national interest rate of 5 percent, you would have no reason to accept less, even though you would take 4 percent if you had to.

In this situation, let us return to the question of how much you would be willing to bid for a $10,000 bond that matures a year from now. With an interest rate of 5 percent being available in the economy as a whole, it would not pay you to bid more than $9,523.81 for a $10,000 bond that matures a year from now. By investing that same amount of money somewhere else today at 5 percent, you could get back $10,000 in a year. Therefore, there is no reason for you to bid more than $9,523.81 for the $10,000 bond.

What if the interest rate in the economy as a whole had been 12 percent, rather than 5 percent? Then it would not pay you to bid more than $8,928.57 for a $10,000 bond that matures a year from now. In short, what people will bid for bonds depends on how much they could get for the same money by putting it somewhere else. That is why bond prices go down when the interest rate goes up, and vice versa.

What this also says is that, when the interest rate is 5 percent, $9,523.81 in the year 2014 is the same as $10,000 in the year 2015. This raises questions about the taxation of capital gains. If someone buys a bond for the former price and sells it a year later for the latter price, the government will of course want to tax the $476.19 difference. But is that really the same as an increase in value, if the two sums of money are just equivalent to one another? What if there has been a one percent inflation, so that the $10,000 received back would not have been enough to compensate for waiting, if the investor had expected inflation to reduce the real value of the bond? What if there had been a 5 percent inflation, so that the amount received back was worth no more than the amount originally lent, with no reward at all for waiting for the postponed repayment? Clearly, the investor would be worse off than if he or she had never bought the bond. How then can this “capital gain” really be said to be a gain?

These are just some of the considerations that make the taxation of capital gains more complicated than the taxation of such other forms of income as wages and salaries. Some governments in some countries do not tax capital gains at all, while the rate at which such gains are taxed in the United States remains a matter of political controversy.

Landsburg expands on this point:

Michael Kinsley, a journalist I much admire (and who hired me years ago to write for Slate magazine, for which I will be forever grateful), has a very persistent bee in his bonnet about capital gains, which he believes should be taxed at the same rate as wage income. The Kinsley argument, which he has repeated in countless (well, I at least have lost count) magazine and newspaper columns, runs like this:

(a) Economic theory tells us that everything should be taxed at the same rate.

(b) Q.E.D.

Step (a) is correct. Economic theory does tell us that we generally get better outcomes when everything is taxed at the same rate. If apples were taxed at 10 percent and oranges at 30 percent, some orange lovers would switch to eating apples just to save a buck. Better to tax both at 20 percent and encourage people to eat the fruits they prefer.

It’s in the transition from step (a) to step (b) that Kinsley loses his intellectual footing. He goes wrong because he misinterprets the word “everything.” The argument applies to apples and oranges, it applies to Coke and Pepsi, and it applies to red sneakers and blue sneakers. It also applies to apples consumed today and apples consumed tomorrow. If apples are taxed at 10 percent today and 30 percent tomorrow, some people will eat more apples today and fewer tomorrow just to save a buck. Better to tax all apples at 20 percent and encourage people to time their meals as they prefer.

But unlike apples and oranges or red sneakers and blue sneakers, “wage income” and “capital gains income” are not consumption goods that people choose between. Therefore the argument doesn’t apply to them.

But it’s worse than that. It turns out that if you take the Kinsley principle seriously—if, that is, you are determined to tax both current and future apples at the same rate—then you must be committed to taxing all capital income (including interest, dividends, and capital gains) at a rate of zero.

To understand why, it helps to have an imaginary friend.

My imaginary friend Alice earns $1 a day. Alice can use that dollar either to buy an apple or to invest in an interest-bearing account, wait for it to double, and then buy two apples.

If we tax Alice’s wages at, say, 50 percent, then her take-home pay falls to 50 cents a day. She can use that 50 cents either to buy half an apple or to invest in an interest-bearing account, wait for it to double, and then buy one apple. Either way, her buying power is cut in half. Instead of taxing her wages, we might as well have imposed a sales tax that doubles the price of apples, both now and in the future.

In other words, taxing Alice’s wages is just like taxing both her current and future apple purchases—and taxing both at the same rate.

