I – II – III – IV – V – VI – VII – VIII – IX – X – XI – XII – XIII – XIV – XV – XVI – XVII – XVIII – XIX – XX – XXI – XXII – XXIII – XXIV – XXV – XXVI – XXVII – XXVIII – XXIX

[Single-page view]

We talked earlier about how competition forces most companies to price their products at a level that just barely covers their costs of production, but also noted that in the case of monopolies, the absence of such competition allows them to get away with charging more, thereby keeping more of what might otherwise be consumer surplus for themselves as profits. With labor, it’s largely the same story. If there are a lot of people who are willing and able to do a particular job – i.e. if the labor supply is high – then the high level of competition for that job will ensure that none of them will be able to ask for an exorbitantly high wage for doing it – because if they did, the employer would be able to simply turn them down and hire someone else instead who wasn’t asking for quite as much. On the other hand though, if hardly anyone is willing or able to do a particular job – i.e. if the labor supply is low – then the situation is reversed; employers will have to offer a higher wage just to induce workers to come work for them in the first place. This might be the case in a situation where, for instance, the job requires an extremely rare set of qualifications that only a few workers have – as with professional athletes, whose skills are so rare that they’re able to command multi-million-dollar salaries from the teams competing for their services. Or alternatively, it might be a case of the job simply being so unpleasant or dangerous or difficult that only a few workers are willing to tolerate it – as with Alaskan crab fishermen, who can earn the seasonal equivalent of six-figure salaries for their unglamorous work despite it not requiring much in terms of education or advanced training. In the latter case, wage rates will have to adjust until these jobs with less inherent appeal but higher pay are about as enticing to workers as the more normal jobs that offer more inherent appeal but (because they’re more tolerable) can get away with offering lower pay. As Robert H. Frank writes:

In product markets, the price of a good depends on its attributes. A high-definition TV, for example, commands a higher price than a conventional one. The same is true in labor markets, where the wage associated with a given job will depend on its characteristics. What economists call the theory of compensating wage differentials was originally advanced by Adam Smith in The Wealth of Nations:

The whole of the advantages and disadvantages of the different employments of labour and stock, must, in the same neighbourhood, be either perfectly equal, or continually tending to equality. If, in the same neighbourhood, there was any employment evidently either more or less advantageous than the rest, so many people would crowd into it in the one case, and so many would desert it in the other, that its advantages would soon return to the level of other employments. . . . Every man’s interest would prompt him to seek the advantageous, and to shun the disadvantageous employment.

Smith’s theory thus explains why, when all other relevant factors are the same, wages will be higher in jobs that are more risky, require more arduous effort, or are located in ugly or smelly locations.

And it’s this organic process of wage adjustment that ultimately allows for every kind of company to fulfill its need for employees – even the kinds of companies that you might imagine would have a harder time attracting employees in a vacuum. Again, there’s no central planning involved; as Heath explains, the incentives just naturally direct workers to where their services are needed (he calls this a kind of coercion, which might be a looser use of the term than some pro-market readers would like, but you can get what he means):

It is important to remember that the assignment of individuals to jobs in a market economy is unplanned. In order for our society to run smoothly, a certain number of people have to agree to become doctors, pilots, primary-school teachers, chefs, mechanics, garbage collectors, computer programmers, and so on. Yet if you took a poll of high school students and asked them what they wanted to be when they grew up, you’d find that people don’t just spontaneously divide up into the relevant occupational groups. (And needless to say, an economy in which half of the people are rappers, actresses, or art-house filmmakers would not work very well.) So you need to have some mechanism that channels people into the occupations where they are needed and diverts them from the occupations that are overcrowded. This process is necessarily coercive, since it requires most people to give up on what they themselves would like to be doing (artist, actor, musician), in order to do something that “society” requires (waiter, data-entry clerk, administrative assistant, salesperson).

This coercion can be achieved in various ways. One can imagine a planned economy, where students all take an aptitude test upon graduation and are then assigned to a job by some giant computer that keeps track of who’s doing what. Obviously, this is unattractive. The alternative solution, in a market economy, is simply to have a competitive labor market. When all goes smoothly, this will ensure that wages in overcrowded sectors will be bid down, while wages in undersupplied sectors will rise. As a result, people will shuffle around until all the jobs are filled, attracted by the high wages available in some sectors, repelled by the low wages and unemployment in others. The fact that people are choosing to do so should not obscure the fact that the labor market is still, at some level, serving a coercive role—pushing people to give up on their dreams and to accept a more pedestrian life than they might have hoped for. And the way this is achieved is through changes in the wages that are paid, along with the unemployment rates that prevail within the relevant sectors. (Think of how much effort society must expend on this front in order to discourage too many people from becoming actors.) It is important, then, when thinking about how “fair” or “unfair” a particular wage is, to keep in mind that we rely upon the labor market to impose a lot of hard decisions upon people. The mere fact that it is impossible to earn a living wage in a particular occupation does not mean that there is any unfairness in the fact that people are paid that wage. It may mean that “society” does not require any more people to enter that occupation: Too many people are doing it already.