Now along comes Michael Kinsley to complain that Alice pays no tax on her interest earnings. We therefore amend the tax code to include a 50 percent tax on interest.

Alice still pays the wage tax, so her take-home pay is still 50 cents a day. She can use that 50 cents either to buy half an apple or to invest in an interest-bearing account, wait for it to double, pay 25 cents tax on the interest she’s earned, and use the remaining 75 cents to buy three-fourths of an apple.

Under the Kinsley tax plan (including both the wage tax and the capital gains tax), Alice’s purchasing power today is cut by half (from one apple to half an apple), but her purchasing power tomorrow is cut by by more than half (from two apples to three-fourths of an apple). It’s exactly as if we’d imposed a sales tax on today’s apples and a higher sales tax on tomorrow’s apples.

In other words, taxing both wages and interest is just like taxing current apple purchases at one rate and future apple purchases at another.

In still other words, the Kinsley Tax Plan stands in direct contradiction to the Kinsley Prescription to tax everything equally. By taxing future apples at a higher rate than current apples, the Tax Plan encourages Alice to eat more apples now and fewer later, even when she’d prefer to space out her consumption more evenly.

If it took you a little while to digest that example, don’t feel bad; it took the economics profession a long time to digest it too. (And on a personal note, I remember absolutely disbelieving this argument when I first heard about it, and needing it explained to me multiple times before I got it—though my hope is that I’m explaining it to you more clearly than it was explained to me.) The details of the argument were worked out in the 1980s by Christophe Chamley (then at Harvard) and Ken Judd (at Stanford); the Chamley-Judd result is now considered a central pillar of the theory of public finance.

So the argument that Michael Kinsley offers in favor of a higher tax on capital gains is in fact, when properly understood, an argument in favor of a zero tax not just on capital gains but on dividends and interest as well.

That’s not a proof that we should never tax capital income; it’s one argument against taxing capital income, which might or might not be trumped by other arguments in the opposite direction. But surely there’s no point in making arguments in the first place if we don’t take the trouble to understand them.

I agree with Landsburg’s last comment there that this isn’t necessarily a categorical argument that capital gains should never be taxed; we can certainly come up with counterarguments that may or may not outweigh it. But it does provide yet another illustration of why messing with market prices can be such a tricky prospect, and how it can lead to unintended negative side effects. To be sure, there’s a reason why this idea keeps coming up throughout this post; messing with prices almost always has secondary effects. And for still more examples of this, we need only examine all the other various kinds of interventions that are even more direct than capital gains taxes, which attempt to limit the amount of interest lenders can collect from borrowers via mechanisms like interest rate ceilings and other such restrictions. As Sowell writes:

Misconceptions about money-lending often take the form of laws attempting to help borrowers by giving them more leeway in repaying loans. But anything that makes it difficult to collect a debt when it is due makes it less likely that loans will be made in the first place, or will be made at the lower interest rates that would prevail in the absence of such debtor-protection policies by governments.

In some societies, people are not expected to charge interest on loans to relatives or fellow members of the local community, nor to be insistent on prompt payment according to the letter of the loan agreement. These kinds of preconditions discourage loans from being made in the first place, and sometimes they discourage individuals from letting it be known that they have enough money to be able to lend. In societies where such social pressures are particularly strong, incentives for acquiring wealth are reduced. This is not only a loss to the individual who might otherwise have made wealth by going all out, it is a loss to the whole society when people who are capable of producing things that many others are willing to pay for may not choose to go all out in doing so.

We also have to be wary of secondary effects when it comes to things like short-term “payday loans,” which are often regarded as being highly exploitative, but which usually have valid reasons for charging the high interest rates that they do. Sowell continues:

Not everything that is called interest is in fact interest. […] When loans are made, for example, what is charged as interest includes not only the rate of return necessary to compensate for the time delay in receiving the money back, but also an additional amount to compensate for the risk that the loan will not be repaid, or repaid on time, or repaid in full. What is called interest also includes the costs of processing the loan. With small loans, especially, these process costs can become a significant part of what is charged because process costs do not vary as much as the amount of the loan varies. That is, lending a thousand dollars does not require ten times as much paperwork as lending a hundred dollars.

In other words, process costs on small loans can be a larger share of what is loosely called interest. Many of the criticisms of small financial institutions that operate in low-income neighborhoods grow out of misconstruing various charges that are called interest but are not, in the strict sense in which economists use the term for payments received for time delay in receiving repayment and the risk that the repayment will not be made in full or on time, or perhaps at all.

Short-term loans to low-income people are often called “payday loans,” since they are to be repaid on the borrower’s next payday or when a Social Security check or welfare check arrives, which may be only a matter of weeks, or even days, away. Such loans, according to the Wall Street Journal, are “usually between $300 and $400.” Obviously, such loans are more likely to be made to people whose incomes and assets are so low that they need a modest sum of money immediately for some exigency and simply do not have it.

The media and politicians make much of the fact that the annual rate of interest (as they loosely use the term “interest”) on these loans is astronomical. The New York Times, for example referred to “an annualized interest rate of 312 percent” on some such loans. But payday loans are not made for a year, so the annual rate of interest is irrelevant, except for creating a sensation in the media or in politics. As one owner of a payday loan business pointed out, discussing annual interest rates on payday loans is like saying salmon costs more than $15,000 a ton or a hotel room rents for more than $36,000 a year, since most people never buy a ton of salmon or rent a hotel room for a year.

Whatever the costs of processing payday loans, those costs as well as the cost of risk must be recovered from the interest charged—and the shorter the period of time involved, the higher the annual interest rate must be to cover those fixed costs. For a two-week loan, payday lenders typically charge $15 in interest for every $100 lent. When laws restrict the annual interest rate to 36 percent, this means that the interest charged for a two-week loan would be less than $1.50—an amount unlikely to cover even the cost of processing the loan, much less the risk involved. When Oregon passed a law capping the annual interest rate at 36 percent, three-quarters of the hundreds of payday lenders in the state closed down. Similar laws in other states have also shut down many payday lenders.

So-called “consumer advocates” may celebrate such laws but the low-income borrower who cannot get the $100 urgently needed may have to pay more than $15 in late fees on a credit card bill or pay in other consequences—such as having a car repossessed or having the electricity cut off—that the borrower obviously considered more detrimental than paying $15, or the transaction would not have been made in the first place.

The lower the interest rate ceiling, the more reliable the borrowers would have to be, in order to make it pay to lend to them. At a sufficiently low interest rate ceiling, it would pay to lend only to millionaires and, at a still lower interest rate ceiling, it would pay to lend only to billionaires.

In short, for all the flak that payday lenders get for being “greedy” and “exploitative,” the high interest rates they charge are little more than a product of market conditions. As unfortunate as it is that so many low-income borrowers have no better options available to them, the fact is that without these payday lenders, a lot of them would ultimately be worse off.

Speaking of lenders who are even more reviled than normal bankers, though, let’s close out this topic with a discussion of the least popular financiers of all: Wall Street speculators. This might be the one group that’s widely considered even more shamelessly greedy than payday lenders – and their reputation (quite fairly) suffered even more after the 2008 financial crash. But as Sowell points out, even these speculators serve a legitimate financial function, and a lot of people would be worse off without them:

Most market transactions involve buying things that exist, based on whatever value they have to the buyer and whatever price is charged by the seller. Some transactions, however, involve buying things that do not yet exist or whose value has yet to be determined—or both. For example, the price of stock in the Internet company Amazon.com rose for years before the company made its first dollar of profits. People were obviously speculating that the company would eventually make profits or that others would keep bidding up the price of its stock, so that the initial stockholder could sell the stock for a profit, whether or not Amazon.com itself ever made a profit. Amazon.com was founded in 1994. After years of operating at a loss, it finally made its first profit in 2001.

Exploring for oil is another costly speculation, since millions of dollars may be spent before discovering whether there is in fact any oil at all where the exploration is taking place, much less whether there is enough oil to repay the money spent.

Many other things are bought in hopes of future earnings which may or may not materialize—scripts for movies that may never be made, pictures painted by artists who may or may not become famous some day, and foreign currencies that may go up in value over time, but which could just as easily go down. Speculation as an economic activity may be engaged in by people in all walks of life but there are also professional speculators for whom this is their whole career.