Heath is right to point out that this question of “fair” vs. “unfair” wages can be a tricky one. In terms of pure justice and fairness, it seems like the ideal rule (at least in theory) would be to just have everyone get paid the same regardless of their job; after all, as I discussed in my last post, it’s not like anyone can really claim direct credit for whatever innate traits or talents they might have that would make them more successful in some jobs and less successful in others – so in the ultimate sense, no one can really be said to “deserve” any more or less than anyone else. The thing is, though, when an employer pays a worker, it’s not really a question of desert. That is, it’s not like donating to a charity; the money isn’t being handed over just because the giver thinks the recipient is an especially worthy person who deserves it or needs it more than anyone else. (If they were thinking along these lines, they probably would just be donating to charity instead.) Rather, the employer is paying the worker specifically because they have a particular task they need done, and they know the pay will induce the worker to do that task for them. In other words, as Sowell succinctly puts it:

Pay is not a retrospective reward for merit but a prospective incentive for contributing to production.

And when we consider things in light of this key insight, we can see that even in the most progressive-minded of market economies, some degree of pay inequality will always be unavoidable, due to the simple fact that some jobs will always require more of a financial incentive to do than others. As Friedman and Friedman write:

However we might wish it otherwise, it simply is not possible to use prices to transmit information and provide an incentive to act on that information without using prices also to affect, even if not completely determine, the distribution of income. If what a person gets does not depend on the price he receives for the services of his resources, what incentive does he have to seek out information on prices or to act on the basis of that information? If Red Adair’s income would be the same whether or not he performs the dangerous task of capping a runaway oil well, why should he undertake the dangerous task? He might do so once, for the excitement. But would he make it his major activity? If your income will be the same whether you work hard or not, why should you work hard? Why should you make the effort to search out the buyer who values most highly what you have to sell if you will not get any benefit from doing so? If there is no reward for accumulating capital, why should anyone postpone to a later date what he could enjoy now? Why save? How would the existing physical capital ever have been built up by the voluntary restraint of individuals? If there is no reward for maintaining capital, why should people not dissipate any capital which they have either accumulated or inherited? If prices are prevented from affecting the distribution of income, they cannot be used for other purposes. The only alternative is command. Some authority would have to decide who should produce what and how much. Some authority would have to decide who should sweep the streets and who manage the factory, who should be the policeman and who the physician.

Needless to say, then, they consider the market approach to be the better option, even if it does lead to some inequality of income. Friedman elaborates further on this point:

The ethical principle that would directly justify the distribution of income in a free market society is, “To each according to what he and the instruments he owns produces.”

[…]

What is the relation between this principle and another that seems ethically appealing, namely, equality of treatment? In part, the two principles are not contradictory. Payment in accordance with product may be necessary to achieve true equality of treatment. Given individuals whom we are prepared to regard as alike in ability and initial resources, if some have a greater taste for leisure and others for marketable goods, inequality of return through the market is necessary to achieve equality of total return or equality of treatment. One man may prefer a routine job with much time off for basking in the sun to a more exacting job paying a higher salary; another man may prefer the opposite. If both were paid equally in money, their incomes in a more fundamental sense would be unequal. Similarly, equal treatment requires that an individual be paid more for a dirty, unattractive job than for a pleasant rewarding one. Much observed inequality is of this kind. Differences of money income offset differences in other characteristics of the occupation or trade. In the jargon of economists, they are “equalizing differences” required to make the whole of the “net advantages,” pecuniary and non-pecuniary, the same.