One of the professional speculator’s main roles is in relieving other people from having to speculate as part of their regular economic activity, such as farming for example, where both the weather during the growing season and the prices at harvest time are unpredictable. Put differently, risk is inherent in all aspects of human life. Speculation is one way of having some people specialize in bearing these risks, for a price. For such transactions to take place, the cost of the risk being transferred from whoever initially bears that risk must be greater than what is charged by whoever agrees to take on the risk. At the same time, the cost to whoever takes on that risk must be less than the price charged.

In other words, the risk must be reduced by this transfer, in order for the transfer to make sense to both parties. The reason for the speculator’s lower cost may be more sophisticated methods of assessing risk, a larger amount of capital available to ride out short-run losses, or because the number and variety of the speculator’s risks lowers his overall risk. No speculator can expect to avoid losses on particular speculations but, so long as the gains exceed the losses over time, speculation can be a viable business.

The other party to the transaction must also benefit from the net reduction of risk. When an American wheat farmer in Idaho or Nebraska is getting ready to plant his crop, he has no way of knowing what the price of wheat will be when the crop is harvested. That depends on innumerable other wheat farmers, not only in the United States but as far away as Russia or Argentina.

If the wheat crop fails in Russia or Argentina, the world price of wheat will shoot up, because of supply and demand, causing American wheat farmers to get very high prices for their crop. But if there are bumper crops of wheat in Russia and Argentina, there may be more wheat on the world market than anybody can use, with the excess having to go into expensive storage facilities. That will cause the world price of wheat to plummet, so that the American farmer may have little to show for all his work, and may be lucky to avoid taking a loss on the year. Meanwhile, he and his family will have to live on their savings or borrow from whatever sources will lend to them.

In order to avoid having to speculate like this, the farmer may in effect pay a professional speculator to carry the risk, while the farmer sticks to farming. The speculator signs contracts to buy or sell at prices fixed in advance for goods to be delivered at some future date. This shifts the risk of the activity from the person engaging in it—such as the wheat farmer, in this case—to someone who is, in effect, betting that he can guess the future prices better than the other person and has the financial resources to ride out the inevitable wrong bets, in order to make a net profit over all because of the bets that turn out better.

Speculation is often misunderstood as being the same as gambling, when in fact it is the opposite of gambling. What gambling involves, whether in games of chance or in actions like playing Russian roulette, is creating a risk that would otherwise not exist, in order either to profit or to exhibit one’s skill or lack of fear. What economic speculation involves is coping with an inherent risk in such a way as to minimize it and to leave it to be borne by whoever is best equipped to bear it.

When a commodity speculator offers to buy wheat that has not yet been planted, that makes it easier for a farmer to plant wheat, without having to wonder what the market price will be like later, at harvest time. A futures contract guarantees the seller a specified price in advance, regardless of what the market price may turn out to be at the time of delivery. This separates farming from economic speculation, allowing each to be done by different people, who specialize in different economic activities. The speculator uses his knowledge of the market, and of economic and statistical analysis, to try to arrive at a better guess than the farmer may be able to make, and thus is able to offer a price that the farmer will consider an attractive alternative to waiting to sell at whatever price happens to prevail in the market at harvest time.

Although speculators seldom make a profit on every transaction, they must come out ahead in the long run, in order to stay in business. Their profit depends on paying the farmer a price that is lower on average than the price which actually emerges at harvest time. The farmer also knows this, of course. In effect, the farmer is paying the speculator for carrying the risk, just as one pays an insurance company. As with other goods and services, the question may be raised as to whether the service rendered is worth the price charged. At the individual level, each farmer can decide for himself whether the deal is worth it. Each speculator must of course bid against other speculators, as each farmer must compete with other farmers, whether in making futures contracts or in selling at harvest time.

From the standpoint of the economy as a whole, competition determines what the price will be and therefore what the speculator’s profit will be. If that profit exceeds what it takes to entice investors to risk their money in this volatile field, more investments will flow into this segment of the market until competition drives profits down to a level that just compensates the expenses, efforts, and risks.

Competition is visibly frantic among speculators who shout out their offers and bids in commodity exchanges. Prices fluctuate from moment to moment and a five-minute delay in making a deal can mean the difference between profits and losses. Even a modest-sized firm engaging in commodity speculation can gain or lose hundreds of thousands of dollars in a single day, and huge corporations can gain or lose millions in a few hours.