Another kind of inequality arising through the operation of the market is also required, in a somewhat more subtle sense, to produce equality of treatment, or to put it differently to satisfy men’s tastes. It can be illustrated most simply by a lottery. Consider a group of individuals who initially have equal endowments and who all agree voluntarily to enter a lottery with very unequal prizes. The resultant inequality of income is surely required to permit the individuals in question to make the most of their initial equality. Redistribution of the income after the event is equivalent to denying them the opportunity to enter the lottery. This case is far more important in practice than would appear by taking the notion of a “lottery” literally. Individuals choose occupations, investments, and the like partly in accordance with their taste for uncertainty. The girl who tries to become a movie actress rather than a civil servant is deliberately choosing to enter a lottery, so is the individual who invests in penny uranium stocks rather than government bonds. Insurance is a way of expressing a taste for certainty. Even these examples do not indicate fully the extent to which actual inequality may be the result of arrangements designed to satisfy men’s tastes. The very arrangements for paying and hiring people are affected by such preferences. If all potential movie actresses had a great dislike of uncertainty, there would tend to develop “cooperatives” of movie actresses, the members of which agreed in advance to share income receipts more or less evenly, thereby in effect providing themselves insurance through the pooling of risks. If such a preference were widespread, large diversified corporations combining risky and non-risky ventures would become the rule. The wild-cat oil prospector, the private proprietorship, the small partnership, would all become rare.

Of course, people’s differing levels of tolerance for hardship and risk are just one reason why their incomes might be unequal, so this obviously isn’t the full story. There are plenty of people out there who make very high incomes despite their jobs being perfectly safe and cushy. There are plenty of people who earn generous salaries despite, frankly, not having to work very hard or risk very much at all. So then why isn’t it the case that the people who work hardest and take the most difficult jobs automatically make the most money? Shouldn’t we want the hardest workers to earn the greatest rewards? Well, again, it’s not quite so simple. Hard work and effort alone, while obviously important, aren’t the be-all-end-all – and in fact, upon reflection, most people wouldn’t actually want them to be, as Michael Sandel points out:

Although proponents of meritocracy often invoke the virtues of effort, they don’t really believe that effort alone should be the basis of income and wealth. Consider two construction workers.

One is strong and brawny, and can build four walls in a day without breaking a sweat. The other is weak and scrawny, and can’t carry more than two bricks at a time. Although he works very hard, it takes him a week to do what his muscular co-worker achieves, more or less effortlessly, in a day. No defender of meritocracy would say the weak but hardworking worker deserves to be paid more, in virtue of his superior effort, than the strong one.

Or consider Michael Jordan. It’s true, he practiced hard. But some lesser basketball players practice even harder. No one would say they deserve a bigger contract than Jordan’s as a reward for all the hours they put in. So, despite the talk about effort, it’s really contribution, or achievement, that the meritocrat believes is worthy of reward.

Again, pay is an incentive for production, not a reward for merit. As much as we’ve talked about the importance of labor supply and how it can affect the wage rate for a particular job, an equally important counterbalancing force is the demand for that labor – i.e. how much people are actually willing to pay for it. You might be willing to work harder than anyone in the world at a particular job, but if the product of your work isn’t something that people actually want (like for instance, if you’re an artist or architect creating designs that nobody else actually likes), then you can’t expect to be handsomely rewarded for your efforts solely on the basis of how hard you worked on them. You have to actually be producing something of value for buyers. The more value you can create for them, the more they’ll be willing to pay you for it – and conversely, the less value you create for them, the less they’ll be willing to pay for it. Here’s Sowell again:

How much people are paid depends on many things. Stories about the astronomical pay of professional athletes, movie stars, or chief executives of big corporations often cause journalists and others to question how much this or that person is “really” worth.

Fortunately, since we know […] that there is no such thing as “real” worth, we can save all the time and energy that others put into such unanswerable questions. Instead, we can ask a more down-to-earth question: What determines how much people get paid for their work? To this question there is a very down-to-earth answer: Supply and Demand. However, that is just the beginning. Why does supply and demand cause one individual to earn more than another?

Workers would obviously like to get the highest pay possible and employers would like to pay the least possible. Only where there is overlap between what is offered and what is acceptable can anyone be hired. But why does that overlap take place at a pay rate that is several times as high for an engineer as for a messenger?

Messengers would of course like to be paid what engineers are paid, but there is too large a supply of people capable of being messengers to force employers to raise their pay scales to that level. Because it takes a long time to train an engineer, and not everyone is capable of mastering such training, there is no such abundance of engineers relative to the demand. That is the supply side of the story. But what determines the demand for labor? What determines the limit of what an employer is willing to pay?

It is not merely the fact that engineers are scarce that makes them valuable. It is what engineers can add to a company’s earnings that makes employers willing to bid for their services—and sets a limit to how high the bids can go. An engineer who added $100,000 to a company’s earnings and asked for a $200,000 salary would obviously not be hired. On the other hand, if the engineer added a quarter of a million dollars to a company’s earnings, that engineer would be worth hiring at $200,000—provided that there were no other engineers who would do the same job for a lower salary.