Commodity markets are not just for big businesses or even for farmers in technologically advanced countries. A New York Times dispatch from India reported:

At least once a day in this village of 2,500 people, Ravi Sham Choudhry turns on the computer in his front room and logs in to the Web site of the Chicago Board of Trade.

He has the dirt of a farmer under his fingernails and pecks slowly at the keys. But he knows what he wants: the prices for soybean commodity futures.

This was not an isolated case. As of 2003, there were 3,000 organizations in India putting as many as 1.8 million Indian farmers in touch with the world’s commodity markets. The farmer just mentioned served as an agent for fellow farmers in surrounding villages. As one sign of how fast such Internet commodity information is spreading, Mr. Choudhry earned $300 the previous year from this activity that is incidental to his farming, but now earned that much in one month. That is a very significant sum in a poor country like India.

Agricultural commodities are not the only ones in which commodity traders speculate. One of the most dramatic examples of what can happen with commodity speculation involved the rise and fall of silver prices in 1980. Silver was selling at $6.00 an ounce in early 1979 but skyrocketed to a high of $50.05 an ounce by early 1980. However, this price began a decline that reached $21.62 on March 26th. Then, in just one day, that price was cut by more than half to $10.80. In the process, the billionaire Hunt brothers, who were speculating heavily in silver, lost more than a billion dollars within a few weeks. Speculation is one of the financially riskiest activities for the individual speculator, though it reduces risks for the economy as a whole.

Speculation may be engaged in by people who are not normally thought of as speculators. As far back as the 1870s, a food-processing company headed by Henry Heinz signed contracts to buy cucumbers from farmers at pre-arranged prices, regardless of what the market prices might be when the cucumbers were harvested. Then as now, those farmers who did not sign futures contracts with anyone were necessarily engaging in speculation about prices at harvest time, whether or not they thought of themselves as speculators. Incidentally, the deal proved to be disastrous for Heinz when there was a bumper crop of cucumbers, well beyond what he expected or could afford to buy, forcing him into bankruptcy. It took him years to recover financially and start over, eventually founding the H.J. Heinz company that continues to exist today.

Because risk is the whole reason for speculation in the first place, being wrong is a common experience, though being wrong too often means facing financial extinction. Predictions, even by very knowledgeable people, can be wrong by vast amounts. The distinguished British magazine The Economist predicted in March 1999 that the price of a barrel of oil was heading down, when in fact it headed up—and by December oil was selling for five times the price suggested by The Economist. In the United States, predictions about inflation by the Federal Reserve System have more than once turned out to be wrong, and the Congressional Budget Office has likewise predicted that a new tax law would bring in more tax revenue, when in fact tax revenues fell instead of rising, and in other cases the CBO predicted falling revenues from a new tax law, when in fact revenues rose.

Futures contracts are made for delivery of gold, oil, soybeans, foreign currencies and many other things at some price fixed in advance for delivery on a future date. Commodity speculation is only one kind of speculation. People also speculate in real estate, corporate stocks, or other things.

The full cost of risk is not only the amount of money involved, it is also the worry that hangs over the individual while waiting to see what happens. A farmer may expect to get $1,000 a ton for his crop but also knows that it could turn out to be $500 a ton or $1,500. If a speculator offers to guarantee to buy his crop at $900 a ton, that price may look good if it spares the farmer months of sleepless nights wondering how he is going to support his family if the harvest price leaves him too little to cover his costs of growing the crop.

Not only may the speculator be better equipped financially to deal with being wrong, he may be better equipped psychologically, since the kind of people who worry a lot do not usually go into commodity speculation. A commodity speculator I knew had one year when his business was operating at a loss going into December, but things changed so much in December that he still ended up with a profit for the year—to his surprise, as much as anyone else’s. This is not an occupation for the faint of heart.

Economic speculation is another way of allocating scarce resources—in this case, knowledge. Neither the speculator nor the farmer knows what the prices will be when the crop is harvested. But the speculator happens to have more knowledge of markets and of economic and statistical analysis than the farmer, just as the farmer has more knowledge of how to grow the crop. My commodity speculator friend admitted that he had never actually seen a soybean and had no idea what they looked like, even though he had probably bought and sold millions of dollars’ worth of soybeans over the years. He simply transferred ownership of his soybeans on paper to soybean buyers at harvest time, without ever taking physical possession of them from the farmer. He was not really in the soybean business, he was in the risk management business.