So to return to our original question: How high a wage can a worker expect to earn for a particular job in a free market? The answer is “somewhere between the minimum amount that would make that job preferable to whatever other alternatives are available to the worker, and the full amount of value that the work creates for the employer.” Where exactly the wage ultimately falls on this spectrum, naturally, depends on how tight the labor market is for the job in question; if there are a ton of other workers competing for the position, the pay will tend to be on the lower end, but if practically no one else is willing and able to do the job, the pay will tend to be toward the higher end. Either way, though, it will always fall somewhere between these two constraints; if it were any lower, the worker wouldn’t take the job in the first place, and if it were any higher, the employer wouldn’t hire them in the first place. Commenter Scott-H-Young gives the big-picture summary:

[As a worker,] you have a minimum amount of money, that, if you earned below this, you’d just choose not to have a job at all. Imagine if you were unemployed and I offered you ten cents an hour to pick dandelions for me. You’d probably tell me to go to hell—being unemployed is better than this job.

Companies, similarly, have a maximum amount of money, that, if they pay higher than this, the cost of paying you isn’t worth the value you bring. This is the “extra” value you bring to the company, not the amount of profit the company makes divided by total employees. The question to the company is, if I have someone employed in this position for $X, will I earn more than $X in extra profit. If they don’t, then the job is effectively charity because the company loses money by hiring you.

These two prices establish upper and lower bounds. Maybe $4/hour is the minimum amount which is better than being unemployed for you. Maybe $15/hour is the maximum amount a company can afford to pay you without losing money.

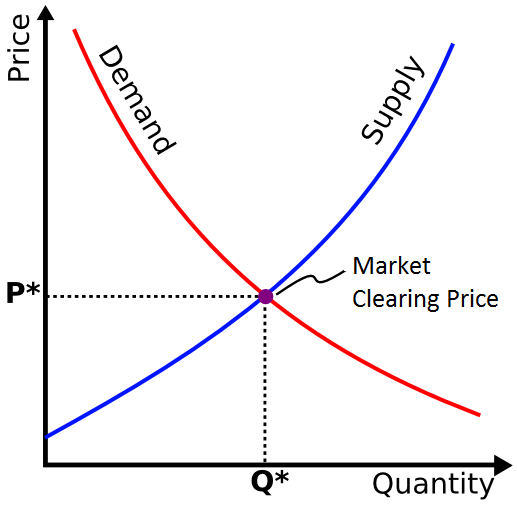

Now imagine that you took every single person and every single company and added up these decisions. So, you could ask yourself, at $15/hour how many people would choose to work at that job. How many people would choose to work at $14/hour, $13 all the way down to $0. This is called the supply curve, because it is, in total, how much labor people are willing to offer depending on how much they will be paid.

Then imagine we do the same thing with companies. How many workers will the companies want to hire if the price is set at $5, $6, $100? Keep in mind each company has different tradeoff points. Some might make a huge added benefit for each worker, and still be willing to hire someone at $100/hour and others might only be willing to pay if it cost $3/hour because the work doesn’t add much to the company’s profit. The demand is made by counting up all the positions that every company would offer at each price.

These two amounts create supply and demand curves. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Supply_and_demand

Where they intersect is called the “market clearing price”. This is the price where the amount of people who want to work equals the amount of people who companies want to [hire]. This is also the point, most economists argue, that a wage will naturally rest at without outside interference.

What this means, then, is that if someone is not making very much money, it’s either because (A) their position just isn’t one that adds all that much to the employer’s bottom line, so the employer literally can’t raise their wage beyond a certain level without losing money, or (B) their position does create a good amount of value, but the employer knows that a high wage isn’t necessary to retain them in the job. The latter case can happen when, for instance, the job is one of those mentioned earlier that has a lot of inherent appeal (and a large pool of workers who’d be willing and able to do it), so the pay doesn’t need to be particularly high to convince someone to do it. (It can also happen when the company has monopsony hiring power, which we’ll discuss later.) But the former case – where the worker just isn’t able to create much value for the company in the first place – is more common. If a worker doesn’t really have much in the way of education or training or specialized skills, they probably won’t be able to increase an employer’s earnings by all that much – and because of that disadvantage, their options for employment in general will consequently be limited; so their “minimum amount that would make a job preferable to the other available alternatives” will be lower, because they won’t have as many available alternatives in the first place. And they’ll ultimately make less money as a result.