Sowell concludes:

Economic activities for dealing with inescapable risks seek both to minimize these risks and shift them to those best able to carry them. Those who accept these risks typically have not only the financial resources to ride out short-run losses but also have lower risks from a given situation than the person who transferred the risk. A commodity speculator can reduce risks overall by engaging in a wider variety of risky activities than a farmer does, for example.

While a wheat farmer can be wiped out if bumper crops of wheat around the world force the price far below what was expected when the crop was planted, a similar disaster would be unlikely to strike wheat, gold, cattle, and foreign currencies simultaneously, so that a professional speculator who speculated in all these things would be in less danger than someone who speculated in any one of them, as a wheat farmer does.

Whatever statistical or other expertise the speculator has further reduces the risks below what they would be for the farmer or other producer. More fundamentally, from the standpoint of the efficient use of scarce resources, speculation reduces the costs associated with risks for the economy as a whole. One of the important consequences, in addition to more people being able to sleep well at night because of having a guaranteed market for their output, is that more people find it worthwhile to produce things under risky conditions than would have otherwise. In other words, the economy can produce more soybeans because of soybean speculators, even if the speculators themselves know nothing about growing soybeans.

It is especially important to understand the interlocking mutual interests of different economic groups—the farmer and the speculator being just one example—and, above all, the effects on the economy as a whole, because these are things often neglected or distorted in the zest of the media for emphasizing conflicts, which is what sells newspapers and gets larger audiences for television news programs. Politicians likewise benefit from portraying different groups as enemies of one another and themselves as the saviors of the group they claim to represent.

When wheat prices soar, for example, nothing is easier for a demagogue than to cry out against the injustice of a situation where speculators, sitting comfortably in their air-conditioned offices, grow rich on the sweat of farmers toiling in the fields for months under a hot sun. The years when the speculators took a financial beating at harvest time, while the farmers lived comfortably on the guaranteed wheat prices paid by speculators, are of course forgotten.

Similarly, when an impending or expected shortage drives up prices, much indignation is often expressed in politics and the media about the higher retail prices being charged for things that the sellers bought from their suppliers when prices were lower. What things cost under earlier conditions is history; what the supply and demand are today is economics.

During the early stages of the 1991 Persian Gulf War, for example, oil prices rose sharply around the world, in anticipation of a disruption of Middle East oil exports because of impending military action in the region. At this point, a speculator rented an oil tanker and filled it with oil purchased in Venezuela to be shipped to the United States. However, before the tanker arrived at an American port, the Gulf War of 1991 was over sooner than anyone expected and oil prices fell, leaving the speculator unable to sell his oil for enough to recover his costs. Here too, what he paid in the past was history and what he could get now was economics.

From the standpoint of the economy as a whole, different batches of oil purchased at different times, under different sets of expectations, are the same when they enter the market today. There is no reason why they should be priced differently, if the goal is to allocate scarce resources in the most efficient way.

In chaotic times, it can be tempting to blame the market for everything that’s going wrong, and to want to overrule the market mechanism with more direct forms of control, like bans and regulations and price controls and so on. Likewise, when it becomes apparent that some people are making tons of money while others lose out, it can be tempting to want to smooth out these disparities by clamping down on how freely the market can operate. Ultimately, though, these kinds of interventions almost always have side effects – and they’re not always worth it. Taking away the market’s ability to operate freely – as tempting as it might be when it comes to things like Wall Street speculation, with all of its crazy profits and losses – can often leave regular people (like famers, homeowners, and other ordinary borrowers) worse off. True, letting the market do its thing often means that some people will hit it big while others will incur major losses; but the end result is more often than not better for society as a whole than the alternative. That isn’t to say that after-the-fact adjustments and redistributions can’t be made where appropriate, of course, in order to ensure that nobody completely falls through the cracks; such measures can and absolutely should be taken. It’s simply to reaffirm what we’ve been saying throughout this post, that taking these measures after the market has set price levels tends to have better outcomes than trying to interfere with the market directly with price controls and overly restrictive bans and so on.